A trio of Purdue alumni, by coincidence, join to make the world a little brighter for kids in need

Amy O’Shea wanted to change the world.

Unbeknownst to her, all it took was the help of a couple of fellow Boilermakers to make it happen.

Back in 2009, when O’Shea (LA’09) was an undergraduate reporter at the Exponent, she was introduced to the Invisible Children movement, which sought to highlight the plight of exploited children, forced to participate in the armies of Joseph Kony in Central Africa. Drawn to this movement, O’Shea took it upon herself to visit Uganda and Arlington Academy of Hope, where she spent several months getting to know the children and the obstacles they face. She was stunned at how something like an upper respiratory infection — a minor hiccup for a child in the United States — could have such far-reaching effects, derailing children in their studies.

“It was heartbreaking to see the prevalence of upper respiratory effects in the region and to know that we have the technology to alleviate it,” O’Shea recalls.

These colds, O’Shea came to understand after research and consulting with medical professionals in Uganda, were often the result of indoor air pollution. People in these remote areas often lack access to energy. For heat and light, they rely on indoor stoves and kerosene heaters, which affect the air these children must breathe. The effects are far-reaching; the World Health Organization estimates that 4.3 million people each year die from exposure to household air pollution. O’Shea could see how access to such basic human needs as clean air and water are all interrelated with access to education and opportunities for advancement and improving their lives. Without easy access to electricity, children were often stymied and unable to complete their education, which creates a major roadblock to any sort of success.

Thus O’Shea realized she wanted to do something to help these children. And she knew she wanted it to be more than just a one-time donation; she wanted to create a movement, a mission, which would engage and educate others along the way.

Inspired, too, by the model of companies like TOMS Shoes and the give-back retail process, O’Shea wanted to sell something that could help empower people in these situations.

“I wanted to do something TOMS Shoes — buy a cool product and give back — but also make sure it’s sustainably made,” she says. She settled on journals, drawn to the beauty and naturalness of the simple bound book.

“I think there’s a big resurgence of the simplicity of pen to paper,” she says. “In this technology-driven world, people are trying to get away from screens.”

O’Shea had heard of a company called Nokero that made solar-powered lights. These lights, she realized — clean, renewable energy that could provide much-needed illumination that could help these children further their studies at night — could vastly improve the quality of life for these children. So she reached out to its founder, Steve Katsaros, to see if he’d be willing to help. Katsaros, like O’Shea, is a Purdue alumnus. But neither of them knew it at the time.

Lighting the World

Katsaros (ME’96) came up with the idea of these solar lights as a virtual lightbulb over his head one morning. He hadn’t been focusing on solving energy problems in affected areas, but somehow, the idea just dawned on him.

Such a large population in Africa and Asia lacks electricity; worldwide, up to 1.4 billion people have no — or limited — access, including people in Indonesia, India, Haiti, Mexico, Bangladesh, Cambodia, and sub-

Saharan Africa.

“We in the United States are energy illiterate,” Katsaros says. “We walk into a room, turn on a light switch and never consider where that comes from. We are in a race to use more and more energy every day.”

When O’Shea reached out to Nokero, Katsaros says it was a natural partnership. “It’s a great project,” he says. “It exposes people to our technology. We’ve spent seven thoughtful years creating inroads to distributors and programs that have sold 1.6 million lights.” Thus this expansion helps spread the word about the technology, one that is ultimately very beneficial.

Katsaros was also drawn to the idea of social enterprise — a profitable company approach to poverty reduction. He wanted to develop a self-sustaining business as opposed to the not-for-profit model. The solar lights his company has developed are now available in more than 120 countries around the world. With a lifespan of four to five years, they provide much-needed lights to communities where access to basic electricity is unreliable or simply not available at all, increasing opportunities for education, productivity, and safety in these areas.

The issue for O’Shea, then, was just how to get the lights into the communities that could use them most. Enter Elias Matar of Lighthouse Peace Initiative Corporation, whom O’Shea called on the recommendation of a friend. Matar is also a Purdue graduate, but neither of them made that connection at the time. “It was another fortuitous connection,” O’Shea says.

A Humanitarian Mission

Matar (EE’86), a Syrian American, has been following the plight of Syrian refugees over the past few years. He heard the stories and saw the footage of refugees fleeing, walking, carrying literally nothing with them.

“It was surreal,” he recalls.

He wanted to do something significant to help. He reached a breaking point when he heard coverage of 30 people, refugees from Syria, found dead in an abandoned shipping container on the side of a road. Matar bought a ticket; flew to Vienna, Austria; rented a van; filled it with water, food, and hygienic kits; and drove across three countries to reach Sid, the Serbian border with Croatia.

“It was insane — I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “My life has never been the same.”

Matar saw the Red Cross functioning out of a single tent, a single blinking light. He saw thousands of displaced people crossing borders, in a desperate plight. Able to speak Arabic, Matar found himself not just providing aid but also listening to people, letting them share stories, mostly of family and friends, loved ones who were lost, all documented in his film Flight of the Refugees.

Germany and Sweden were the only European countries taking in refugees at that time; other countries had illegal refugee camps, where people were often not treated well; some people fell into situations that evolved into human trafficking.

In June 2016, Matar went to Lebanon, which had more than 2 million Syrian refugees, all living in a state of limbo — without a country, nearly no rights, very little education, and not enough food — for the past five years. Matar was intent on creating more of a long-term commitment to children and vocational and women’s issues. Eager to help combat such problems as child labor and exploitation and girls as young as 14 being forced into marriage, he launched the Lighthouse Peace Initiative Corporation, a nongovernmental organization that embeds itself in communities at the grassroots level, working on early childhood development, education, and women’s vocational training.

“We meet each settlement and look at their needs,” he says. In creating community centers that provide a safe haven, people can work together, can create a caring community.

“I can’t reach 2 million people, but if I can reach 100,000 and collaborate with leaders, that in turn can be part of rebuilding Syria when the war is over. That’s how I can help.”

A Boilermaker Collaboration

So, these three Purdue graduates — O’Shea, Katsaros, and Matar — individually had ideas about what they could do to improve the lives of people in underserved parts of the world. O’Shea reached out to Katsaros to help procure the solar lights; she then reached out Matar to help her distribute them to the people who could use them the most.

The fact that all three were Purdue graduates? Serendipity.

“I was thrilled,’ O’Shea says. “I absolutely loved Purdue; I value my Purdue experience so much. It made me really happy to get to work with them.”

Katsaros gives O’Shea complete credit for the inspiration. “This is all Amy O’Shea,” he says. “She’s a real gem.”

The three came together by happenstance; Katsaros was already committed to the project when he found out, through a call from the Exponent, that O’Shea was a fellow Boilermaker. “I just love that here we have three Purdue alumni who somehow have the shared vision of a better world through true collaboration.”

O’Shea thoughtfully considered whether the distribution of the Nokero lights was in the best interest of the areas she intended to help — “We don’t want to hurt the local economy if there’s a guy down the street selling them” — and did a pilot program to see if they were useful. The centers that Matar was creating ended up being a perfect fit, as at night, there was absolutely no light between the tents in these camps and no market for solar lights. Thus the lights helped create an outdoor community and a place to gather.

“I am pleased to hear the kids have a place that’s safe and well-lit at night,” says O’Shea. “It adds a little comfort in their otherwise very difficult situation.”

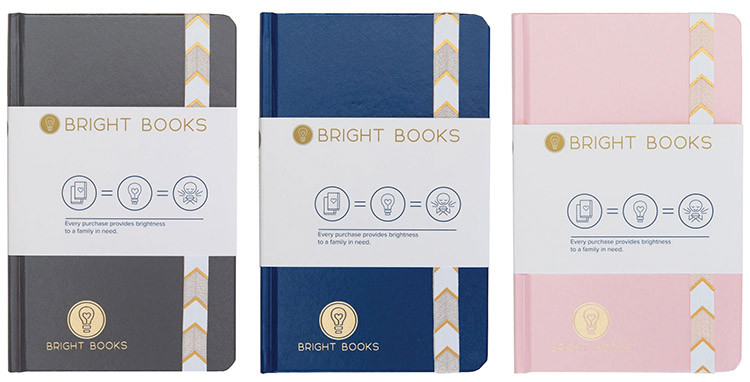

Bright Books, O’Shea’s company, launched in early 2017. The journals are selling well, O’Shea says, and the Nokero lights are in use. This is currently just a sideline for O’Shea — “my nights and weekends project,” she says — but she has dreams of expanding, making it her full-time work in a few years.

O’Shea, Katsaros, and Matar all credit their Purdue education for instilling in them a desire to help others as well as giving them the tools to make it possible.

Matar recalls a systems engineering course and the professor who taught him that engineering is not necessarily the end but rather the means.

“Electrical engineering teaches you how to learn, how to adapt, how to solve problems,” he says. “The whole humanitarian thing, I didn’t know anything, but I took some online classes and learned. My engineering degree from Purdue helped me learn and adapt, how to problem solve. I didn’t abandon engineering; I just took it in another direction.”

Changing the World

The trio has high hopes for what these lights can mean to the people in this region. Matar is working to help people out of the most dire of circumstances, helping them build a new home. Katsaros is proud to have brought them sustainable technology.

“From a personal perspective, I really feel compelled to do work that has relevancy,” he says.

And O’Shea is proud of the change she can make — change that is happening, in no small part, due to other Purdue alumni.

“This was meant to be,” O’Shea says. “These little connections make me smile.”

Cindy Gerlach is a freelance writer.