An inside look at how this alumnus brought the democratic process to living rooms across the nation

George first saw Brian behind the wheel of what looked like a mobile hay wagon. As it pulled up to the Sigma Chi house, George realized it was instead a new beige Impala convertible draped with other new Boilermakers out for fraternity rush. They were all headed to the same Farm Frolics party.

George and Brian, who conspired with other friends to join Phi Gamma Delta, shared a passion for public affairs. George Sweet (IM’64) went on to develop some of Indianapolis’ most-livable, custom-designed communities, including the Village of West Clay. Brian Lamb’s path went to Washington, DC, where he founded a cable network, C-SPAN, which brought a firsthand look at public affairs to America’s family rooms.

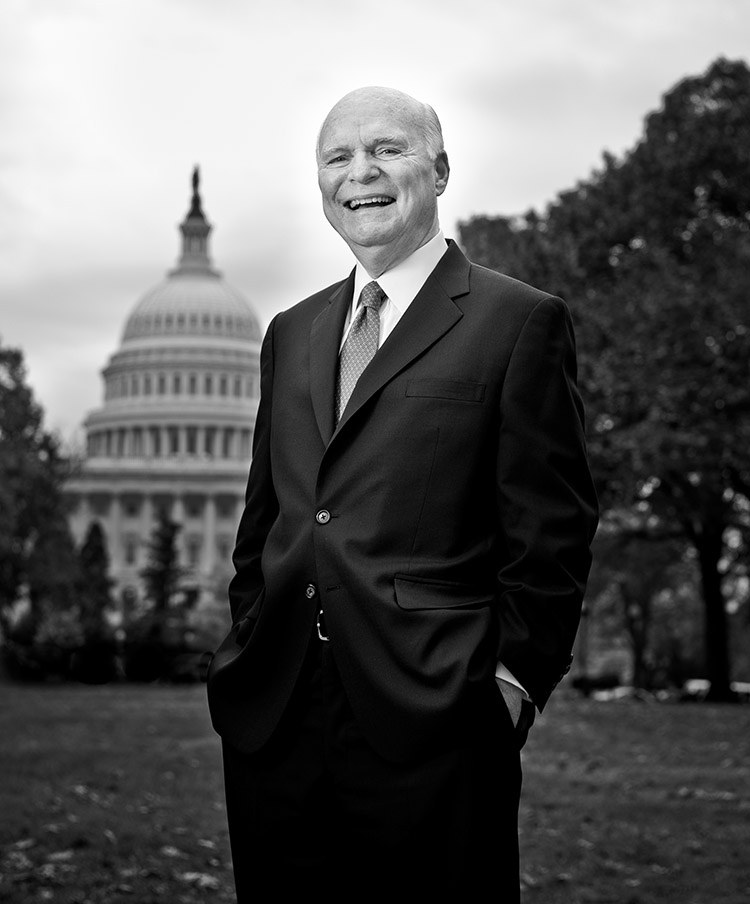

Lamb (LA’63, HDR LA’86), though, never forgot his Midwest roots and his alma mater. In 1987, he worked with David Caputo, then Purdue’s dean of the School of Liberal Arts, and Professor Robert X Browning to establish the C-SPAN Archives in West Lafayette. Now, 52 years after Lamb enrolled as a freshman, Purdue’s largest school in liberal arts has been named for him: the Brian Lamb School of Communication.

“It was an enormous surprise,” Lamb says. “When they called on me to say they wanted to name the school for me, I almost said, ‘You what?’ ”

In truth, he says, he didn’t have the most “imaginative” grades, except for classes in his major, speech, and he has always wished he’d done better academically. The son of a Lafayette, Indiana, beer distributor whose parents had never finished college, Lamb said academics hadn’t been a priority in his home. Instead of hitting the books at Lafayette Jefferson High School, he played drums in local bands and at age 16 was a disc jockey for WJEF Radio, signing on at 7 a.m. — before the sun was up and many of his classmates were just rising — for a show that reached only 100 feet outside the school doors.

In the summer after high school graduation, he started hanging around local WASK Radio. Owner Henry Rosenthal finally agreed to hire him to do odd jobs for $1 an hour. Later that summer Lamb made his first broadcast. It was just a station break — “This is WASK Radio, Lafayette, 1450 on your dial” — but it was on commercial radio.

Lamb eventually parlayed that into emceeing for WASK’s mobile unit at Columbian Park for a show called Summer in the Park and spent his college weekends working at the station eight hours on both Saturdays and Sundays.

In addition to working at WASK, he talked the manager of the local TV station, WLFI, into airing a version of ABC’s after-school dance program American Bandstand. Lamb was the host of the local show called Dance Date. Before anyone thinks that sounds glamorous, he sold the ads, built the sets, and recruited the dancers.

The money he earned helped put him through college.

Besides class and work, he also took part in Mock-P, which sent student delegates to a mock political convention at Purdue. As a Purdue sophomore in 1960, his convention team prophetically chose John F. Kennedy for president and Lyndon B. Johnson for vice president.

“Kennedy ended up addressing our convention by telephone,” says Lamb, who helped document the convention on film, providing the voice-over.

Lamb loved the mental weightlifting involved in the discussion of politics and government.

“Out of 75 or so in our fraternity house, he was one of two or three of us who read news magazines and discussed current events,” says Sweet, who would stay up late talking issues with Lamb.

Overall, Lamb says, “I was a doer, not an intellectual. But I’d always go the extra mile and never missed a class in high school or college. I hoped I’d get the benefit of the doubt by showing up.”

Purdue, however, opened his mind to philosophy, the sweep of history, classical music, and drama. In one theater class, he had the opportunity to serve six months as the rehearsal assistant to a famous contrarian playwright, William Saroyan.

“He was a writer-in-residence. Just being around him was fabulous,” Lamb says. “He wore all black, had lived in Paris.” He had won a Pulitzer for his play The Time of Your Life, which opened with its colorful characters in 1939, but turned the award down, saying art shouldn’t be measured by commerce. James Cagney later stared in the film adaptation.

Gregarious and curious

“You could pick Brian out of a crowd,” Sweet says. “He was a guy who knew where he was going and how to get there. And he knew everybody.”

Five-foot-nine with dark hair, often wearing class cords, Lamb was a sharp but conservative, button-down dresser. His gregarious personality helped him shake a lot of hands to win election as senior class president.

“We all went out to dinner the night before his graduation,” Sweet recalls. “It wasn’t late, but we decided to give him a night to remember before his big moment.” As senior class president, he was giving a speech at commencement the next day.

They took him to the Loeb Fountain in front of the administration building and tossed him in the water.

“I had a convertible with the top down,” Sweet says. “Afterward, everyone climbed on the back.” They’d gotten as far as the alley behind the fraternity house before the police pulled them over. The police flashlights never spotted Brian, who scurried through the bushes back to the Phi Gam house, his reputation saved for graduation day.

Besides being gregarious, Lamb also is widely known for his insatiable curiosity.

“He has a constant quest to know more information, and who’s behind the information,” says Sweet, CEO of Brenwick Development, who keeps in touch with Lamb weekly and sees him several times a year. “Socially, if you’re talking about something, chances are he’ll have an iPad in his hand and be looking up whatever is being discussed. He also has amazing retentive powers.”

Lamb remembers names like other people remember the days of the week and is always quick to acknowledge his friends and mentors.

The nation’s epicenter beckons

When he graduated from Purdue — right on time in 1963 after eight semesters — the draft was waiting. At his father’s encouragement, he kept his exemption and enrolled in law school at Indiana University Bloomington, hoping to put his speech degree to good use. The fit wasn’t right.

By the following June, he was an officer in the Navy, serving two years on the USS Thuban, an amphibious attack cargo ship deployed from its base in Norfolk, Virginia, to the Mediterranean Sea and the North Atlantic near Norway.

Hoping for an assignment at the Pentagon, he extended his tour of duty and in six months success followed persistence. He landed a position in the Navy’s Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs. There, he served as a public affairs specialist, which included time in Detroit during the 1967 riots.

As his Navy time in DC wound down, he aimed for something even more ambitious, a civilian job at the White House. A Lafayette friend was working for Sen. Birch Bayh, D-Indiana, who arranged for the interview that secured him a job as social aide to President Lyndon B. Johnson.

His time in the LBJ White House was like being a fly on the wall, watching the comings and goings of history. His duties included walking Lady Bird Johnson down the aisle at her daughter Lynda’s wedding to Chuck Robb in the East Room of the White House on December 9, 1967.

“Lady Bird was a tremendously important person in LBJ’s world,” Lamb says. “She was a straight shooter, his backbone, his center.”

He returned to Lafayette and found a job working for Dick Shively at WLFI-TV in 1968. However, the political scene still held its charms, and he was ready to jump back in.

With the help of a young Tennessee senator named Howard Baker, Lamb signed on with the Nixon-Agnew campaign and then moved on to gain an insider’s look at Capitol Hill as a press secretary to Sen. Peter Dominick, R-Colorado. From there, he joined the Nixon Administration as a midlevel aide — media and congressional relations assistant in Office of Telecommunications Policy. Then he moved on from government, writing as a journalist for the biweekly newsletter, The Media Report, and covering the cable industry as Washington bureau chief for Cablevision magazine.

Along the way, he took part in a little Washington intrigue.

“I’d had it with Watergate, and I left the White House in spring of 1974 to edit and produce the newsletter, making no money to speak of, maybe $500 a month,” Lamb says. But then his former boss at the telecommunications office, Clay T. “Tom” Whitehead, called on him.

Whitehead was a friend of Philip W. Buchen, who later served as White House counsel after Nixon resigned and Gerald Ford became president.

As Watergate came to a head, “Tom told Phil, you need to get Ford ready because Richard Nixon isn’t going to survive,” Lamb recalls. “You’ll need to prepare for the transition, identify the first 100 or so decisions Ford will have to make.

“Tom called together a team of four people to plan the Ford transition. We met secretly each week in his dining room in Georgetown. When the time came, we’d talked through the issues and created a loose-leaf notebook that was about an inch-and-a-half thick that we gave to Buchen. The morning Gerald Ford became president, Buchen got in a limousine, went to the president and handed him the book, saying ‘here’s an outline of decisions you need make.’ ”

Mosaic of experiences fall into place

Just as the planets had aligned for Ford, so too did they, in their own way, for Lamb.

Lamb had arrived at the White House Office of Telecommunications in 1971, just after Nixon’s “Open Skies” domestic satellite policy allowed private companies to launch communication satellites. Satellite transponders were becoming competitively priced, the cable industry was deregulated, and channel capacity was set to explode. In an age when many still used rabbit ears as TV antennas to improve reception, the nation was poised to leap into a revolution in telecommunications that spawned the modern cable industry and the hundreds of channels we know today.

The pieces of Lamb’s background fell into place. He had learned from Whitehead of the groundbreaking potential of satellites. He was fascinated with public affairs. He had been a fly on the wall at both the Johnson and Nixon White Houses and knew Capitol Hill. He had covered presidential campaigns. He had covered the cable industry — and he had a few contacts.

And fortuitously, at this same time, the US House was deep into a debate about whether to televise its daily sessions. Observing this, Lamb began to ponder: What if one were to transmit House proceedings without commentary, just set up a camera on the floor of the House of Representatives and transmit its proceedings into living rooms across the country via satellite?

He sold the idea to both Congress and the cable industry, making the case that it was a pubic service opportunity for the cable industry. Two cable leaders — Bob Rosencrans and Ken Gunter — put up the first $25,000 to seed the idea, and soon 22 other cable executives signed on.

Rarely called by its full name — Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network — C-SPAN was thus conceived in December 1977 and born in March 1979. It is a private, nonprofit company supported by cable and satellite affiliates, who today pay 6 cents a month per subscriber to carry C-SPAN’s three channels of programming.

It was the first “people’s channel” — letting viewers see government in action from their own perspectives and form their own impressions about what they saw. After starting with House coverage, the network was the first to regularly open its phone lines to allow citizens to talk directly to elected officials, political leaders, and journalists, as it still does today with its morning show, Washington Journal. Soon, Lamb’s team took C-SPAN on the road to cover presidential campaigns, political conventions, lectures, and history-in-the-making across the country.

It changed participatory democracy and trumped 20-second sound bites, providing a two-way window into the world of politics and government.

While political junkies turned to C-SPAN to feast on its marketplace of ideas, unfiltered by reporters, public officials began to find creative uses for C-SPAN. As president, Ronald Reagan watched C-SPAN to see exactly what his cabinet members said on The Hill. Politicians — Democrats, Republicans, and Independents alike, including Bill Clinton and Ross Perot — understood the value of C-SPAN telecasts to further their careers. Some say C-SPAN made Newt Gingrich, who used its gavel-to-gavel coverage of the House as a pathway to capture the Speaker’s gavel.

Lamb has been a regular on-air presence since C-SPAN’s beginning, interviewing every president since Nixon and many world leaders such as Margaret Thatcher and Mikhail Gorbachev. He was the host for the network’s series Booknotes (1989–2004), interviewing authors of more than 800 books — all of which he read.

His apolitical interview style has engendered a lot of teasing. He keeps his politics so private that no one can pin him down as a Democrat or Republican. When asked to identify Lamb’s political bent, Sen. John McCain, R-Arizona, in 1993 joked, “I think he’s a vegetarian.”

The formula — letting the news stand unvarnished by the reporter’s opinions — continues to work.

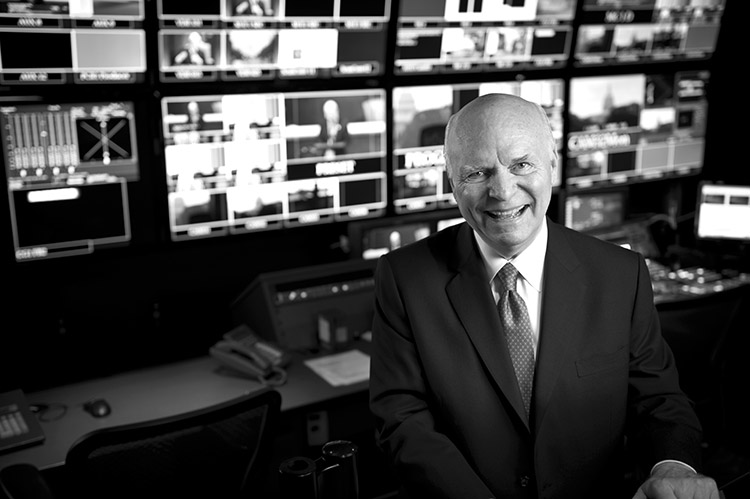

C-SPAN started with Lamb and three other employees in a 500-square-foot office. Now, almost 33 years later, it occupies 700,000 square feet a few blocks from Capitol Hill. It has three networks — its flagship channel that covers the House, one for the Senate and non-fiction books, and one for public affairs and history. C-SPAN also has 31 websites and one FM radio station broadcasting in DC and nationally on XM satellite radio. With a budget of $60 million, it has 275 employees and reaches about 100 million cable and satellite households.

Lamb, who lives with his Lafayette-raised wife, Victoria, in Arlington, Virginia, also makes sure that C-SPAN doesn’t focus just on the East Coast. He’s frequently in the Heartland, often in Lafayette-West Lafayette, where he introduced his C-SPAN crew to the former legendary Stiney’s Restaurant on the Wabash and an Indiana catfish experience. He’s been back on campus numerous times to talk to students, formally spending time with them as an Old Master in 1983 — “I really love that program” — and was awarded an honorary degree in 1986.

This September, he interviewed Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels in Fowler Hall. That evening, he was honored at a dinner at the Dauch Alumni Center, where a bronze plaque was unveiled bearing his likeness. Commissioned in his honor by staff at C-SPAN, the plaque now greets visitors as they enter the main office of the school named in his honor.

Lamb has ratcheted back some, but at age 70 he is still on-air as host for C-SPAN’s Q and A, an hour-long program on Sunday evenings with people at the forefront in politics, media, education, and technology. He says he has no plans to hang up his microphone any time soon.

Asked for his advice to students, Lamb — the man known for his curiosity — says, “Don’t ever stop asking questions. It will pay off for you.

“And don’t ever turn your back on your university. It is so rewarding to be involved with your school as you get older. We had a saying at the fraternity house that fraternities are not for college days alone. You could turn that around and say college is not for college days alone. There is so much value in staying connected.”

C-SPAN Archives

The C-SPAN Archive captures modern American history.

The archive was created and is directed by Purdue Professor Robert X Browning. It has had a relationship with the university since 1987, formerly with an on-campus location and later, as part of C-SPAN operations, located at the Purdue Research Park.

Now with 165,000 hours of content and still growing, the archive is available free online in a digital format. It includes presidential speeches, sessions of Congress, Congressional committee hearings, campaign speeches, and more. About 115,000 individuals are indexed. The site averages 30,000 views a day, but some days it climbs as high as 350,000.

Teachers, scholars, students, and historians were the intended users. Staffs of political campaigns and parties also have found it handy for documenting the opposition’s position on issues across time. What’s been said on C-SPAN for the last 24 years is all on-the-record, which occasionally has led to headaches for some political figures such as Vice President Joe Biden and Christine O’Donnell.

The footage is cited in campaign ads, blogs, and news reports. The TV series The West Wing and The Real Housewives of D.C. used C-SPAN video to create realistic scenes.