From the honey-inspired to the technically inclined, these Purdue alumni are building businesses in their own likenesses.

Given a couple of the strong suits of their alma mater, it’s not surprising that of all the former Boilermakers flexing innovative muscles in the marketplace, many earned degrees in science or engineering. Indeed, five of the six entrepreneurs sharing their success stories here have turned passions for STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) into thriving startup businesses.

Yet for every six startups that go green (in the money sense), surely 600 times that number turn belly-up. So what’s separating these CEOs from the herd you’ve never heard of? From the mouths of these bosses pour words and phrases like curiosity, tenacity, creativity, even luck. And whether these Purdue alums know their way around a motherboard, have minds for a variety of designs, or simply brought something new to market, you could bet they all get up pretty early in the morning. They might also arrive at work eager to explore the possibilities of the unknown.

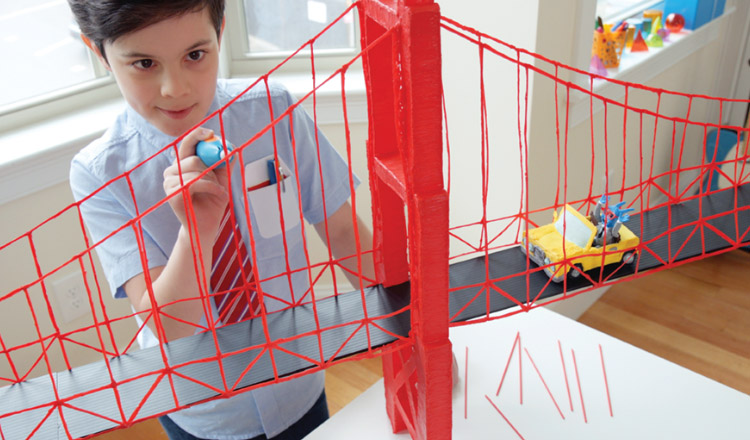

Inventing the 3-D pen industry

Alumnus: Max Bogue (S’04)

Creative Space: New York City

Invention: 3Doodler, a 3-D pen used by professionals, hobbyists, teachers, and kids

Claim to Fame: In three Kickstarter campaigns for 3Doodler, his company, WobbleWorks, raised more than $4 million.

Teamwork Philosophy (in a phrase): Dog days

Meaning: “Anyone can bring a dog to work in my company,” Bogue says. “They just have to get along.” The dogs, that is.

On Staying Grounded: “No one has a corner office here. We all work together, and even as a CEO, I do shows and in-store demos.”

Though necessity may be the mother of invention, Max Bogue’s father may have steered him to it. From disassembled parts all over their basement, the younger Bogue and his brother built machines that ran well enough for his father to drum up some business for them. “My brother and I formed a company that built and sold nearly 300 computers to hedge fund and money managers,” Bogue says. “The kicker came when a currency trader pulled my brother out of middle school one day to deal with a computer crash in downtown Boston.”

With their frequent purchases of motherboards, cases, and monitors, the youthful duo sometimes stunned the computer components reps. Ironically, the early access to the adult world may have prepared him to be an inventor of kids’ toys. “You can be an inventor, build a prototype for sure,” he says. “But you have to bring it to market and present it to people. Those are very different realms, but you need to do both.”

Bogue combined the building and presentation skills well throughout his early career. But a happy accident may have accounted for the discovery of the 3-D pen. “We were building a robotic dinosaur for a client to consider when Peter Dilworth [one of his partners] wondered about removing the nozzle head from a 3-D printer to fill in a missing layer,” Bogue says. “We spent some time Googling it because we couldn’t believe no one had done it. Then we effectively built the first 3-D pen.”

Six iterations of the 3-D pen followed, as did a manufacturers search, a business plan, and the famed Kickstarter campaigns. The 3Doodler’s key design elements include a cooling element for the extruding plastic, allowing the user to create desired shapes. Often referred to as a glue gun for 3-D printing, it quickly landed in the hands of artists, professional woodworkers, and plumbers, as well as the enthusiasts of the emerging technology.

Fast forward a few more years, and the 3Doodler has three models — Start, Create, and Pro — and more than $20 million in revenue. Bogue says he never dreamed the impact the pen could have on the world, which has led to a reference on The Simpsons, as well as partnerships with 20th Century Fox, CBS, and the Cartoon Network to create limited-edition pen sets.

One of the most gratifying things for Bogue, however, is the applications in education, including the creation of tactile maps that can allow for better understanding among blind students.

Simplifying spinal taps

Alumna: Jessica Traver (ME’14 MS ME’17)

Creative Space: Houston

Invention: IntuiTap, a medical innovation that’s addressing the pain and frustrations of spinal tap procedures through a digital, hand-held device

Claim to Fame: In 2017, Traver was named to the Forbes “30 under 30” list for healthcare for her company’s breakthrough discovery.

Work Strategy (in a word): Energized

Meaning: “I want to keep working on exciting projects, specifically ones that can impact people’s lives in a positive way.”

On Purdue Prep: “Engineering at Purdue is tough. If you can get through that, you can pretty much tackle anything. It teaches you a mental toughness that I believe is rare in the workforce, that really allows you to persevere through challenges and attack complex problems head on.”

When you think “spinal tap,” what comes to mind? Not Rob Reiner’s great mockumentary from 1984. Think lumbar puncture or epidural. Did it make you wince? Enter Jessica Traver, a 20-something Purdue engineer looking to alleviate pain from both patients and those tasked with putting needles in between lower vertebrae.

Sometimes an age-old problem, even one relying on a 100-year-old technique, can have an elegant solution. Traver developed a hand-held device that digitally indicates the precise spot to insert the needle. “It’s like a stud finder for the spine,” she says. “With all the technology available to us, it’s time we improved the procedure.”

Traver first discovered the severity of the spinal tap problem in a coveted fellowship at the Texas Medical Center in Houston, where the procedure can have some mixed results. Research shows that 20 to 70 percent of patients suffer debilitating post lumbar puncture headaches, and of those, only 15 to 30 percent return for treatment. In addition to the patient pain is the frustration imposed on doctors from imprecise procedures and the potential for emergency room bottlenecks.

“We spent four months rotating into the hospitals, just being eyes and ears and looking for inefficiencies or complications,” Traver says. “While watching these procedures, I kept asking, ‘Why are we not doing this in a different way?’ And they answered, ‘This is how we’ve been taught.’ So we began looking for new solutions and testing different technologies to see what worked best.”

The hand-held device Traver and her team developed is distinguished by its advanced pressure sensors and a digital screen that shows physicians the exact location of the vertebrae. For Traver, the project combined her passion for both mechanical and biomedical engineering, something she explored in the labs of Purdue. It also led to the startup space at JLabs@TMC, where she became the CEO of IntuiTap Medical.

“Being a startup CEO is crazy,” says Traver, now 26. “I’m responsible for my team, for the money that’s coming in from investors, and for the physicians and patients who might be affected by the device. There’s a lot of pressure. But it’s been an amazing experience just figuring out what it takes to bring something from a simple design into the marketplace.”

Coming of age as an entrepreneur

Alumnus: EJ Williams (ECE’15)

Creative Space: Dallas

Invention: Radical MOOV, a sporty hoverboard that’s reshaping the electric rideable industry

Claim to Fame: Williams was handpicked by Mark Cuban to develop what’s been called the “Ferrari of hoverboards.”

Career Outlook (in a word): Lucky

Meaning: “I was lucky to discover my passion for electric vehicles early in high school,” Williams says. “I’m also fortunate that my passion can be a career.”

On Purdue Prep: “Purdue does a great job of providing students the opportunity to pursue their own projects and ideas. They have generous funding, smart people, and valuable resources.”

EJ Williams’ pull to Purdue happened early in his Zionsville High School days in Zionsville, Indiana, after a Purdue student left him an electronic go-kart to mess around with. “I got my hands dirty maintaining it, riding it in the local parade, and teaching younger students how to build and ride it,” he says. “Those were also the beginnings of Purdue’s EV Grand Prix, which started in 2010. Then in my senior year of high school, I got a grant to build a homemade Segway, which turned out to be quite similar to the hoverboard.”

That may have also been the start of a fortunate series of events, including a summer internship at Tesla, that would lead him to Dallas and the carte blanche developmental space provided by entrepreneur, entertainer, and Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban (a longtime family friend). Cuban’s support, which includes a team of accountants and lawyers, allowed Williams and his team to focus on product development.

So what’s the radical difference in this hoverboard? “Ours is the first to have a solid platform, which means there’s no swivel in the middle,” Williams says. “It’s more of a sporty ride, kind of like rollerblading. There’s also a handle in the middle of the platform, so you can carry it, and it allows for interchangeable decks while providing a sleeker design.”

Additionally, the “torsion turn technology” and the advanced sensor controls offer riders more stability, Williams says. “It relies on weight-based steering, rather than twisting your feet, allowing for a more natural and fluid ride.”

The hoverboard preorders (starting around $1,200) began shipping early in 2018. Williams plans to ramp up sales slowly. “We would rather be involved with 100 customers and hear their feedback than simply ship 3,000 out there,” he says. “We have that option with Mark at the table — to grow slowly and make sure our customers are happy.”

As for being one of the guys in charge (along with Nick Fragnito, a Georgia Tech engineer) at the ripe old age of 25, Williams embraces the responsibility. “The most challenging thing within innovation may be deciding what needs to be done,” he says. “The entire time you’re executing a plan, you’re always thinking back to phase one, wondering if this is the right direction.”

Regardless of the outcome where he ends up, Williams seems to be enjoying the ride.

Crafting buzzworthy beverages

Alumna: Casey (Chenoweth) Jackson (MBA’16)

Creative Space: Suffolk, Virginia

Business: Wit & Mettle Meads, a quality mead maker that preserves the distinct flavors of pure honey and naturally sourced ingredients

Catching a Wave:With microbrews leading to a fermentation craze, alcoholic mead drinks could be all the rage.

Leadership Style (in a word): Mettle

Meaning: Attributable to the work ethic, spunky stubbornness, and courageousness that propelled Jackson through the US Marines (she’s still in the Reserves) and a business launch.

On Purdue Prep: “I went to Purdue thinking I needed the piece of paper, something to get a good corporate job. I’m surprised at how much I learned in a humbling and challenging experience.”

Casey Jackson believes wholeheartedly that some of the best ideas are born in a bar. For the former bartender who served many drinks in her undergraduate days at George Washington University in Washington, DC, perhaps her best idea came on a date with her future husband, Michael, in 2013. Her first taste of mead (think Viking wine) in Portsmouth, Virginia, would lead to Wit & Mettle Meads but remained a back burner dream for a while.

Never one to sit still, Jackson, who grew up near the Quad Cities in northwest Illinois, left DC without pursuing the political career she once considered. Instead, she served her country through two tours in Afghanistan as a US marine. She landed back in the Midwest in 2014, enrolling in the Krannert Executive MBA program while working as a marine recruiter. There, in a marketing class cohort, she researched and pitched a business plan for a mead-making company. “That was really the birth of it,” Jackson says. “Throughout my MBA program, I took our research and invested about a year and a half of planning through the entrepreneurship model.”

Back in Virginia after graduation, Jackson sought to perfect a mead recipe with its pure honey focus — a recipe enhanced by her eventual business partnership with Zeb Johnston, a beekeeper and craftsman. They knew their way around bees (Jackson’s father has 15 hives in Illinois), so connecting with the drinking public was critical. Along with a mead fermentation wave, they hoped to tap into a growing taste for pure honey.

“I was into beekeeping before I ever thought about making it into alcohol,” she says. “We’re very strict at our meadery about only using pure, unfiltered honey. People taste mead and realize this is a dry, beautiful version of something healthier than wine, healthier than any alcoholic beverage in the market.”

Through website sales and about 70 stores around Virginia, the mead quickly ran out of stock in 2017. “Now we’re trying to get our costs down and make our meads more available to customers,” Jackson says. “We’re quadrupling production in 2018.”

Mixing up a sweet family secret

Alumna: Aisha Ceballos-Crump (EnE’99)

Creative Space: Chicago

Business: Honey Baby Naturals, beauty and health care products

Claim to Fame: Ceballos-Crump’s company is the first Latina-owned hair care and skin care line to be in mass retail stores.

Entrepreneurship Mindset (in a word): Risk

Meaning: “I always tell people that the biggest risk is not taking a chance.”

On Purdue Prep: “I’m a very people-oriented person who majored in interdisciplinary engineering with a focus on chemical engineering and minored in political science. At Purdue, I took classes that helped me understand what I wanted to do.”

A first-generation college graduate, Aisha Ceballos-Crump learned much from two sets of grandparents, all of whom came from Puerto Rico to work in the steel mills of Gary, Indiana. She attended high school at Emerson School for the Visual and Performing Arts, where she majored in drama, leading to dreams of going to New York University to become an actress. Instead, the valedictorian stayed closer to home, intent on parlaying a chemical engineering degree into good money.

A self-described “unique left brain, right brain” student, Ceballos-Crump found the interdisciplinary engineering more fitting with her creative and adventurous spirit. She landed a good sales job at Eli Lilly, then another where she learned the beauty business — the latter part of a 10-year plan to “merge the performance of being in front of people with the science of creating.”

After manufacturing her honey-based product (a secret ingredient in her grandmother’s beauty regimen), Ceballos-Crump made the leap of faith by launching her brand, Honey Baby Naturals. “In my heart and soul, I knew that I had something that could improve people’s lives while creating generational wealth for my family,” she says. “But the struggle was real. The first couple of years, we didn’t make any money. Every dime went back into the company. A lot of people give up in that first year, and it can be a real financial strain, especially as a mother of three.”

Yet Honey Baby Naturals seems built around a three-generation multicultural family, including the nod to her grandmother and the current role her husband and children play. “Our tagline is hydrate, heal, and protect,” Ceballos-Crump says. “The core foundation is about healthy hair and skin products for the entire family.”

Ceballos-Crump largely connected with customers through social media marketing and direct consumer events on frequent trips from Chicago to Philadelphia, Atlanta, New Orleans, and Washington, DC. As sales and distribution increased, Honey Baby Naturals soon landed in more than 400 retail stores, including Target and Meijer. In 2018, the brand is expanding to 1,600 locations, including Sally Beauty, Walmart, RiteAid, and CVS.

As proud as she is of her own achievements, Ceballos-Crump is an oft-requested spokesperson for STEM outreach efforts. “There’s great disparity between males and females in technology fields,” she says. “I want to encourage young women and minorities to explore entrepreneurship opportunities in chemistry, technology, and beauty.”

Going Gaga over a round piano

Alumnus: David T. Starkey (ECE’77)

Creative Space: La Jolla, California

Invention: PianoArc, a circular keyboard with 288 keys that boosts the stage presence of piano players

Claim to Fame: After traveling around the world on a Lady Gaga tour, the PianoArc appeared with the Mother Monster at the Super Bowl LI (that’s 51!) halftime show on February 5, 2017.

Innovation Mindset (in a word): Tenacity

Meaning: “You’ve got to stay at it or it’s not going to happen.”

On Purdue prep: “The Purdue education was very good. I came out and I could produce — a useful electrical engineer right out of the box.”

You might call David Starkey the guy that another guy knew. As he tells it, Brockett Parsons, the keyboardist for Lady Gaga, was brainstorming (in whatever form that takes) late one night with some fellow musicians. Someone said, “Hey Brockett, you’ve got to bring your game up, man. Make it more visible.”

A musician himself, Starkey understood the dilemma. Of everyone on stage, without the swirling arms of a drummer or the lead guitarist’s prancing and back-arching solos, a piano player can seem a bit stodgy. “Like he’s just sitting there typing,” says Starkey, who made a name for himself in the industry with various enhancements to electronic keyboards.

Starkey first came on board after a piano technician used a band saw to build a somewhat monstrous version of a round piano that weighed 900 pounds. “After we sold two of them, that’s when the engineer in me said, ‘No more. We’re not going to do it this way. We’re going to redesign it with a proper mechanical design.’”

Within that redesign, Starkey insisted on no plywood, drywall screws, wood putty, or hand wiring. Driven by custom software and circuit boards, a second iteration of the piano won a 2015 Edison Gold Award as a best new product in media and visual communications. In a third design, the foldable piano, called PianoArc, weighed in at 120 pounds and maintained 288 continuous keys.

Though its appearance in the Lady Gaga halftime show during Super Bowl 2017 brought a surge of traffic that crashed the PianoArc website, the “exotic keyboard” now known as the Brock360 hasn’t become a living room standard. Custom built and selling for $60,000, there’s not much demand in a market where a very expensive keyboard costs $3,000, Starkey says.

After the Super Bowl splash, it was back to the drawing — or in Starkey’s case, circuit — board. In a 40-year career distinguished by 15 patents in musical instrument digital interface (MIDI) technologies, he’s got a knack for enhancement. “MIDI is the language interface that connects synthesizers together or a keyboard to a computer for recording and playback purposes.”

Whenever he hits playback on his life, Starkey can reflect on all sorts of combinations — music and MIDI, artistic form and function, and, of course, endless trial and error. The Chicago suburbs of his youth, where he spent nearly two years working at a guitar amplifier factory, and his path through Purdue’s electrical engineering (then pre-computer) program resides in the rearview mirror. Yet they proved critical on his Super Bowl run.