It’s easy to be cynical these days.

And yet despite the very real problems we face in our world — war, pandemics, climate change — an enormous amount of exceptionally powerful and positive work is happening across the country and around the world. We may live in challenging times, but human ingenuity remains high.

In fact, many Purdue researchers are remarkably optimistic about the potential of the work they and others are doing within their fields. For this story, we asked eight Purdue faculty members to share — in their own words — the work that they see in their fields that makes them hopeful.

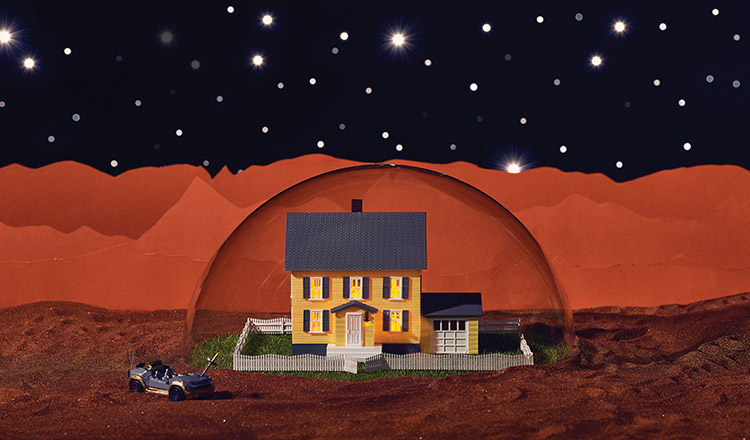

1. The push to go to Mars is revitalizing the desire to explore the universe.

Briony Horgan is an assistant professor in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences.

NASA’s Apollo program was incredibly inspirational. It put humans on the moon and brought back hundreds of kilograms of moon rocks that revolutionized our understanding of the solar system. When that program shut down in the 1970s — with very limited organization and record keeping — we lost a lot of essential knowledge that has taken decades to rebuild.

But the growth of the private space industry, including Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin, is big news. These companies are making incredible advances in reusable rockets and other technology that will enable space exploration. And Musk is thinking big. He’s telling the world that his company will be putting people into space, putting spacecraft on Mars, and eventually sending people to Mars.

Putting humans on Mars is a huge goal, and it’s an important one for both private companies and government agencies. This kind of grand vision helps push NASA and other government space agencies — which do the slow and steady work of moving forward in some of the riskiest frontiers — move further and faster. Government organizations and private companies are all working together on many of these hard problems, but they’re pushing each other, too.

This is good in a lot of different ways. It helps us create amazing new technology and jobs that will benefit us here on Earth. Mars likely holds secrets to how life evolves on a planet like Earth.

And perhaps most important: as Americans, exploration is part of our lineage. It’s who we are. We’re people who put themselves out there and push the boundaries. It makes sense that we’re making big goals to explore this final frontier of space.

2. We’re discovering repeatable processes to solve seemingly intractable conflicts.

Stacey Connaughton is director of the Purdue Peace Project.

As part of the Purdue Peace Project, I work with everyday citizens in places including Liberia, Ghana, and El Salvador. These are countries with an array of really challenging issues. There are large numbers of impoverished people, for example. In Liberia and El Salvador, communities are dealing with the after effects of civil wars. In northern Ghana, there are inter-religious tensions between Christians and Muslims.

These are all difficult problems, but our teams have developed a four-part process to address conflicts in communities in ways that are making a positive difference.

First, we spend a lot of time talking with various stakeholder groups about the problems — seeing them from their perspective. Then we wait to see if they would like to collaborate with us.

If they do, then we develop a really inclusive group of people who have a stake in the issue and literally get them around the table for dialogue. It varies by issue, but this could include representatives of government and industry groups, women’s groups and religious groups, and youth.

That collaboration eventually leads to action. These discussions can be tense and conflict-laden, but over time — typically multiple meetings — the stakeholders themselves develop strategies and tactics that can prevent political violence and other problems. Sometimes we can lend them our expertise.

It’s an approach that works. We’ve seen it work to resolve a chieftaincy dispute in Ghana. We’ve seen it in helping to improve relationships between ex-combatants in Liberia and the Liberian National Police.

But the larger — and more important — point is that this type of inclusive model can work in a lot of different places. It’s a process that can be refined for conflicts here in the United States. This work is teaching us a lot about solving disputes and other tensions effectively.

3. We’re learning to enhance the benefits and limit the drawbacks of screens in our lives.

Glenn Sparks is a professor in the Brian Lamb School of Communication.

There’s no question that screens dominate many people’s lives these days. But we’re finally learning how to use them most effectively. Here are two examples:

We’re learning to set rules about screens in social situations. Families are making rules like “no phones at the dinner table.” Party hosts are asking guests to drop their phones in a box when they arrive at the door. Board game nights are becoming more popular. To me, this signals that our culture is becoming more sensitive to the isolating effects of this technology. We’re wired for human connection, and we’re finding ways to make sure we maintain those connections.

We’re starting to use technology for the right reasons. I do a lot of work with elderly people, and they’re using Skype and FaceTime to keep in touch with family members who they could not see very easily otherwise. Technology is tremendously positive when it helps us keep established relationships warm and close.

4. We’re generating more renewable energy than ever before.

Jeffrey Dukes is a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences.

Carbon dioxide emissions are one of the biggest drivers of climate change, and much of that is created by the burning of fossil fuels, like coal.

But in many places, the use of coal is dwindling — including in some of the most populous countries on the planet. For example, in China, coal use is on the decline, according to a study in Nature Geoscience. The country is also making major investments in renewable energy. India, too, is in the midst of a transformation. In 2016, India installed twice as much wind and solar capacity as coal.

And despite the political conversations we’re having nationally, renewable energy is taking hold in the United States in a major way in cities, states, and the corporate world. In America, new solar electric generating facilities added more capacity to the grid in 2016 than any other resource — including natural gas, nuclear energy, and petroleum combined.

Carbon dioxide emissions are one of the biggest drivers of climate change, and much of that is created by the burning of fossil fuels, like coal.

But in many places, the use of coal is dwindling — including in some of the most populous countries on the planet. For example, in China, coal use is on the decline, according to a study in Nature Geoscience. The country is also making major investments in renewable energy. India, too, is in the midst of a transformation. In 2016, India installed twice as much wind and solar capacity as coal.

And despite the political conversations we’re having nationally, renewable energy is taking hold in the United States in a major way in cities, states, and the corporate world. In America, new solar electric generating facilities added more capacity to the grid in 2016 than any other resource — including natural gas, nuclear energy, and petroleum combined.

Instead, the costs have plummeted. The price of solar panels and installation has dropped by more than half in the past decade.

There are all sorts of other benefits, too: Renewables can be a mechanism for countries to be a little bit more independent in their energy supply. In developing countries, it’s often much easier to use renewables than depending on massive and often unreliable grids.

There is still much work to do, but these are promising trends, and they’re really helping us start to address climate change.

Instead, the costs have plummeted. The price of solar panels and installation has dropped by more than half in the past decade.

There are all sorts of other benefits, too: Renewables can be a mechanism for countries to be a little bit more independent in their energy supply. In developing countries, it’s often much easier to use renewables than depending on massive and often unreliable grids.

There is still much work to do, but these are promising trends, and they’re really helping us start to address climate change.

5. A tiny portion of web users are helping make the world a better place.

Sorin Adam Matei is director of the Purdue Data Storytelling Network.

One of the things that got people really excited about the Internet was the idea that there would be a wide variety of participation. Sites like Wikipedia and Twitter, for example, provide a platform for anyone who wants to contribute. There was reason to believe far more voices would be heard.

Yet the actual statistics seem somewhat troubling. One study found that more than 50 percent of all Wikipedia edits are done by 0.7 percent of the users. More troubling still, they tend to fit a very specific profile as a white-collar male from a developed nation. Another study found that 10 percent of Twitter users contribute 90 percent of the content. This isn’t nearly as inclusive as it could be, and we might reasonably be concerned that people with their own specific agendas are controlling what we know.

But I don’t think we need to be troubled yet. I would argue that you actually want to have a relatively small group of people who are really invested to show leadership in this work. These leaders can help us do these jobs a little bit better and more efficiently. And the reality is the people who contribute most aren’t “hogging” resources. They’re performing a service. We can’t — and we shouldn’t — expect everyone to contribute equally. Nothing would get done!

To be clear: I do think it is important to try to pull everybody in and not to deny anyone who is talented the right to be part of and participants in these groups. There are certainly costs that come along with the benefits of a tiny fraction of people doing most of the work. But is the glass half full? Do these resources provide a net benefit to the world? I think yes.

6. We’re continuing to invest heavily in lifesaving scientific research.

Pamela Aaltonen is associate head of the School of Nursing, College of Health and Human Sciences.

There had been a lot of political talk about cutting the National Institutes of Health budget over the past year — in one proposal, the suggested cuts were almost $6 billion. In the end, though, Congress ultimately authorized a $2 billion increase.

Why does that matter? The NIH provides funding to scientists who do everything from bench research, which advances fundamental knowledge about the world, to clinical research, which is science that tests the safety and effectiveness of treatments for diseases and other conditions.

In the bill, much of the funding was allocated to clearly pressing issues: cancer, Alzheimer’s, and “precision medicine” that custom-tailors treatment to a patient’s genetic makeup, for example.

Of course, there are lots of different ways that scientists can get funding, including private philanthropy and corporations. But there can be conflicts of interests in these funding sources, and the findings of these studies can stay private.

Government funding is often viewed as more neutral. Also, the outcomes of the research have to become available to the public, which means we all can benefit from the progress that NIH-funded scientists make.

More money to do research in healthcare will lead to progress in our approach to disease and healthcare.

7. We’re finding ways to use online education to help America maintain its edge.

Jon Harbor is director of digital education at Purdue. In April, Purdue acquired the assets of Kaplan University, an online college.

Some national analyses suggest that for America to continue to be economically secure and at the forefront of development, about 60 percent of the population should have some type of higher education credential. Unfortunately, we’re currently stuck at about 40 percent.

One of the biggest areas for improvement is people in their 20s, 30s, and 40s who didn’t get a higher education credential but could significantly improve their lives and careers if they did.

Online education may be a powerful way to do that. For example, if you’re living and working on a farm in rural Indiana, you’re unlikely to relocate to West Lafayette or one of Purdue’s other campuses. But online education might be a way for that person to get certain kinds of agricultural education that can benefit them.

There are also ways that online education can effectively serve more people than a traditional class format. When I first started teaching, I came up with a great writing assignment — but then I realized I had 180 students. Grading that many papers wasn’t really practical. But with a digital format, I can give every student a writing assignment and then follow it up with sample answers and a grading rubric. I can have each student read the answers of three other students — which have been anonymized — and evaluate that writing. They can also self-evaluate. The result? This past spring, I had seven writing assignments and 730 students. In some ways, they learned in ways that were more useful, because they were doing the work of evaluating the work of themselves and of others.

Online education will never replace brick-and-mortar campuses. But it can complement what traditional colleges and universities are already doing and provide an effective way to reach out to the working adult population.

8. There’s a secret stress reliever: sounds of the natural world.

Bryan Pijanowski is a professor in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources.

Many of us spend our days in environments full of noisy, man-made sounds: machines, sirens, cars on the highway outside our windows. Studies on human psychology show that this kind of noise stresses us out, even if we don’t consciously realize it.

But if we add birdsong — even from just one bird — people will suddenly feel more relaxed. In a Citizens for Science project called Record the Earth, we discovered that water is a universally pleasing sound.

Scientists have shown that hearing sounds from nature reduces hypertension. It has a positive influence on our behavior, our psychology, and our physiology. In some ways, it makes intuitive sense: We’re all connected to nature. But we often don’t pay as much attention to the natural sounds around us as much as we should or in ways that can really benefit us.

I often encourage people to go outside in nature and listen to the rhythms of sounds around them: the crickets, the frogs, the cicadas, the katydids. If you can tap your foot to the sounds of nature, it almost guarantees that you’re living in a healthy environment. Those sounds are the base of the food chain making their presence known.

And these sounds benefit us on an individual level quite a bit. Natural sounds make us happy. All we need to do is notice them.