Faculty share transformative visions for our future.

We live in a world of small thinking.

We live in a world where tomorrow’s world leaders engage in Twitter spats, where national conversations revolve around Bachelorette plot points, and where fast-food menu changes lead to vigorous debate.

But what if we decided it was time to break free from these constraints and think much, much bigger? What if we considered some of the ways we could make entire populations of people healthier, happier, and wiser? What if we thought about ways to share information that could make us all safer?

We asked faculty members across Purdue to dream up ideas that could solve some of the biggest problems in their field. Whether you agree or disagree with their assessments, we hope their ideas will make you think.

Create a well-funded facility to study human-animal interactions

Alan Beck // Director of the Center for the Human-Animal Bond

We’ve always known intuitively that animals can have an enormously positive influence on our lives — just ask anyone who has a dog. But it’s only been in the past few decades that researchers have begun to systematically study the human-animal bond.

For example, a 1980 study in Public Health Reports found that after a heart attack, animal owners had significantly better one-year survival rates. We’re finding interesting links on the positive impact that animals can have on people with autism and Alzheimer’s, too.

This kind of work is being done in many areas: psychology, biology, and animal science, for starters. But animal centers that study this human-animal connection are almost always virtual, not physical.

This should change. My big idea is to have an actual facility to study the many types of human and animal interactions. That might mean spaces for therapeutic horseback riding or training service dogs. It might look at the ways that children interact with animals like guinea pigs or even robotic dogs.

A center like this — where we could record these experiences on video, where we could have space with one-way mirrors to study live interactions, and even have permanent classroom space — would make a huge impact. This area is growing rapidly, and researchers are getting grants from major federal agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health, and private companies, including Mars.

This is not a niche issue; this is a major part of our lives. Nearly two-thirds of American households have a companion animal, and a center like this would give us many more opportunities to examine, appreciate, and understand this human behavior.

Develop powerful digital time capsules

Aniket Kate // Assistant professor of computer science

What’s a digital time capsule? We all know what time capsules are: containers that allow us to store information and items safely so they can be shared with future generations of people. But in a digital world, we must rethink this idea. Digital information brings new challenges — and new opportunities — to store and retrieve information. Digital information is much easier to copy, modify, and share than physical data. Developing digital time capsules will be essential to maintain confidential information and share information with others when certain conditions are met.

Developing digital time capsules will be essential to maintain confidential information and share information with others when certain conditions are met.

How might we make use of them? The simplest example of a way to use a digital time capsule is with predefined time periods. The government, for example, might want to declassify specific information after 10 years or 25 years, and a digital time capsule would allow for this. But there are also more interesting ways to think about this kind of “information escrow.” Perhaps you want to make sure your loved ones have access to your login information after your death so they can manage your financial and personal affairs. A whistleblower could share information about a crime, but could avoid prosecution by ensuring that the information becomes available only after his or her death. There would be different kinds of “keys” that would allow the information to be accessed at these specific times.

Some believe that such time capsules could help victims of crimes who fear public backlash, like in the Bill Cosby case. Could they? Yes, a digital time capsule would allow them to share details of crime in a report, but have it released only if another person also reported similar misconduct by the same person.

Aren’t these ideas much more complicated than a time capsule? The ease of copying digital information without leaving a trace makes designing solutions for these kinds of problems difficult. Moreover, it isn’t just about keeping information private — it’s about finding ways to share information at exactly the right time.

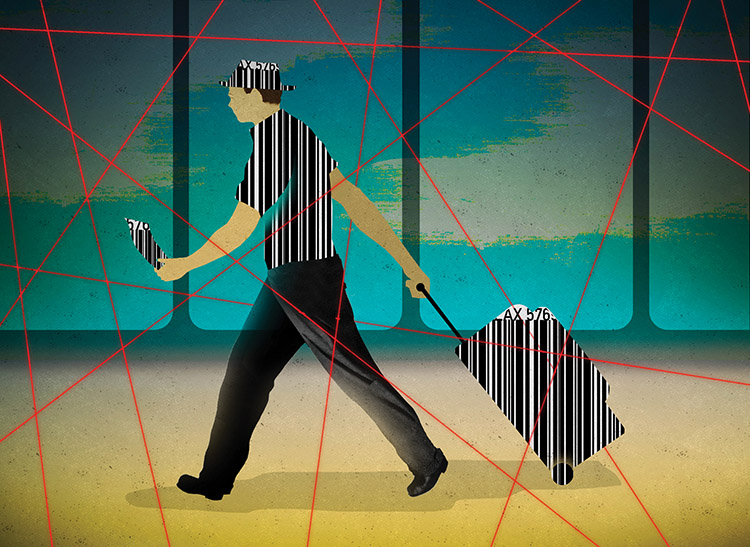

Create in-motion screening for airport security

Karen Marais // Associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics

The problem: Nobody likes to go airport security — it’s cumbersome, you’ve got to take your shoes and belt off, and you never know if you’re going to sail through or it’s going to take an hour and a half.

The impact: On an individual basis, it’s a hassle, but across the system, the cost is far higher. These problems lead to millions of dollars in lost productivity, the extra costs of rescheduling passengers who missed flights, and the sheer dread of airline travel that leads some to drive, take a train, or just stay home.

The solution: In-motion screening. In a future world, you’d scan your boarding pass and ID when you arrive at the airport. You might set your bags next to you on some sort of conveyor belt as you move through the system, and they would be checked for explosives. A scanner would check for dangerous items on your body. If something seemed suspicious, only then would a human intervene. Essentially, I envision a system that would simply allow you to get out of your car and walk to the gate, without the security bottleneck we’ve come to expect.

I envision a system that would allow you to get out of your car and walk to the gate, without the security bottleneck we’ve come to expect.

The model: I think airports could take cues from places like Disney World, that have gotten really good at managing queues. You’re constantly moving, you’re getting updates, and you’re learning about nearby restaurants and shops. The technology for many of these approaches exists already, and it’s only getting better.

The outcome: Over the long run, I think this system could do even better than the human systems we have in place now. It wouldn’t just make our trips to the airport more efficient. It could make them safer as well.

Use traffic data to make strategic infrastructure investments

Darcy Bullock // Director of the Joint Transportation Research Program

If you’ve ever used Google to check the traffic, you’re familiar with the color-coded maps that tell you where — and how much — traffic is backed up. We’ve been collecting this information for years in 15-minute increments, and we now have 35 billion records for Indiana alone.

Currently, that information is targeted at the consumers to help them, make decisions in the next two minutes on their traffic route or determine when to leave to get to their next destination.

But there are ways to look far beyond that. How can agencies use that data to better manage the system, and then more importantly, how can they prioritize investments?

For example, we never look at a single interstate highway such as I-70 or I-80 from coast to coast. None of the [construction or improvements] are coordinated. For the private sector, that can be frustrating: they often place a high premium on reliability, and they don’t like uncertainty. They can’t have factories sitting idle while they’re waiting for supplies stuck on a truck in Los Angeles. It’s a huge issue: $650 billion in freight passes through Indiana alone every year.

By using this data, we can systematically analyze some of the biggest problem areas so that we can make the most effective, strategic capital investments. If we understand at a national level where our biggest pockets of congestion are, we can do a better job of coordinating among states, and we can start to make decisions that benefit the whole country, instead of just choosing the most locally optimal decisions.

Persuade people to choose a diet that has balance, moderation, and variety

Richard Mattes // Distinguished professor of nutrition science

Why do you think improving our diets is such an important goal? The prevalence of obesity has been increasing for decades, and presently about 40 percent of American women and 35 percent of American men are obese. Obesity is associated with many complications, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, sleep apnea, and social stigma.

So what’s the solution? If I could, I would find a way for all people to follow a diet that is nutritionally balanced, moderate in portion sizes and eating frequency, and that has variety that people enjoy. I would make sure that they ate as much as their bodies needed, not more or less. This advice is not new,

revolutionary, or exciting, but if practiced, it would lead to marked and widespread health benefits. We need to find ways to educate and persuade people to choose more healthful diets and lifestyles.

That doesn’t sound so tough. Is it? It’s really complicated. Access to food is so high, and the food we have available to us is so inexpensive, convenient, and palatable. We’ve undergone a cultural shift where it is acceptable to eat and drink anywhere — in the classroom, in our cars — and that means we can indulge almost constantly. We have to learn how to moderate our ingestive behaviors.

Is it just a matter of education? We need education that changes behavior. We will need adjustment motivations and expectations. Food is often the stimulus that brings us together. It’s a way to celebrate important occasions. It’s a source of entertainment. But often, it’s not what our bodies need. We should view food as sustenance. When we glorify food, we have to realize that there is often a price to pay for that.

Help young people gain life wisdom earlier

Sherylyn briller // Associate professor of anthropology and faculty associate in the Center on Aging and the Life Course

We can teach a lot of things to our students in the classroom. But we also know that there are some things that most of us can really only learn through lived experience. The question I’m interested in exploring is how might we educate people to gain the wisdom that we typically accumulate over the course of our lives faster than we do now?

For example, in healthcare, we might teach students how to deal with aging patients who struggle with issues like mobility and memory. They can understand issues on an intellectual level, but it’s not until they experience their parents aging, or notice their own aging, that they say, “Ah, I get it now.”

There are certain life-changing transitions that people go through to bring them to this point of greater empathy, but we should always be looking for ways that we can infuse that empathy through the educational process.

That kind of education can look like a lot of different things: service learning, internships, and study abroad. Sometimes I will have students go out into pairs and observe something specific, and then ask them to report on it. They never come back with the exact same field report, because they all bring that powerful combination of who they are and what they’ve learned together in different ways. It can be really eye-opening for students to see how much we are shaped by our personal experiences, education, and culture. We should always be looking to include these and other ways of learning in students’ college experience.

In the end, I don’t think we can entirely shortcut the process. Some things will always take time. But I think it’s important to try to move in that direction.

Focus on real-world problems to make learning authentic in K–12 schools

Carla C. Johnson // Professor of science education and associate dean

for research, engagement, and global partnerships

The problem: Today’s employers are clamoring for people who have the 21st century skills of problem solving, critical thinking, and collaborating with others. They’re not finding it in as many people as they’d like. In some ways, that makes sense. So much of students’ classroom learning is incredibly lightweight: memorize this definition, fill out this worksheet. It’s an easier way to assess learning, but it’s not the best way to learn.

The big idea: One idea that many people are working on right now is an integrated STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) approach where students really grapple with the real-world problems we face and try to come up with potential solutions as the context for learning in K-12 schools. For example, we hope to be able to send people to Mars by 2030, which is the time that today’s young students will be adults. What if we had students thinking about things like what it would take to get there, and how we could sustain life there? In other words, once we’ve accessed information about a topic, what are the ways that we can apply it to help move the world forward in positive ways?

The roadblocks: Certainly, this approach to learning takes longer. It requires that kids have the time to do research and think about what the right questions are. There’s no way we could use this approach and try to cover the breadth of subjects that we currently cover in science and other disciplines today. But we also know that students in other countries who are outperforming the US have been successful by covering fewer topics but going into greater depth on them.

The impact: In the end, learning in the context of real-world problems makes learning more meaningful, builds deeper understanding that is retained much longer, and will provide students with critical skills that will help them in whatever career they pursue, whether it’s STEM-

focused or not.

Make a tobacco-free lifestyle a basic human right

Karen Hudmon // Professor of pharmacy practice

The problem: Tobacco is the leading preventable cause of death in America. Each year, tobacco use costs the United States nearly $300 billion in healthcare expenditures and lost productivity. That doesn’t even begin to address all of the other consequences, such as the emotional impact of losing a loved one.

The big idea: In my perfect world, a tobacco-free lifestyle would be viewed as a basic human right. Patients, whether insured or uninsured, would have unlimited access to professional assistance and effective medications for quitting.

What it might look like: Every patient should be asked about their tobacco use at every visit with a healthcare provider, and hospitalized patients who use tobacco should be provided with appropriate medications to treat their nicotine withdrawal during their hospital stay, and a cessation plan should be discussed as part of their discharge. All costs associated with professional counseling and cessation medications would be covered by insurers. I’d also eliminate all tobacco advertising, eliminate tobacco sales in all pharmacies, and focus on smoking prevention in youth.

The impact: Today, more than one in five adults use a tobacco product, despite decades of evidence indicating that smoking negatively affects virtually every organ of their body. In terms of risk factors, there really isn’t anything that’s more harmful than smoking. That’s why I believe that equipping individuals with effective methods for quitting and reducing environmental cues for relapse are essential to reducing the heavy burden of tobacco use.

Create a map of all cell interactions

Angeline Lyon // Assistant professor of biochemistry

One of the things that would give us greater understanding into life itself is to map out everything that happens in a cell. It’s the difference between admiring a rocketship and getting in, taking it apart, and seeing how all the pieces fit together.

In most disciplines — biochemistry, molecular biology, cell biology — people end up working on one pathway involving a handful of protein or other biological molecules. There’s good reason for that: living things are complicated.

For example, all cells have a membrane, which is made up of molecules that have really similar properties. And across that membrane, the cell has to be able to search the outside environment and communicate and understand specific signals. There are all sorts of signals — taste, touch, smell, light, heat, and cold — that get communicated across that barrier and activate things within the cell. Just to understand that membrane alone — how it got there, how it’s organized, and how it fits together — is a huge challenge. And there’s so much more to a cell than just a membrane.

Despite mathematical models, we don’t really know how everything works across a larger system. There are so many ways that a tiny change in one place can ripple out to entirely different areas, like the butterfly that flaps its wings in Tokyo and causes it to rain in San Francisco. When we see changes to one area, how does it affect other areas, both in the short and longterm?

There are so many ways that a tiny change in one place can ripple out to entirely different areas, like the butterfly that flaps its wings in Tokyo and causes it to rain in San Francisco.

Lots of scientists are working on our own little page of this larger story, but we haven’t figured out how to put the pages together to make a chapter, or the chapters together to make a book. If we could stitch all those together into a coherent story, it would be amazing.

Build an app that forecasts weather and climate hazards

Dan Chavas // Assistant professor of atmospheric science

Weather hazards affect people and businesses every day, both in the short term and the long term. I’d love to find a way — like a smartphone app — to pull together the best information we have to give people the knowledge they need exactly where and when they need it.

First — and we have this already with some weather apps — are the short-term weather hazards. Is it going to rain on my run? Will there be snow for my commute? Do I need to find shelter to protect myself from a tornado that touches down? These are things that can really disrupt people’s lives.

I’d also like to see some medium-term forecasting. For example, we could help farmers understand their hail risks for the upcoming growing season. We could give forecasts that would help couples plan the best weekend for their outdoor wedding or a vacation. We could provide the information that would help retailers like Home Depot and Walmart understand what kind of winter lies ahead and how many snow shovels and snow plows to have for their customers.

Then, finally, this app would help people understand the long-term risks for weather or climate. So, maybe a business or a person wants to build a house or a building. The app could help them understand some of the longer-term risks, like how often they might experience a tornado or the effect of potential droughts or rising sea levels.

Certainly, there’s a lot that science still needs to work out, but our models are getting better at forecasting all sorts of weather hazards. But all of our information doesn’t help if we can’t get it to people in ways that are useful and accessible. This is information that, if it gets to people when they need it, could both improve lives and save them.

Erin Peterson is a freelance writer.