Honors course explores how zines fostered communities of resistance

“Technology serves to institute new, more effective, and more pleasant forms of social control and social cohesion.”

—Herbert Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man

In the aftermath of World War II, social critics in the United States grew increasingly pessimistic about the roles of mass media, consumerism, and bureaucracy in society, viewing them as instruments of authoritarian control. These counterculture voices frame the curriculum of Underground Networks, a new course offered through the Honors College that examines radical forms of social life that emerge within yet in opposition to oppressive institutions.

Published in 1964, One-Dimensional Man became a seminal text for the ensuing decade of political change. In it, philosopher Herbert Marcuse rails against the trappings of capitalism and the pitfalls of a conformist society. Although it was written decades before they were born, the thoughts presented in the text are still relevant to students today.

“Reading about the one-dimensionality of society was really eye-opening,” says Emily Yoquelet, a junior majoring in studio arts and philosophy. “We produce things by and for consumer culture. It’s inescapable, but you can work within the arts to counteract a lot of the oppressions of society.”

“You can work within the arts to counteract a lot of the oppressions of society.”

—Emily Yoquelet

The students studied advertising campaigns from the 1950s and ’60s to research how products that were in short supply during the war, such as refrigerators, automobiles, and appliances, were mass-marketed to consumers in the post-war boom.

“In the 1950s, everyday life was regimented by technical apparatus. There was no private space,” says J. Peter Moore, postdoctoral teaching fellow and creator of the Underground Networks course. “The ethos of conformity and convenience created a culture of repression. Setting that as the stage, we explored the radical thought that came out of that experience and the role small, independent presses played in fostering communities of resistance.”

The rise of alternative news media, the proliferation of avant-garde poetry, and the production of feminist zines — small-circulation, self-published magazines — were all means of distributing grassroots ideas. “It wasn’t just about circulation but codification,” Moore says. “It was a means of building communities around artistic production and political ideologies.”

On a field trip to the Purdue University Archives and Special Collections, students reviewed zines circulated on campus in decades past. “I was fascinated that busy students took the time to create these unofficial documents that held a lot of meaning for them,” says Jacqueline Malayter, a sophomore majoring in electrical engineering. “It made me question why this practice stopped. A lot of these publications were banned from campus. These voices were shut down.”

After learning about different aspects of the subculture, students channeled their research into creating their own underground texts. Chosen topics included veganism, contemporary social crises, media coverage of politics, and the culture of science.

“These are not meant to be scholarly papers,” says Moore. “This project centers around personal manifestos. Students in this course are challenged to express themselves enthusiastically in these raw materials.”

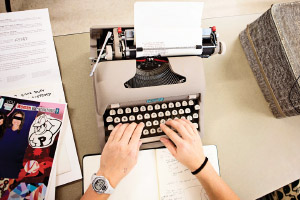

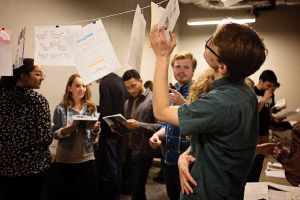

The Honors College STEAM Lab, a makerspace devoted to hands-on, project-based learning, is equipped with a vintage letterpress, 1950s-era typewriter, and a mimeograph so students can use the same modes of technology to produce their own work that were available to their mid-century counterparts. At the end of the semester, the students staged an invitation-only pop-up exhibit wedged into a basement corner of the Honors College, accessible by freight elevator. Planning a selective-access event in a hard-to-find location was inspired by the underground’s history of surreptitious operations. About 30 guests participated in the interactive exhibit.

A former beekeeper, Yoquelet chose to construct her final project in a brood box. Each frame holds a collage of made and found materials on various topics relating to the hive mind of society. “There’s no one message,” says Yoquelet. “That’s what’s cool about it. It’s open to interpretation.”

In her zine, Rage Against the STEAM Machine, Malayter examines the societal pressure to follow a prescriptive life. “This class made me reevaluate why I’m learning, what I’m learning, and why we go to school,” she says. “It’s important for people to step back and realize that education is not just learning complex math equations, but learning about society and how the world works. From now on, I’ll be more vigilant about who I am living this life for.”

The final exhibit exceeded Moore’s expectations for the initial class. “The students really took ownership,” he says. “I admire the intensity of attention they paid the work. They are gaining voice out of this process. I hope they will continue these projects outside of the class. That’s the joy of project-based learning.”