Prior to the beginning of October, Paul Chestovich (ChE’02, A’02) thought the most memorable case he’d seen was a man with a two-by-four piece of wood impaled in his chest. But after October 1, that all changed. Late that night, he and his level I trauma staff at the University Medical Center of Southern Nevada in Las Vegas treated injured concertgoers from the Route 91 Harvest music festival shooting massacre that left 59 people dead and more than 500 injured. “We saw gunshot wounds all over the bodies,” Chestovich says. “People were everywhere; the noise level was high.”

An outsider might’ve called it chaos, pandemonium, or bedlam. Doctors, families, friends, nurses, surgeons, and security populated the trauma center waiting for injured patients. On a typical busy Friday or Saturday night, Chestovich, assistant professor and associate program director of surgical critical care for the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, School of Medicine, might treat 10 to 15 people. But on October 1, hospital staff treated more than 100 patients. Some were admitted. Others had surgery or went to the ICU. Because of the large influx of traumatic injuries, patients had to be ranked according to severity, what trauma care calls triage.

With large numbers of severely injured patients, trauma providers triage patients starting with those where time is of the essence. “With a wound to the head, neck, or torso, patients are triaged higher because these injuries are life-threatening,” Chestovich says. Other patients with leg or arm injuries are triaged lower because they’re easier to manage and stop the bleeding.

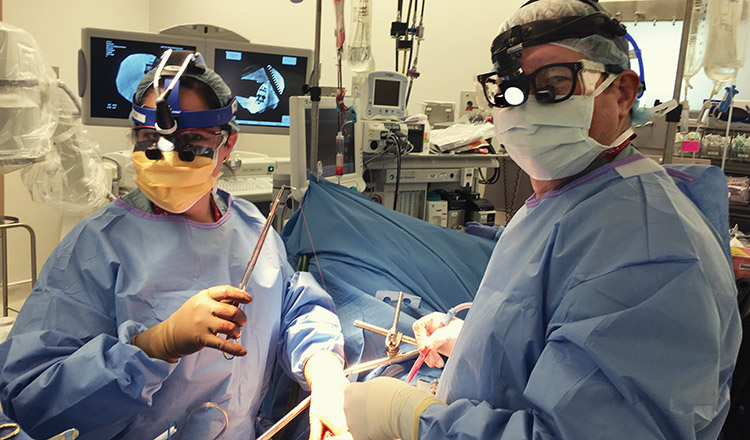

That night, Chestovich and his team saw people coming in with gunshots to the head, neck, and torso and patients who were injured by shrapnel or the general melee. “We were treating people who had injuries that could kill them very quickly, so we had to try and reverse that as fast as possible,” he says. “The minute they hit the bed, we started assessing them to see what needed to be fixed.” This is where Chestovich found that his Purdue engineering training came in handy, helping him systematically identify a patient’s physiology then evaluate and assign priority.

“To treat 100 patients in one night is incredible.”

Into the night, they operated on a dozen patients, placed central lines and chest tubes, and performed angiographic embolization and resuscitations. “In trauma care, we help patients get through really bad days, maybe even their worst days,” Chestovich says. Though his team couldn’t fix every injury, they did fix many — something he finds very satisfying. “That night, I saw tremendous examples of strength and perseverance by our health care providers. To treat 100 patients in one night is incredible.” Still, Chestovich emphasizes, “we do this every day — it’s just what we do.”