Inside and ER

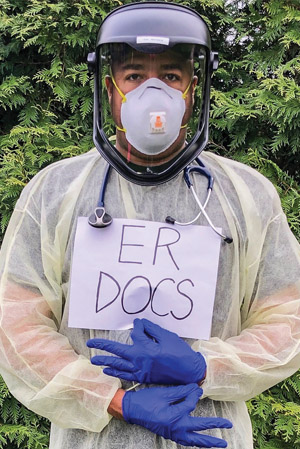

Michael McGee (BS’92) is the chief and medical director for the emergency medicine departments at Methodist Hospitals in Gary and Merrillville, Indiana. He also owns and practices at Premier Urgent Care Clinic in south Chicago. He is a member of the health and wellness committee and chair of the COVID‑19 committee for 100 Black Men of Chicago.

Initially, we were seeing our regular patients.Then, around the middle part of March, people started to come in with unexplained fevers, coughs, and flu-like symptoms but were testing negative for the flu. Even in December and January, we had people coming in with these symptoms, and we were like, “Man, I can’t believe that person was negative for influenza.” Because they had all the symptoms — fever, chills, body aches. We didn’t even think about it until later that those patients could have had COVID-19.

We started having more and more people come in with respiratory distress. The first thing you do is get a chest X-ray. People were having bilateral pneumonia, which is not very common. That’s characteristic of COVID-19 — ground-glass appearance. At first, we didn’t have the literature for proper treatment. We were intubating people and putting them on ventilators. We learned later that’s the worst thing to do. You do not want to intubate if you can help it because COVID-19 damages the lungs so severely it’s hard to get a patient off a ventilator.

In early March, I was exposed to several people, both patients and coworkers, who tested positive for COVID-19. Then I began developing bronchitis symptoms. Stay-home orders hadn’t even started yet. At that time, it was taking my hospital 10 days to get test results back. I didn’t want to wait. I went to three different places, waiting for hours before I was told they ran out of tests. I ended up going to Chicago, North Shore. Even though I’m an ER doc who had high exposure, I waited four hours to be tested. It came back negative two days later, which was beautiful.

We use one N95 mask a day, and we cover it with a surgical mask. Standard protocol would be to throw away your N95 after every use. Typically, use of N95s is rare — only if you suspected tuberculosis. So our stock was never that high. You throw in the fact that prices for N95s have escalated because hoarders bought them up and are selling them to make a profit. Hospitals are at a disadvantage. Everything was on back order from China. You’ve got a demand for equipment that is now extremely expensive. And you’re seeing fewer patients because nonessential surgeries and procedures are being canceled, and that’s how you make your money. You have to look at it from a hospital administrative standpoint. These things can make hospitals go out of business.

I bought my own welder’s mask. I wear that when I go into high COVID‑19 patient rooms. From a patient standpoint, it’s terrifying to be in that room, not knowing what direction you’re going towards — living or dying. You can’t see your family or friends. Now you can’t see the face of the person taking care of you. It’s our nursing staff who are most at risk. They are the ones who administer swab tests and medicines. They have much more contact with patients.

COVID-19 is as scary as you can see.It’s affecting people psychologically. People are concerned about their family, about spreading it to others. It’s depressing when you see all these people dying. Workers on the frontline don’t want to be around our families because we’re afraid of exposing them. I stay in the basement, away from my family, because I don’t want them to get infected.

Every so often, when I’m sleeping, I wake up sweating because I just had a dream that I’m surrounded by COVID-19 and I can’t breathe. I wake up like I’m suffocating. I’m not stressing about it because I am wearing the proper PPE, but my subconscious won’t let me relax enough to get good sleep.