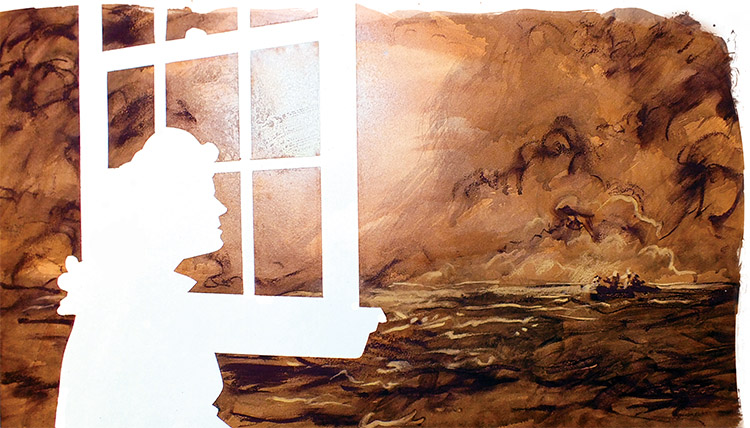

How a Purdue PhD student wound up floating on a wooden raft for several months during World War II — and what happened to the alumna he left behind.

They’d been floating on a wooden raft in the South Atlantic Ocean for almost three weeks, surviving on canned milk, crackers, and tiny chocolate squares. Their skin was stripped raw from sunburn. Their feet were covered in bloody sores. They were shedding weight, hungry all the time. And now, after 16 days, their meager supplies had run out.

The five men needed food.

Ensign James Show Maddox, a PhD student and instructor, had been their now-sunken ship’s gunnery officer. He still served as the group’s de facto leader — and he was desperate enough to try something crazy. Sharks had buzzed by the men ever since they leapt into the sea to escape their torpedoed ship. What if they tried to catch one and make it dinner?

Maddox looped a rope into a lasso, dangled it in the water, and after several hours of trying, trapped a shark. He pulled the loop tight around its fins, and together, all five men hauled the creature onto their raft. They stuck a paddle in its mouth as it flailed and jerked. Eventually they flipped it over and split the shark open with a knife. As they divvied up the meat, Maddox asked for the shark’s heart.

It’s doubtful that any of his Purdue classmates or students would have recognized 29-year-old Maddox in that moment — a bloody shark heart pumping in his hand, then entering his mouth. But it was indeed the same Maddox who taught public speaking at the West Lafayette campus. The Maddox who married Patricia Heine (S’40) in 1941 and then, facing a national draft, joined the navy.

The Maddox who, from late 1942 until early 1943, spent more than two months drifting across the South Atlantic on a raft with two other American sailors and two Dutch merchant mariners, doing things people never imagine themselves capable of until their lives depend on it.

Before the Shark

Long before he held a still-beating shark heart in his palm — and then his stomach — James Maddox was a well-liked kid in Fairmont, West Virginia. He was elected secretary of his senior class and acted in school plays. Below his senior photo in the yearbook, the caption reads: “The ladies call him sweet.”

Maddox’s parents encouraged higher education, and he graduated from West Virginia University in 1935 with a degree in public speaking. After earning a master’s in speech pathology from the University of Iowa two years later, he enrolled in Purdue’s applied psychology doctoral program in 1937.

At first he worked as a resident adviser in Cary Hall to help pay for his education, but eventually Maddox became a full-time instructor in the speech department. He supervised the corrective speech labs and published research on stuttering. He’d found a home in academia — and his actual home was falling into place, too. Maddox met Patricia Heine through the Lafayette Little Theatre, and they were married in 1941.

But in those same years, with World War II well underway, the US draft had returned. Maddox applied for naval reserve officers’ training and pitched himself to work as a Navy psychologist. The navy turned him down, saying he didn’t have enough experience.

Instead Maddox became an ensign — the navy’s version of an entry-level commissioned officer — and he left for training in the spring of 1942. Rather than working in the medical corps as he’d hoped, he was put in charge of crews in the US Navy Armed Guard.

By the fall, Maddox was at sea on the Zaandam, a Dutch cargo vessel that carried 110 Dutch crew members and officers, five civilians, 163 repatriated sailors rescued from sunken vessels off the coast of Africa, and 20 armed guard sailors.

The navy presence was supposed to protect the ship from enemy attacks.

Stranded at Sea

The jolt came in the late afternoon on November 2, 1942, a few hundred miles off the coast of Brazil, when a German U-boat that had already destroyed two other ships in the area smashed a torpedo through the Zaandam.

The ship’s hallways filled with water and wreckage. “Some people on the ship were hollering and screaming, scared as hell, but most of them were calm,” Basil Izzi, an American survivor of the attack and a member of Maddox’s gun crew, told the New Yorker in 1943. “The whole place had a horrible smell and it filled up with smoke.”

Then a second torpedo hit. The ship twisted and began to sink.

Many people made it off the ship, but there weren’t enough lifeboats to hold them all. Rafts had been lost, too, prematurely released when the ship was still moving after the first torpedo hit. In the water, people grabbed hold of whatever they could find — flimsy bamboo rafts, chunks of wreckage, pieces of wood.

It started to get dark outside. “You would hear guys hollering for help, screaming that sharks were attacking them, and there was nothing you could do,” Izzi told the New Yorker. “Then maybe they would stop screaming, and you wouldn’t hear them after that, or maybe a guy would stop right in the middle of a yell and you would know that something certainly got him.”

Eventually Maddox ended up on a slatted wooden raft — roughly nine feet long and eight feet wide — with the four men who would become his only company for the next several months: 19-year-old Izzi; a repatriated American sailor named George Beezley; a Zaandam crew member; and a 17-year-old Dutch merchant mariner.

In the beginning, the five men took turns keeping watch for any passing ships. At night they huddled close together. “The mornings went by quick, and the afternoons like years,” Izzi told the New Yorker. “Each day we made a notch on one of our paddles to mark the passing of time.”

After their limited rations ran out on the 16th day, and after Maddox wrangled them a shark, the men began catching birds and small fish to eat raw. Drinking water came from wringing out their shirts and sailcloth after a rain.

“This guy had a huge, huge sense of responsibility and obligation,” Alvarez, author of Forgotten Hero, says of Maddox. “The other men looked at him as their leader, and he did it in such a way that there was never any conflict. Nobody got murdered, nobody got thrown overboard, they didn’t resort to cannibalism. It was his creativity, his faith, and his leadership.”

The rainy season started during their second month floating at sea. Storms tossed and jolted the raft. The men crowded under a piece of canvas to stay dry, sometimes for days at a time, but they still got soaked and chilled. Izzi’s birthday, December 3, brought an especially hard rain.

“It rained so hard I couldn’t see more than a few feet in front of me,” he told the New Yorker, “and I cried and tears rolled out of my eyes because I knew that if a ship came by they couldn’t see us.” During their months on the raft, the men spotted three different ships. They used their limited strength to wave cloths and flags, but none of the ships seemed to notice them, and none stopped to help.

Maddox turned 30 on December 12, the group’s 40th day at sea. On Christmas Eve, he led the group in a carols sing-along.

Beezley died on day 66, and soon Maddox started to get sick, too. On day 70, his vision began failing. The group ran out of water six days later, and Maddox died on day 77 — only six days before the remaining men were rescued by an American convoy off the Brazilian coast.

The One He Left Behind

Back in Washington, DC, Maddox’s wife, Patty — already aware that her husband was missing in action — opened a telegram on March 12, 1943, that said James was “reported as having died in the performance of his duty and in the service of his country.”

But she probably knew that already. Izzi had given an interview from the hospital the day before, published in her local newspaper.

According to Alvarez’s research, Maddox was the first Purdue faculty member to die in World War II. Patty also had deep ties to the university. She graduated in 1940 with a major in science. Her father taught in the School of Pharmacy, and her brothers both went there. (In fact, the Robert E. Heine Pharmacy Building is named for her older brother who was president of Purdue’s Board of Trustees from 1979 to 1981.)

Almost a year after Maddox’s death, Patty enrolled in a special training program with the American Red Cross, designed to support soldiers in Europe. She boarded a ship to England just before Christmas. In Forgotten Hero, Alvarez writes that Patty and the other Red Cross Clubmobile volunteers made and served doughnuts and coffee daily and “were coached in ways to have friendly conversation with servicemen to bolster morale.” The women drove their truck around Europe, following American troops across France and Germany and even facing enemy attacks.

Patty returned home in 1945 and four years later married Gilbert Collins. Alvarez says the Red Cross experience had undoubtedly changed her. “If she was a young woman in the 1970s, she would have been a feminist,” he says. “Instead she gets back in the late 1940s, so she’s more of a bohemian.”

A niece, Barbara Heine Wert, remembers going to visit her Aunt Patty and Uncle Gil on their Wisconsin mink farm in the 1950s. Their house had electricity but no running water or indoor bathroom.

“She really didn’t talk about Uncle Jim at all,” Wert says. “And if anyone brought him up, she just changed the subject.”

Wert didn’t discover Maddox’s story until she was in her 40s. She and her brothers would visit their Aunt Patty on the West Coast every year — she had long since sold the mink farm and gone to work as a school secretary — and they often looked at old photographs with her. Patty also had a copy of the book 83 Days: The Survival of Seaman Izzi, written by New Yorker reporter Mark Murphy. Wert bought her own copy and in the early 2000s, learned everything her uncle had gone through.

A Story Rediscovered

Outside of the Heine family’s late discovery, Maddox’s story had been mostly forgotten by the 21st century.

But after Pamela Nussear, Raymond Alvarez’s longtime friend in Fairmont, West Virginia, asked him to research the people who had previously owned her home, he plunged himself into an eight-month quest starting in October 2015.

It turned out the house’s previous owners were James Maddox’s parents. Soon Alvarez had identified their son, figured out where he went to college, and discovered the New Yorker article series from 1943.

“I just kept finding more and more,” he remembers, “and I said, ‘We have to do something with this. People have forgotten Maddox’s remarkable story.’ And we set out to tell it.”

Alvarez landed a grant from the West Virginia Humanities Council, delivered community lectures and presentations, and raised money to put up a memorial for Maddox in Fairmont — a marble bench dedicated on Veterans Day in 2016. He also wrote and published the 48-page book Forgotten Hero. He says he’s given out more than 500 copies so far, and the book is available on Amazon and Kindle, with all proceeds going to local historic preservation projects.

“Raymond sent me at least two drafts of the book as he was writing, and each time he brought me to tears with what he said and how he said it,” Wert says. “I kept wondering what Aunt Patty’s life would have been like if [James] had lived. I certainly would have liked to know him.”

In spite of the tears, Wert says she’s “over the moon” that Alvarez resurrected her uncle’s story and filled in so many missing details. Alvarez is pleased, too. “I love to do local history projects,” he says. “You can learn so much by just looking around you.”

Molly Petrilla is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.