Alumnae fondly remember their time as student stewardesses during the golden age of flight

It would be a few more years before Frank Sinatra crooned, “Come fly with me, we’ll fly, we’ll fly away,” but in the early to mid-1950s, the romance of flight had already won the hearts of Purdue students who signed on to become stewardesses with the University’s own airline.

It was an era when commercial flying was glamorous, when pilots and stewardesses in crisp uniforms took passengers “up where the air is rarefied” and served them full meals with drinks. Airplane seats were wide and spaced far enough apart that passengers could stretch their legs and nap while gliding at more than 200 miles per hour instead of stumbling along at 50 on the ground in a Chevy coupe.

The Purdue Aeronautics Corporation was created in 1942 to advance aeronautical engineering on campus and promote use of the airport — the first university airport in the nation. It didn’t take much effort to keep the airport busy during the war. The late Purdue professor and engineering historian HB Knoll said, “During the war, the airport became a training center, and planes buzzed around it like bees around a hive.”

When the war ended in 1945, Purdue launched a program in air transportation in its new School of Aeronautics which had been split from mechanical engineering. Air transportation trained students in a variety of areas linked to commercial flight. Looking for revenue to support the program and the airport as well as a way to teach students, the Purdue Research Foundation bought an airline, Midwest out of Omaha, Nebraska, in 1951. Purdue planned to operate the airline with professional employees and student interns. Paying customers would provide revenue for the University’s flight programs.

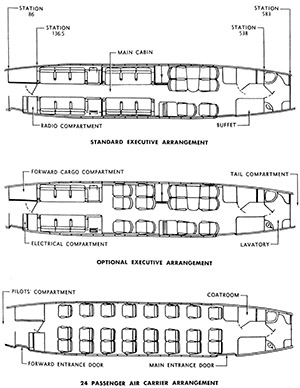

The federal Civil Aeronautics Board rejected that plan but approved a Purdue Aeronautics proposal to operate a DC-3 charter service out of the University’s airport — the only one granted in the Midwest. PRF loaned money for the purchase of DC-3s, twin engine planes that seated 24 passengers and flew about 200 miles per hour.

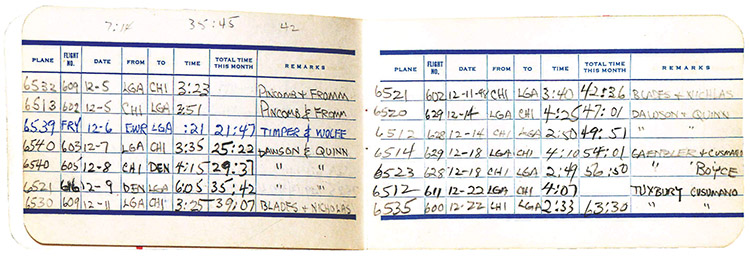

Called Purdue Airlines, the charter service began in 1953 flying Big Ten and other universities’ athletic teams to games and back. Purdue Airlines eventually also flew professional teams, and a ballet company, and did beer promotions in Michigan. For a time, it even flew Hugh Hefner’s Playboy jet. Financial difficulties drove the airline out of business in 1971.

Purdue Airlines used professional pilots, and while students in the air transportation program did much of the work, even flying as copilots, they needed stewardesses. So Purdue Airlines put advertisements on campus bulletin boards and in the Exponent. They had no trouble finding interested young women at a time when working as a stewardess was a very glamorous job.

It was an era when airplanes could take you on exotic vacations or just to the places you needed to be, and whatever the destination, the journey was relaxing, exciting, and even a little adventurous. It’s no surprise, then, that women like Judi Barney Kless (LA’57) were attracted to flying on Purdue’s fleet of DC-3 airplanes. And if they got to meet lots of Big Ten athletes and a few celebrities — well, no one was complaining. Of course, the Purdue student stewardesses didn’t get paid. But who would dream of getting paid for having so much fun.

Kless came to Purdue from Indianapolis to study home economics. She didn’t like it and transferred to the School of Science, where she majored in interior design. In 1956, she saw the ad recruiting stewardesses. At the time, women could not wear slacks on the Purdue campus outside of their residence hall. But with no training, no experience, no insurance, and no need to even tell their parents, they could become airlines stewardesses and visit exotic places like Ann Arbor, Michigan, and Iowa City, Iowa.

“Purdue Airlines flew a lot of the Big Ten athletic teams and a group of us girls thought how fun it would be to be stewardesses on those planes with those neat athletes,” Kless says. Kless was one of two members of Kappa Alpha Theta Sorority who signed up.

It was mostly weekend work, and many of the trips were there and back in one day. The stewardesses didn’t get uniforms, but Kless dressed in a white blouse, navy skirt, and matching blazer that looked like one.

“It was so easy,” she says. “All we did was stand at the door and greet these guys when they came on the plane, and when we were in the air we passed out box meals, drinks, and magazines. It was great fun. The guys were wonderful.”

They flew more than athletes. Kless once was on a flight with Elliott Roosevelt, son of the late President Franklin Roosevelt. She also got to know Purdue President Frederick L. Hovde, a frequent passenger as he flew to various speaking events and meetings.

On one trip, Kless flew to Champaign, Illinois, to pick up the University of Illinois basketball team. She flew them to West Lafayette for a game against the Boilermakers, and she arranged for all the players to have dates that night with her sorority sisters.

“It was glamorous,” Kless says. “It was more of a lark than anything else.” She was busy with other activities on campus and eventually stopped flying. Among her other activities, Kless was elected Air Force Queen and given title of Honorary Colonel, Air Force ROTC.

Peggy (Noland) Lipinski (HHS’56) took the first airplane flight of her life as a stewardess for Purdue Airlines. She came to West Lafayette from nearby Kokomo, Indiana. Lipinski saw an advertisement for the job on a bulletin board and just decided to try it. She had always been a little adventurous, and the next thing she knew she was a stewardess taking Big Ten teams around the Midwest.

“They were very nice young men, and they actually took care of me rather than me taking care of them,” Lipinski says. “I took whatever trips I could fit into my schedule. It wasn’t work. It was fun. I love football, and I got to stand on the sideline with the team during the games.”

“They were very nice young men and they actually took care of me rather than me taking care of them. It wasn’t work. It was fun.”

— Peggy (Noland) Lipinski (HHS’56)

On that first flight, she remembered that she had forgotten to tell her parents about her stewardess job. She eventually did tell them — when she was no longer doing it. “They just kind of looked at me like they were saying ‘That’s our daughter,’” she says.

She got to know the Big Ten teams and their favorite card games. “The Illinois guys were always in suits and they played bridge,” she said. “The Iowa guys played pinochle and another team we took from Ohio played euchre.”

One trip didn’t go well. The pilots were having an ice problem. On a flight back to Purdue one evening after dropping off the athletes, Lipinski was seated alone at the back of the plane when the pilots called her forward to the cockpit.

“The pilot said they were having some trouble and they couldn’t land at Purdue, they had to go to Indianapolis,” she says. “They had the equipment there that was needed to take care of us. I stayed in the cockpit for the rest of the flight. At one point we were headed for a radio tower, but got out of that. “The pilot was very calm. The co-pilot was not. I was in better shape than he was. He was panicking and we were trying to calm him down.”

When they reached the Indianapolis airport, the runway had been cleared for them and emergency vehicles were ready to respond. The cockpit windshield iced up and the pilot decided to stick his hand out a side window and scraped it off. He was afraid he might lose his wedding ring in the process, so he took it off and handed it to Lipinski.

They landed successfully, but halfway off the runway. The three spent the night in Indianapolis and Lipinski was sent back to Purdue in the morning on a bus.

Though Lipinski remained calm during the emergency, it was an emotional experience and it caused her to rethink her life. Not long before the flight, she had broken up with her boyfriend. She thought he was getting too serious.

Maybe it was the realization that life is short and anything can happen. Maybe it was holding the pilot’s wedding ring and realizing how much it meant to him. Whatever compelled her, when Lipinski returned from the flight, she contacted her boyfriend, Dwayne (A’58). They got back together, married, and had a wonderful life. Lipinski told her children the story of how their parents got back together. “They thought it was romantic,” she says.

Barbara McCabe Jarecky (AAE’57) graduated in the air transportation program that was part of Purdue Aeronautics. Jarecky wanted to fly and enrolled at Purdue because of its air transportation program. She earned her pilot’s license as an undergraduate.

Jarecky remembers only one other woman in her air transportation class, but she says she felt discrimination only once. “I was never picked on,” she says. “A lot of my classmates were Korean War veterans on the GI Bill. Some of them were married and had families. One time, one of my professors, a law professor, started in on me and one of my classmates walked up to the front of the room and grabbed this guy by his tie. He said, ‘If you pick on her, you’ll have to answer to me.’” She had no more problems.

When she learned Purdue Airlines was looking for stewardesses, she thought that would be a natural fit.

“They would pick me up by car at the dorm and take me to the plane,” Jarecky says. “I would monitor the cabin. We flew all over the Midwest.”

She had no interest in getting to know the passengers. She was more interested in the airplane. “Meeting guys at Purdue was no problem,” she says. “Listen, when I was a student, there were 12,000 undergraduates and 2,000 of them were women and 10,000 were men. Trust me. Getting a date was no problem. And I never dated anyone in my class, always older.”

The big payoff for Jarecky was when the airplane was “dead-heading” back to the Purdue Airport without any passengers. She had her pilot’s license, so the pilots would allow her to fly the DC-3 and they signed her logbook. “I have a few hours in the cockpit of a DC-3,” she says.

The years Jarecky, Lipinski, and Kless were students turned out to be among the most significant in the University’s long aviation history. They were students at the same time as three men who would become part of flight and space history — Neil Armstrong (AAE’55, HDR E’70), and Gene Cernan (ECE’56, E’70), who became the first and last men on the moon, and Roger Chaffee (AAE’57), who also became an astronaut.

Kless and Jarecky knew these men who would soon fly into space, but they didn’t realize how soon the exploration of space would begin. Only dedicated fans of science fiction were familiar with the word “astronaut.” The first NASA Mercury Seven astronauts, including Purdue graduate Virgil “Gus” Grissom (ME’50) were named in 1959.

Since then, three Purdue alumnae have become astronauts. But in those mid-1950s days, when air travel was glamorous, a chance to fly athletic teams and famous people around the country as a stewardess put you on top of the world.

John Norberg is a freelance writer and author of eight books about Purdue and its alumni including Wings of Our Dreams: Purdue in Flight.