As Baby Boomers start cleaning out attics and basements, many are discovering that Millennials are not so interested in the lifestyle trappings or nostalgic memorabilia they were so lovingly raised with.

Recently, Kathy Hamilton Beno (HHS’82, M’82) and her husband, Greg (M’81), decided to move. Their four children had left home, and they no longer needed their spacious five-bedroom home in Roswell, Georgia. But before they could downsize to a smaller townhouse, they needed to get rid of much of their stuff. And they had a lot — enough to fill multiple storage units.

“There was a cherry dining room set, big sofas, lots of beds, posters, and artwork from the places we’d lived,” says Beno. But when she told her kids to take anything they wanted, the response was definitive: no thanks. “They didn’t want any of it,” says Beno. “They don’t want hand-me-downs. They want new things that look good.” It was a far cry from Beno’s own postgrad experience. She and Greg were married only seven weeks after her Purdue graduation and were more than happy to start their new lives together with secondhand bookshelves. “It’s not that way anymore,” Beno says.

Beno’s experience isn’t unique. As Baby Boomers across the country have started to downsize, thrift stores and antique shops have been inundated with their collected belongings: all of the furniture, artwork, and memorabilia that they can’t bear to throw away — but which their adult children don’t want. There may be a number of reasons for this. Today’s graduates are no longer settling down immediately after college but are weaving more itinerant professional and romantic paths. And when they do finally establish roots, it’s often in cramped city apartments, where there simply isn’t room for mom’s antique armoire or grandpa’s extensive coin collection. Millennials may also be less attached to these kinds of heirlooms. Instead of making scrapbooks, they mark events by posting to Facebook and Instagram. This generational shift has its benefits (goodbye storage units!), but it has some archivists concerned. They argue that physical objects inspire a unique connection to the past, something the digital can’t replicate. Equally important, physical artifacts may be more durable than anything we store online. Decades from now, they say, our most precious memories may not be accessible when we want them.

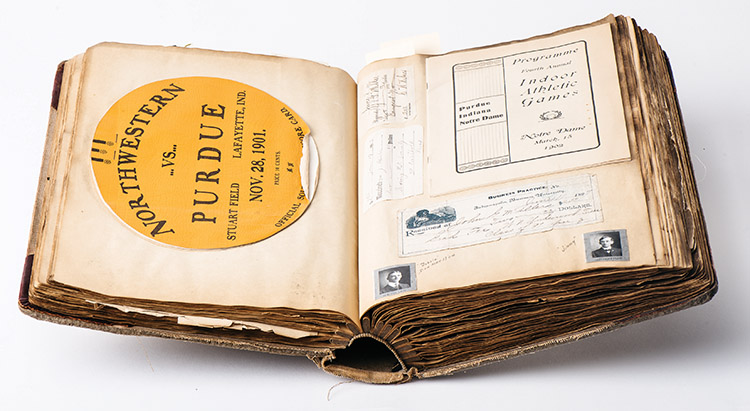

Purdue has a 15,000-square-foot facility dedicated to storing and preserving the university’s historic papers and artifacts. The Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center houses 7,000 feet of documents and the effects of university-affiliated legends like Nobel Prize-winning chemist Herbert C. Brown, astronaut Neil Armstrong, and aviator Amelia Earhart. There are collections from all of Purdue’s past presidents, including even the Nerf gun that President France Córdova used during a campus-wide game of Humans vs. Zombies. The oldest University-related object on hand is the Board of Trustees minutes from 1865, before the university officially existed. And of course there are large collections of student memorabilia. “Earlier generations of students kept photo albums or scrapbooks, invitations to events, dance cards, and programs for the different events they attended,” says Sammie Morris, director of Archives and Special Collections.

In the last six or seven years, Morris has been inundated with calls from Baby Boomer graduates who want to donate their college memorabilia. “About a third of the time when we get donations from alumni, they say, ‘I don’t think my children would appreciate these things.’ Or they think it would be a burden for their children to have to keep it,” says Morris. What accounts for this sudden influx? Morris isn’t sure if Millennials really have less interest in these artifacts or if young people simply are not focused on family history at this stage of life. What she does know, is that for today’s students and recent post grads, “their own memories are mostly digital.”

“What they try to remember about their lives appears on social media or online, so they haven’t experienced that sense of nostalgia — that happy feeling you get by picking something up,” she says. “When we have classes of students come into the archives, they’re fascinated by physical materials. They’re not used to seeing old things.”

Kristina Bross, a professor in the English department, sees this allure for her own students. “The smell and touch of material objects is significant and meaningful,” she says. “I’ve never taught a class with archives that students haven’t gotten incredibly excited.” Bross teaches an Honors College seminar in which freshmen investigate the historical and anthropological significance of objects preserved from the 1903–04 school year. This year’s freshmen studied everything from a box of bobby pins that belonged to the wife of Purdue’s fifth president, Winthrop Stone, to a pair of cheerleading pennants.

“The smell and touch of material objects is significant and meaningful. I’ve never taught a class with archives that students haven’t gotten incredibly excited.”

Kristina Bross

Allison Schwam investigated a photograph featuring one of school’s few international students of the day. The photo shows an Indian student from Bangalore and five of his dormmates, who are dressed up in sari-like bedsheets. Discovering this photo in the archives and searching for clues about its origin had a profound impact on Schwam. “It gave me an existential crisis,” she says. “One day we’ll all be gone, and you’d hope there will be some trail that leads someone to you.”

Schwam says Professor Bross’s class has changed her attitude toward nostalgic objects in her own life. For Schwam’s last birthday, her grandmother gave her a family heirloom: a decorative plate shaped like a leaf. “It was a gesture well received, but it didn’t have a whole lot of meaning to me,” Schwam says. “I don’t really know what made my grandma think, ‘I want this in Allison’s life.’” But now, she says, “the archives class has made me super-interested in wanting to know why she thought the plate was so important to keep and pass on.”

Professor Bross’s class has also led Schwam to think deeply about the role that photographs play in her own life. These days, Schwam and her friends snap photos constantly. This is quite different from the early days of photography, when pictures were posed and took time to develop. Learning this, says Schwam, “made me realize how much a photograph can matter.” On the one hand, she thinks today’s extensive digital record will be a boon for future generations who want to learn about student life in 2016. “From prom to selfies to eating a burger,” every moment will be documented. But there are also so many images that “it makes each individual photo have less significance,” she says.

This observation reflects broader concerns among archivists. “The huge volume makes the effort of organizing and preserving [digital memories] that much harder,” says Morris. “In the early days, photographers would only print the best photos. Today you could have hundreds of images from just one event.” Moreover, preserving the digital is more complicated than many people think. Morris explains that since many digital images are compressed, they lose a little bit of information every time you open them. Over time, your treasured photos will look increasingly fuzzy. At some point, you may not be able to access them at all. “As you get new hardware and software, that old file will not remain readable more than ten years from now, unless you’ve taken active steps to migrate it to current technology,” she says. “I recommend that if people are getting married or having a baby, they have professional, high-res images taken. And then print them out, even though that seems antiquated.”

Neal Harmeyer, a digital archivist who team-taught the freshman seminar with Bross, agrees. “A lot of us have had our phones die,” he says. “Physical prints are the only way to get that material.” He adds that our dependence on social media platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, and the like, has lulled us into a false sense of security that “our memories will be there when we need them.” If the company goes out of business or experiences a data loss, you could lose everything. That’s the benefit of shoeboxes and scrapbooks, says Harmeyer. “You have control over your personal exhibitions.”

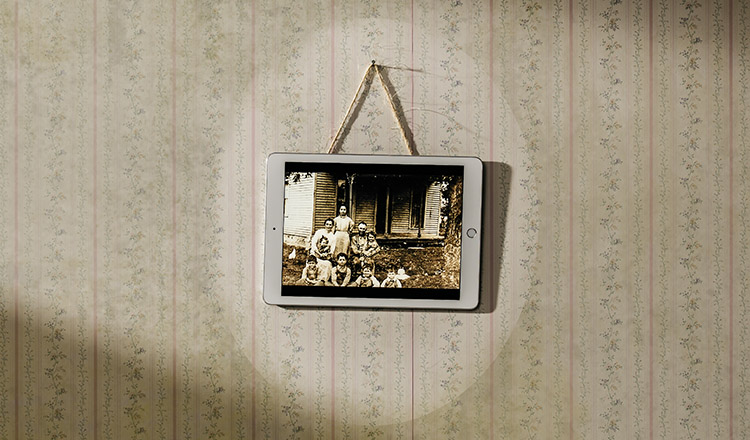

Which doesn’t mean that digital collections aren’t important. Purdue has operated a digital archives since 2005. The university collects and preserves information on platforms ranging from floppy discs to VHS tapes to flash drives. It has even started cataloging the websites hosted by student organizations as well as tweets linked to campus events. Bross says digital collections will be as important to future generations as physical archives are today. “In 50 years, if people want to look at tweets, it will feel just as particular to this time and special and opaque,” she says. “Nobody will know what the abbreviations and acronyms and slang mean. We’ll have to dig into that like we do with postcards.” It’s possible that when today’s Millennials become parents and grandparents, they’ll have similar concerns about their own kids’ lack of appreciation for memories stored on iPads and iPhones.

Still, it’s difficult to imagine that viewing images on these electronic platforms would have the same visceral effect as sorting through a box of photographs. “The digital version will never replicate the scrapbook,” says Morris. “They have layers. You can flip them up and read the front and back. The digital version is flat. It doesn’t have the heavy dusty pages you’re turning and the smell, or that small stain on the page that was maybe from someone’s tears. There’s a stronger connection to the past with the physical.”

This is something Schwam has come to appreciate. One student photo she uncovered in the archives featured a bodybuilder with the words “yours truly” written on it. “You could pick up his sense of humor,” she says. And so she’s keeping her own small collection of artifacts for posterity. “Movie stubs, little things from the places I’ve been, random knickknacks. It’s cool to think that maybe a hundred years from now, someone can piece together what my life is like.”

And she’s not the only one. Kathy Beno’s 30-year-old son, Tom (T’08), may not have accepted the hand-me-downs his parents offered, but he’s holding on to his own collection of memorable artifacts. “I like saving things with that nostalgia,” he says. An entire wall in his 1,000-square-foot apartment in Washington, DC, is devoted to Purdue, including signed photos of basketball coach Gene Keady and basketball star Robbie Hummel. He and his wife, also a Purdue grad, have stored their Greek paddles in a closet. Tom Beno says that one day, if he and his wife move into the suburbs, he’d like to take some of the more important objects his mother had offered him: childhood T-shirts, team photos, and a scrapbook of his high school newspaper articles. “Someday I’ll want it,” he says. In the meantime, he’s happy to let his parents keep all this stuff in their new townhouse. “Their place is still huge compared to ours,” he says. “We laugh that they think they’re downsizing.”

Jennifer Miller is a freelance writer.