A well-timed case of appendicitis spared John Wooden’s life. But the Boilermaker who died in his stead aboard the USS Franklin was never far from his mind.

It has been more than 70 years but Nancy Wooden Muehlhausen remembers it to this day. The fear. The anxiety. The unknown. Ten-year-old girls aren’t supposed to be wracked with those emotions.

It was 1944. World War II was raging. Muehlhausen’s family was visiting Grandma and Grandpa in Indiana before her dad was to be deployed in the navy to do his part in the war effort. She knew something serious was going on with her daddy, John Wooden (HHS’32, HDR HHS’75).

“The trip was cut short so Dad could undergo surgery,” says Muehlhausen. “His appendix had to come out. I recall having to rush back to see the doctor. It was a scary time for a number of reasons.”

Turns out, it was a surgery that would save the life of John Wooden in more ways than one. Because of the procedure, Wooden wasn’t deemed healthy enough to be deployed on the USS Franklin aircraft carrier in January 1945 on a mission in the South Pacific. In March 1945, the Franklin would undergo a deadly siege from Japanese planes. Hundreds would die — including the man who replaced Wooden on the ship: Fred Stalcup Jr. (HHS’37, MS HHS’37).

Here is where the irony gets thick: Stalcup and Wooden knew each other. Each was a Purdue athlete. In fact, they were Beta Theta Pi fraternity brothers. At the time, Wooden had no idea Stalcup was the man who took his spot aboard the USS Franklin.

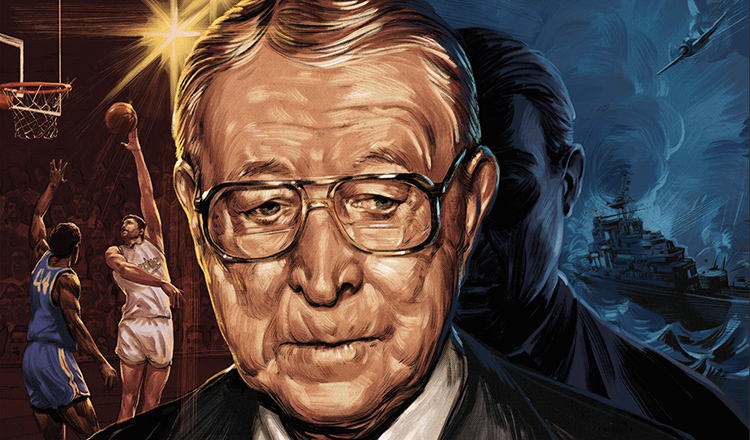

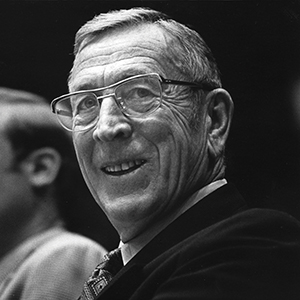

The world knows how life turned out for John Robert Wooden, one of four sons born to Hugh and Roxie Wooden, who endured a hardscrabble existence in Martinsville, Indiana. Wooden went on to become an American treasure, coaching UCLA to dizzying heights. He arguably is the greatest college basketball coach ever, impacting the sports world with a gentlemanly style built on his famous life-guiding Pyramid of Success. His words were golden.

“Learn as if you were to live forever; live as if you were to die tomorrow.”

“The main ingredient of stardom is the rest of the team.”

“Ability is a poor man’s wealth.”

“Talent is God-given; be humble. Fame is man-given; be thankful. Conceit is self-given; be careful.”

Fred Leon Stalcup Jr.? He never got a chance to build a life after March 19, 1945, the hellish day the USS Franklin came under attack from Japanese dive bombers in the Battle of Okinawa.

This is the story of two Purdue athletes whose lives are forever linked because of a monumental twist of fate. One is a basketball icon, a Purdue All-American who led the Boilermakers to a 1932 national title before becoming the Wizard of Westwood who led UCLA to 10 national championships. The other is a heroic serviceman who gave his life to this country and whose story languishes in anonymity.

Call to Serve

It’s Sunday morning, December 7, 1941. It’s not even 8:00 a.m. yet. It’s quiet in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. It’s always quiet on Sunday mornings. That’s when it happened: two waves of Japanese planes scream across the calm Oahu sky after being launched from a fleet of six aircraft carriers. The targets: unsuspecting United States Navy ships. With lightning quickness, the Japanese planes swoop in and deliver an explosive payload in a cacophony of sound and fiery fury.

BOOM! BOOM! BOOM!

The early-morning sucker punch ripped up eight US battleships. Four were sunk. And 188 aircraft were destroyed in a brazen attack the Japanese dubbed Operation Z. Worst of all: the sneak attack claimed 2,403 American lives.

For the Japanese, it was mission accomplished. The US never saw it coming.

Back in South Bend, Indiana, John Wooden listened on the radio to the reports and read the gory details in the newspapers. The nation raged over the attack. It ripped a hole in the heart of America. But it also galvanized the resolve of a nation — a result Japan hadn’t counted on. Until the “day that will live in infamy,” President Franklin D. Roosevelt had been reluctant to get involved in World War II, weary of the toll taken by the nation’s involvement in World War I.

But the Pearl Harbor bombing steeled the resolve of the nation behind the war effort, as America set its collective jaw to help defeat the Axis forces. There was no turning back. Any thought of remaining isolated from the war was finished. America was going to battle. And it was going to win. Like many of his contemporaries, Wooden was moved to do his part in the war effort.

At the time of the attack, Wooden was an English teacher and basketball, baseball, and tennis coach at South Bend Central High. Life was good. His career was on track. He had a house, an adoring wife, and a growing family with a son and daughter. Why give that up for the peril of war? Heck, he was 32, almost twice the age of some enlisted men.

Wooden joined the navy. He didn’t tell his wife, Nell. It wouldn’t have mattered what she said, anyway. Wooden was going to fight for his country. Period. End of story. He enlisted in January 1943 and was commissioned as a lieutenant. His job: get naval pilots in top physical condition.

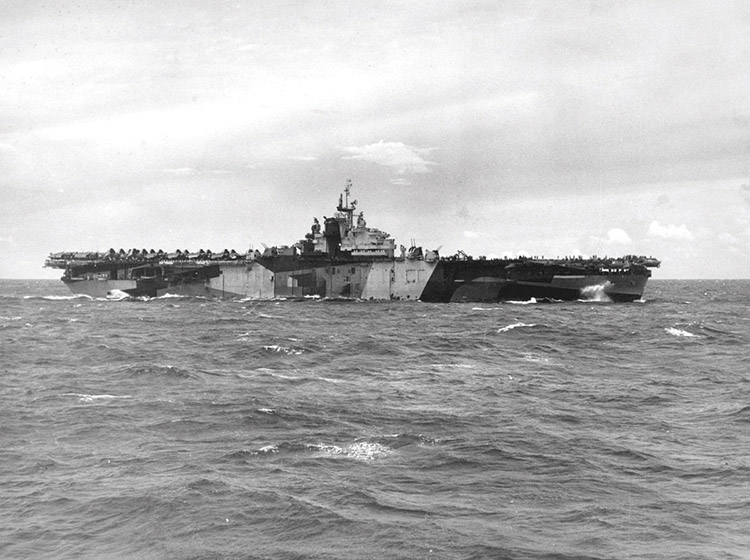

He began duty at the University of North Carolina, where he was prepared to enter the Naval Air Corps V-5 physical fitness program. From there, Wooden was sent to the University of Iowa, where he received his deployment orders to work aboard the aircraft carrier USS Franklin, also known as “Big Ben.”

Before deployment, he wanted to spend time with his family. It was one last time to say goodbye; one last time for a kiss and hug for Nell, his high school sweetheart; one last time to soak in what he was about to leave behind. That’s when it happened.

During the drive home, Wooden developed a pain in his abdomen. It was sharp and acute. What could it be? Once back in South Bend, Wooden saw a doctor who made the diagnosis: appendicitis. He needed surgery … now.

“Mom was concerned about Daddy,” says Muehlhausen. “She was happy he didn’t have to go aboard the Franklin, but she was worried about the surgery, too. It was a tough time.”

Navy procedures at the time required Wooden to recuperate for 30 days before joining a vessel that was headed for a combat zone. That meant the USS Franklin aircraft carrier would sail without Wooden in January 1945.

Lives Intersect

That’s when it happened. Fred Leon Stalcup Jr. got the call. Like Wooden, Stalcup was a fitness officer with the rank of lieutenant. Wooden had no idea until well after the war that a fellow Boilermaker and fraternity brother had taken his role aboard the Franklin. One Boilermaker replacing another. Neither could have known how their lives would end up unfolding because of that fateful switch.

Stalcup never flinched in boarding the Franklin. He was a tough guy, a former Purdue football player who strapped on a leather helmet for legendary coach Noble Kizer. Stalcup helped the Boilermakers go 14–9–1 from 1934 to 1936. He was one of two starting quarterbacks his first two seasons before playing linebacker his final campaign. He was good.

Like Wooden, Stalcup was moved to join the armed forces after the United States was sucker punched at Pearl Harbor. It was the right thing to do. It was the only thing to do. Every man in America wanted to do his part. That included Stalcup, who, like Wooden, was past 30 years old at the time he joined. Didn’t matter.

Stalcup spent time training at the Naval Academy. He also trained at the preflight training school at the University of Iowa as well as at the Naval Air Station in San Diego. He received his orders to report to the USS Franklin in December 1944. The ship’s deck log shows Stalcup came aboard on January 5, 1945. His service number: 142382. Stalcup listed his next of kin as his mother, “Mrs. Hallie B. Stalcup, N. Main Street, Bicknell, Indiana.” His primary duties were classified as athletics officer.

Stalcup was ready for duty. Stalcup was ready to serve his country. Stalcup was ready for war. But he had no idea what was about to unfold as the USS Franklin left port in Bremerton, Washington, on February 2, 1945, on the deep blue waters of the Pacific in support of an upcoming invasion of Okinawa scheduled for April 1.

On March 19, 1945, the USS Franklin maneuvered to within 50 miles of Japan. Think about that proximity to enemy turf. No US ship ever had gotten so close to the Land of the Rising Sun. That’s when Big Ben made its move, launching a raft of bombers toward the Japanese mainland.

BAM! BAM! BAM!

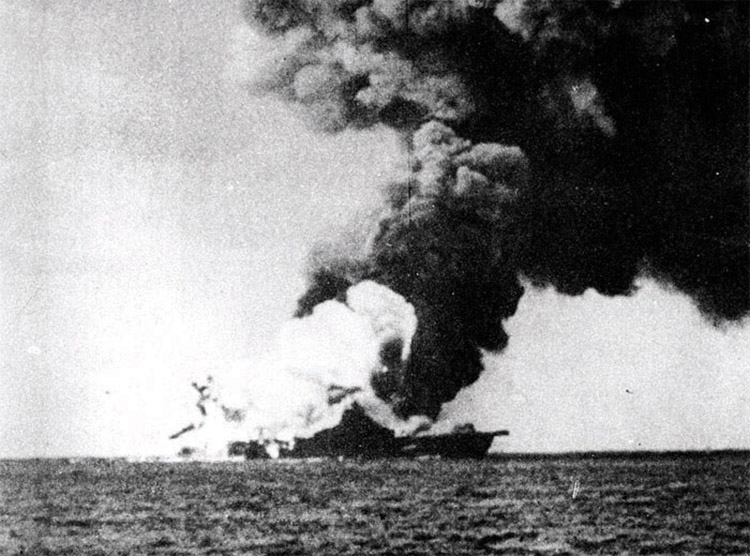

The sailors on the Franklin braced for a return hit. They knew it was coming. The wait is the worst part. Finally, it came. Hours later, a Japanese dive-bomber — either a Judy or a Val, according to reports at the time — dropped armor-piercing bombs. It was a devastating assault on Big Ben.

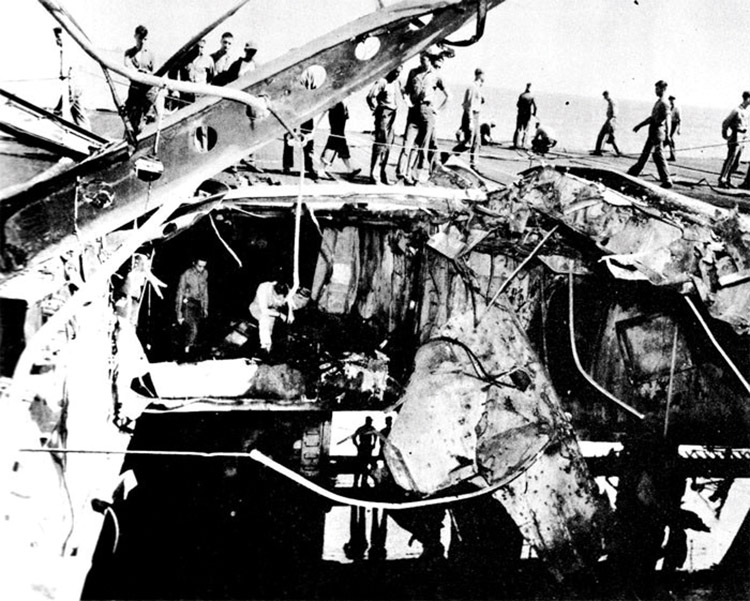

One bomb hit the flight deck and penetrated to the hangar deck. That caused massive destruction and sparked fires on the second and third decks. The combat information center was knocked out. A second bomb struck the rear of the ship, ripping through two decks. Later reports indicated they were 550-pound bombs.

The explosion on the hangar deck sparked fuel tanks on the planes, igniting gasoline vapor and creating an inferno that engulfed the deck. A five-inch gun turret was ablaze. Crewmen were blown off the deck of Big Ben by the explosion, screams piercing the black billowing smoke. Many men jumped into the roiling Pacific to avoid getting burned alive by the flames that danced nearby. The scene was a mixture of chaos, horror, and devastation. It was hell. And it wasn’t over.

The explosion caused perfectly aligned planes to cluster and jumble together on the flight deck above, setting off more fires and explosions while detonating nearby ammo. The massive USS Franklin was listing 13 degrees to the starboard side. She looked destined for a watery grave thousands of miles from American turf.

Unable to use radio communication and with fire raging and destruction abounding, the USS Franklin looked doomed. The admiral wanted to abandon ship, but the captain refused knowing many more men would be lost below deck. Survivors worked feverishly to save lives and to keep the massive ship afloat in the chop of the Pacific. There are countless tales of heroism on the carrier, stories of men who directed firefighting efforts and led rescue parties on board amid the din of destruction.

After six hours, the blaze was contained. The USS Santa Fe, a light cruiser, approached to take on the deceased and wounded. Five destroyers were dispatched to look for crewmen in the murky ocean waters. The USS Pittsburgh towed Big Ben to safety to Ulithi atoll.

Official navy casualty figures showed 724 killed and 265 injured. Over time, casualty numbers were updated to 807 killed and more than 487 wounded. The USS Franklin suffered the most damage and highest casualties by any US fleet carrier that survived World War II.

One of the deceased was Fred Stalcup. No one knows for sure how he perished aboard the USS Franklin. Did he jump into the vast ocean to avoid the unforgiving flames and drown? Was he burned alive? Was he blown up? It’s horrible to contemplate. This much is known: Stalcup died an American hero who gave his life for his country.

Stalcup paid the ultimate price. And Wooden never forgot it, making the most of his life. Following his discharge in 1946, Wooden went to Indiana Teachers College (now Indiana State) as athletic director and basketball and baseball coach. Purdue wanted Wooden to return to West Lafayette in 1947 as an assistant to Mel Taube and then assume command after Taube’s contract expired. But Wooden rebuffed the offer, saying he was loyal to Taube and didn’t want to make him a lame duck. Wooden moved on to UCLA and built one of the greatest dynasties in sports history. But if not for that case of appendicitis that caused him to miss his deployment …

“He talked about it,” says Muehlhausen. “It was in the back of his mind always. He did mention it fairly frequently. He hadn’t forgotten. It was there in his mind, and I think it always bothered him somewhat.”

Undying Gratitude

John Shively (M’78) shined a light on this remarkable story with a well-researched essay that served as the inspiration for this piece. Shively has written two books about war — Profiles in Survival: The Experiences of American POWs in the Philippines during World War II along with The Last Lieutenant: A Foxhole View of the Epic Battle for Iwo Jima.

Shively met with Wooden on Thanksgiving Day in 2005. Shively was with a group of well-wishers who had gathered at a small museum in Wooden’s hometown of Martinsville, Indiana, to honor the legend. Wooden was back home in Indiana for the John Wooden Classic in Indianapolis. Wooden’s undying gratitude was apparent to Shively on that day.

“The day I met Wooden, I asked him how he felt about the circumstances involving his war experience,” says Shively. “He didn’t say a word. He just pointed a finger toward the sky.”