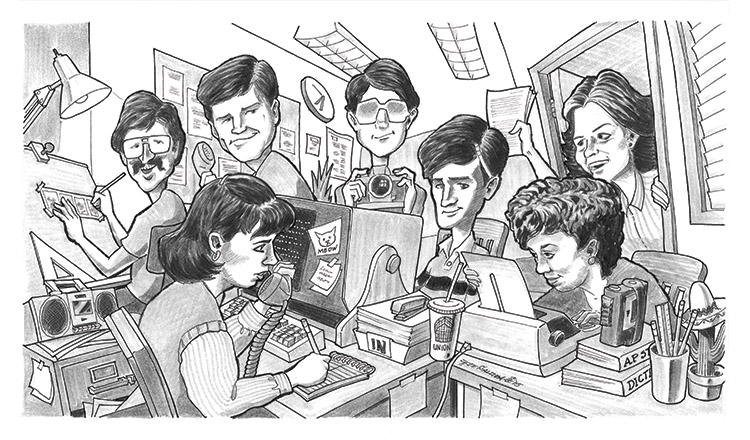

I wish we had a staff picture.

If we did — the Purdue Exponent, 1984–85 — I could draw arrows from those faces of 30 years past, the faces of students putting out a newspaper at a university known for engineers and astronauts, a university that didn’t even offer a journalism degree.

The arrows would extend to the photo’s margins. There, I would scribble career highlights, charting what became of us.

Ginger Thompson (LA’86) became Mexico City bureau chief for the New York Times.

Brandt Hershman (LA’10) became majority leader of the Indiana State Senate.

Jay Fehnel (LA’84) became chief operating officer of Tribune Media Services, an enterprise with 500-plus people.

Betsy Liley (LA’85) became chief development officer for the Humane Society, in the United States and internationally.

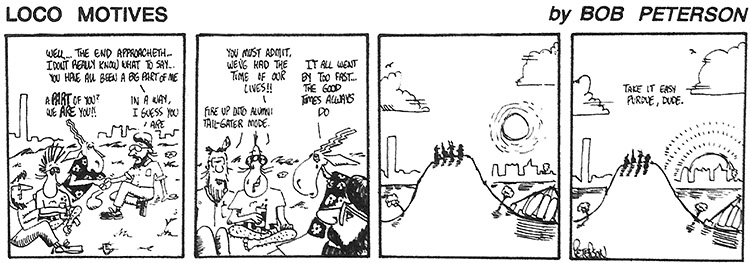

Bob Peterson (ME’87) became a top creative force at Pixar (animator, screenwriter, director), where he helped bring the world Up, a movie so beautiful it made me cry.

I would keep drawing arrows — Chris Maloney (LA’85) became a high school principal in Maryland, Brian Andrews (M’84) a vice president at Sprint, Carolyn Holmes (LA’85) the director of special events for Major League Baseball, David Wierzal (LA’84) an English teacher and head football coach in Illinois — and for me, the arrow would point to reporter, a career I can’t imagine life without, and a career I can’t imagine having without the Exponent.

And in all those arrows and marginalia — what became of us — I would see what came of our work: hundreds of millions of dollars raised for worthy causes; hundreds, perhaps thousands of students taught; newspaper stories that changed laws and saved lives; and movies that made people laugh and think. And that’s hardly exhaustive. There would be other arrows, with other ripples.

Purdue may not offer a journalism degree, but the Exponent offers a journalism education. Some lessons are straightforward — dealing with deadlines, working as a team, writing clearly and concisely — and others, less so. This year, 30 years after leaving Purdue, I reached out to some members of our long-ago staff to ask what that education has meant to them.

Ginger Thompson is now a senior reporter at ProPublica, which is a powerhouse in investigative journalism. When we spoke, she was working on a story to be published in The New Yorker. Her previous stops included the Baltimore Sun, where she co-wrote a series exposing the United States’ complicity in the atrocities of a Honduran death squad, and The New York Times, where she took part in a Pulitzer Prize-winning series on race in America.

Ginger came to Purdue to study computer technology. Coming from a “working-class to poor family,” she wanted a sure thing, a career with stability. But she found that Purdue wasn’t the most comfortable fit for an African American student. And she found that her major didn’t suit her. “I was so unhappy my first year,” she says. Having been editor of her high school yearbook in Texas, she gave the Exponent a try. Soon, she discovered, “I was spending more and more time in the Exponent office, and less and less time in the computer lab.”

“I felt like I belonged there,” she says of the Exponent. “I was there all the time, in that office. And I was there all the time because it mattered to me.” The second semester of her freshman year, she changed her major to communication. In time, she became the Exponent’s managing editor. Later, during her journalism career, what stayed with her was an appreciation for the independence of the Exponent, which receives no funding from the school and no editorial oversight. “It wasn’t part of the university. In fact, it took great pride in challenging the university. That stuck with me in terms of speaking truth to power.”

When I spoke with Brandt Hershman, he had just put a new engine in his pickup. Only a 2009, the truck had already turned over 240,000 miles — a function of Brandt’s commute from Tippecanoe County to Indianapolis, where he is majority leader of the state senate. In addition, Brandt had recently passed the bar, having finished a law-school program at Indiana University in Indianapolis, during which he also studied abroad in Beijing, Prague, and Vienna. “Nothing like 25 years of procrastination,” he says of becoming a law student.

At Purdue, Brandt majored in political science. He says of the Exponent: “I just kind of did it on a lark, as a part-time thing.” But one job rolled into another: copy editor, photographer, paste-up, opinions editor, assistant managing editor. He even worked in the pressroom, stacking thousands of papers at 3 in the morning. “I certainly learned the value of hard work,” he says. He befriended an “amazing group of people,” including a cartoonist pursuing a master’s degree in mechanical engineering. “I remember saying to Bob Peterson, ‘What is wrong with you? You’ve got this great career ahead of you — and you’re drawing cartoons?’ I think he just smiled and gave me the equivalent of a pat on the head — and then kept on drawing.”

As a lawmaker, Brandt has discovered parallels between journalism’s inquisitive approach and legislation’s deliberative process. Plus, he says: “With newspapers, you’re covering a different subject every day. I just came out of a legislative session in which 1,200 bills were introduced.” Reflecting on his years at the Exponent, he says: “I haven’t forgotten the challenges faced by reporters, and the inherent skepticism that’s part of their DNA. I understand the job better than some of my colleagues.”

At the Humane Society, an animal-welfare group in more than 50 countries, Betsy Liley leads a staff of about 80 people while helping raise more than $100 million annually. She was previously a national director at Planned Parenthood, and before that helped manage fundraising for NPR and Purdue, where she was an assistant vice president.

At Purdue, she went to the Exponent “the first I could my freshman year and never left,” she says, eventually becoming editor in chief. Once, she wrote a goofy column about white shoes — when they should be worn, when not — that became the 1980s equivalent of viral, complete with protests, with one guy even showing up at the Exponent in white shoes and white belt, saying he had a bomb strapped to his chest. (He did not.) “It was a little surreal the way that took off,” Betsy says. “I think I learned that at the Exponent. I don’t know how the story is going to end.”

There are mistakes — and there are mistakes in 36-point type, published in 20,000 newspapers.

She also learned to appreciate business. Circulation was audited, advertising was sold, and financial commitments were made. When a student organization, in the predawn hours, stole copies of an Exponent special section, it was not a thing to be laughed off. During the night Betsy searched alleys and dumpsters, looking for those copies, knowing she needed to make things right.

At the Exponent, Betsy discovered “this amalgam of people who brought this really diverse skill set.” One student majored in nuclear engineering, another in aviation. “If we had all been in the same classes all day, what would we have written about?” she says. “We really represented our community. We studied different things, we lived in different places.” There was no political lockstep, either. Betsy and Brandt could hardly have been further apart. Thirty years later they’re still sparring, now on Facebook, debating such topics as lessons to be gleaned from the French economy.

When I came to Purdue, I majored in computer science. While Ginger lasted into her second semester, I lasted into my second week. Then I transferred into political science, which claims to be a science, but is not. With no newspaper experience — not from high school, nor class — I began working at the Exponent and eventually became editor.

I loathed typos. And because I thought I was immune to them, I could be merciless on those who weren’t. One of our copydesk chiefs, Laura Kursell, suggested I try her job for a night. I took her up on it. The next morning, I found on my desk a marked-up copy of the paper. With a highlighter — a shockingly red, remarkably fat highlighter — Laura had circled a typo I had missed, and not a typo deep in some story, but in a headline. There are mistakes — and there are mistakes in 36-point type, published in 20,000 newspapers.

The obvious lesson was humility. But there was also another. I worked for a daily newspaper. And you know what the best part of that is? The next day there is always another paper. When there’s another paper, there’s another chance. When there’s another paper, there’s a statute of limitations on moping. For 30 years now, I’ve been looking forward to another paper — each with an opportunity to do a little better.

When we were at the Exponent, the publisher was Pat Kuhnle. He is the publisher still.

“I would say that the success of the Exponent has more to do with Pat Kuhnle’s contributions than anything else,” Brandt says. “He’s allowed generations of students to make mistakes and learn from them, without interfering in editorial content, other than to offer advice when asked.” Says Ginger: “He was the guy who said, ‘Don’t be afraid. I’ve got your back. If you guys believe in this, then go ask the question.’” Betsy gives thanks to his “fierce sense of right and wrong.” It was Pat who drove her around that night, the two with flashlights, looking for those stolen papers.

Pat, too, attended Purdue — and worked for the Exponent. As a freshman in 1974, he read an Exponent column he found offensive. So he wrote a letter to the editor and carried it down. The paper printed his letter — and misspelled his name, turning Kuhnle into Kuhmle.

The first person Pat met at the Exponent was Bill Moreau, who, years later, became a Purdue trustee and chief of staff to Governor Evan Bayh. One of Pat’s first sports editors was Carolyn Curiel, who became a senior speechwriter for President Bill Clinton, a US ambassador, and is now executive director of the Purdue Institute for Civic Communication. So our staff in 1984–85 was not unique in producing ripples. Other Exponent alumni have gone on to become chief justice of the Indiana Supreme Court; an Emmy Award-winning story artist, working on such shows as SpongeBob Squarepants, and leader of the scientific effort to build an elevator to space.

Pat has witnessed the before and after, seeing students anxious about asking a single question become editors unafraid to demand public records. “You just think of how meek people are when they come here,” Pat says. “When they leave, they are not meek.” And Pat has helped the Exponent remain vital, despite the struggles of newspapers nationwide. The Exponent’s print circulation has dropped from 20,000 to 12,000, but last year, when a student was shot and killed on campus, the Exponent’s online coverage drew a half-million page views that day alone.

Students who know they want to become journalists don’t generally come to Purdue. They go to Indiana University. They go to Ball State. At Purdue, journalism is a side road — one that students take without a helping hand from the university, a fact for which many of us remain grateful. “It would have taken some of the fun away from the place,” says Jay Fehnel, another member of our 1984–85 staff. Says Betsy: “Can you imagine if Pat was a professor and he was grading what we did? It would have changed the whole dynamic of the place. Would we have taken the same risks? Would we have done the same things? I don’t think [so]. We built the newspaper we wanted to have.”

Looking back at our staff from 30 years ago, I sometimes wonder why we have no staff picture.

I think the answer is, we were busy putting out a paper.

Ken Armstrong (LA’85) is a multi-Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist currently working for The Marshall Project.