Almost from the moment of its founding, Purdue University was home to tales so strange that they seemed to be the stuff of legend, not real life. Was founder John Purdue really so particular about the appearance of campus that he insisted that no building be taller than University Hall? Did he demand that no foreign languages be taught at the university?

Over time, the university’s mythical tales multiplied. Does the university really have space-born trees growing on campus, marijuana plants thriving in research labs, and a nuclear reactor humming along in a secret basement?

We decided to find out the truth. From tour-guide tall tales to legends that have been passed down for generations, we examined many of the most common myths about Purdue, then sleuthed our way through archives, called up the most knowledgeable experts on campus, and got down to the bottom of these mysteries.

The truth is out there, and we’re happy to bring it to you in these pages. Got another Purdue-related mystery you’d like us to solve? Contact us at [email protected].

The Very Tallest Tale

The claim: John Purdue demanded in his will that no building be taller than University Hall.

The reality: Neither historical evidence nor today’s reality can back up this assertion.

A quick study of Purdue’s campus shows that University Hall, while impressive, isn’t the tallest — or even second-tallest — building on campus. Those honors go to Beering Hall and the Mathematical Sciences Building.

So is the university deliberately thwarting the wishes of the university’s founder?

David Hovde, an associate professor of library science who works at the Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center, says this claim is a clunker. “First, John Purdue did not leave a will,” he says. Then he ticks off all the other places where the founder could have — but failed to — make such wishes known. “There is no documentation in any form that mentions this. It’s not in the Board of Trustees minutes, documents concerning the establishment of the university, nor the annual reports of the president.”

While elaborate theories have been concocted about how the two tallest buildings might technically fulfill Purdue’s nonexistent wishes (Beering’s top floors have a different zip code, nullifying it as a “campus” building, while the open space beneath the Math Building qualifies it as a “bridge,” not a building, the reality is that no such loopholes are necessary.

Weeded Out

The claim: Purdue grows marijuana plants.

The reality: What, are you high? Though it’s technically true, you definitely won’t find any of the mind-altering plants growing under researcher supervision.

Drive 16 miles southeast of Purdue’s main campus to the Throckmorton Purdue Agricultural Center, and you’ll find a couple acres of spiky-leaved plants growing in tidy rows, some of which reach a full 16 feet in height.

But if you think you’ve reached some sort of marijuana nirvana, think again, says agronomy professor Ron Turco. “Those plants are Cannabis sativa,” he says. “It’s marijuana that contains less than 0.3 percent THC, which is the chemical responsible [for marijuana’s psychological effects].”

You might not be able to put it in your pipe and smoke it, but the plant — which can be used to produce industrial hemp — has plenty of benefits. The plant’s fibers are ideal for rugged-use clothing items, including jeans and shoes, and they can be an excellent substitute for fiberglass. The seeds, high in protein, calcium, and iron, can be used as dietary supplements. And its oil has been floated as a potential biofuel.

Currently, Turco and others study how the plants grow, how they’re affected by insect and disease, and how they can be best harvested. They’re also working with hemp growers to strengthen their businesses. “There are a lot of market opportunities, so we’re trying to help growers develop them,” says Turco.

That said, the plant’s association with the popular drug causes its fair share of hassles, Turco says. Because the two plants are virtually indistinguishable to the naked eye, growing industrial hemp requires multiple permits and registrations.

Still, it’s easier than landing a federal Schedule I permit, which would allow the university to grow the THC-containing plant. “For that, we’d have to grow it indoors, people would have to have background checks, we’d have to have multi-pass key cards — the security required would be enormous,” he says. “And because nobody really supports research on it, I’m not sure how you’d pay for it all. I don’t see it happening anytime soon.”

The Story of the 17 Steps

The claim: The 17 steps leading up to Haas Hall were designed to memorialize the lives of 17 people, including 15 Purdue students, who were killed in a train accident.

The reality: The building, not just the steps, keeps their memories alive.

On October 31, 1903, there was a horrific trainwreck — caused by the inattention of a train dispatcher — that killed 15 Purdue students and two people unaffiliated with the university. Eleven of the students killed were football players en route to a game against Indiana University.

In memory of these men and women, Purdue decided to build Memorial Gymnasium in their honor. In 1908, the building opened for use. One of the best athletic complexes of the time, it contained a swimming pool, gymnasium, overhead track, and trophy room. Though the building does have 17 steps leading to the entrance — 11 steps, a landing, then six more steps — no documentation exists that suggests that this feature was specifically designed to recognize the 17 people who lost their lives in the accident, says Hovde.

The building has since been remodeled, and it currently houses classroom, office, and laboratory space.

What a Blast

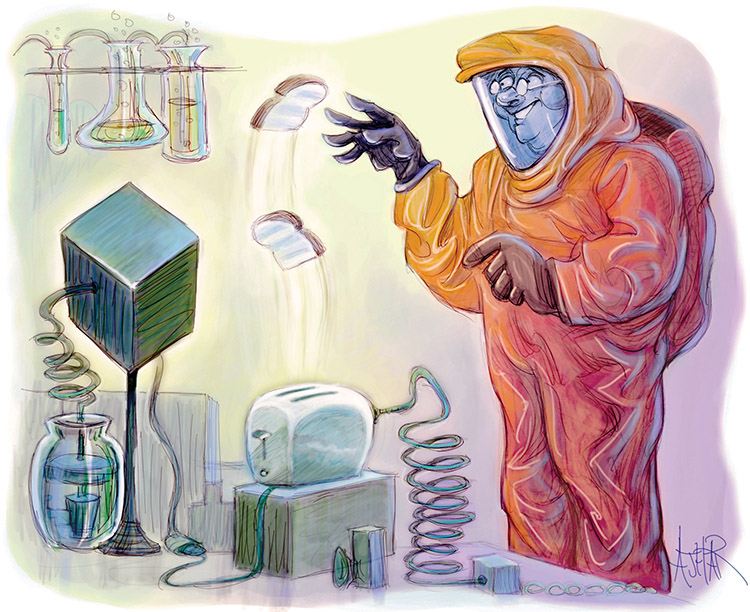

The claim: There’s a working nuclear reactor on campus.

The reality: The explosive truth? It’s for real.

If there’s one thing that mystifies Robert Bean, assistant professor of nuclear engineering and director of the radiation laboratories, it’s how the school’s nuclear reactor — which has been up and running since 1962 — retains its mythical status. “We have a web page about it, and I give public tours to a few hundred people every quarter,” he says.

While the reactor is anything but secret, Bean admits that it’s so much more modest than what most people imagine when they hear the words “nuclear reactor” that it’s easy to overlook.

The Purdue reactor, a cube that’s roughly two feet per side, and which sits at the bottom of an eight-foot-diameter pool, produces a maximum of 1,000 watts of heat.

Sound like a lot? It’s only enough to power a toaster. “The only way the fuel in our reactor would be dangerous is if you took the reactor itself and pounded someone over the head with it,” Bean jokes. Nonetheless, there are multiple safety systems in place to prevent and control any potential accidents.

While having a reactor on campus is rare — indeed, it’s the only working reactor in the entire state — the benefits are myriad. The nuclear engineering program has more than 175 undergraduate and graduate students who get hands-on experience with the reactor; the reactor is also appropriate for a variety of deeper research projects.

One inaccurate story Bean has had to refute is that the fountain outside the engineering building is the cooling tower for the reactor. He dismisses it handily. “Well, for one thing, you don’t need a cooling tower for 1,000 watts,” he points out. “And for another, the reactor was built 17 years before the fountain was.”

Bean says he also had to explain to someone that the reactor was not a top-secret backup power plant for campus in case of emergency. “I only got that question once,” he says. “But I’ve been making fun of it ever since.”

Moving the Goalposts

The claim: After rowdy fans uprooted the goalposts after victories at Ross-Ade Stadium, the university installed specially designed goalposts that are impossible to remove.

The reality: The installation of “indestructible” uprights is true — but it’s only one part of a larger set of strategies and tactics that the university uses to keep the goalposts in the ground for fan safety.

In 1992, Purdue’s first football game of the season was against the University of California, ranked 17th in the nation. Purdue, to put it charitably, was not expected to fare well against one of the country’s most competitive teams.

But when the Boilermakers trounced the Golden Bears 41–14, a jubilant crowd stormed the field. Steve Simmerman, senior associate athletic director, remembers the day clearly. “They broke the goalposts off, carried them out of the stadium to the Main Street bridge, and threw them into the river,” he says.

While Simmerman understood the enthusiasm, he and other officials at the university were rightly concerned about student safety. “There’s a lot of metal, a lot of weight, and when those things come crashing down, there’s a good chance that someone could get hurt,” he says. Indeed, across the nation, dozens of students have been seriously hurt by students rushing the field and tearing down goalposts.

It happened again in 1996. Purdue stunned No. 9 Michigan in a 9–3 upset. Fans ripped down the north goal post and tossed it in the Wabash River. Not long after that incident, Purdue did install goalposts from a Chicago-based company that guaranteed that they were indestructible, complete with a 10-year warranty.

Students put the posts through the wringer: Simmerman says that they were tested multiple times during the following five years, but they stayed put.

While the goalposts are considered among the safest ever developed, Purdue has also implemented an array of other tactics and strategies to ensure they stay that way, including greasing the posts and working closely with university security to ensure that fans don’t enter the playing field.

The goalpost challenge even became a class project: in 2002, ESPN published a story on a mechanical engineering class led by Bill Szaroletta, who was then an assistant professor at the university. He asked his students create other safe goalpost designs for universities to consider.

Simmerman, for his part, wants readers to know that the university’s ultimate goal isn’t to be a buzzkill. “I know that some people think of [uprooting the goalposts] as a challenge,” says Simmerman. “But we don’t protect the posts because we think they’re sacred and don’t want them torn down. We just everyone to stay safe.”

A Far Out Forest

The claim: There are trees from space on Purdue’s campus.

The reality: They may not seem otherworldly, but there are indeed multiple trees that got their start outside of our planet’s atmosphere.

Trees aren’t exactly known for their globetrotting ways, but five trees on Purdue’s campus have a pedigree that puts even travelers with fully stamped passports to shame.

As part of a research experiment in 1984, a group of sweetgum seeds were germinated in space. Of these seedlings, five were donated to Purdue by Charles Walker (AAE’71), who was an astronaut on the shuttle. “The trees were planted in a tree nursery on campus until they were large enough to relocate to more permanent locations on the West Lafayette campus,” says Purdue’s lead arborist, Tim Detzner. “During that time, they were given the name ‘shuttle gums’ by a grounds staff member.”

Four of the trees survived, and can be found at the northwest corner of Grissom Hall, the northwest corner of the Mechanical Engineering Building, the northeast corner of Forney Hall, and at Pickett Park.

Four years later, Purdue added a fifth tree with outer space on its résumé. The sycamore seedling, which was donated by astronaut Jerry Ross (ME’70, MS ME’72, HDR’00), now calls the north side of Lilly Hall home. It’s a robust 14 inches in diameter.

Despite their unusual histories, the trees are no divas: they get the same care as all the others on campus. “These trees are checked and maintained on a regular basis as part of the campus tree care plan,” says Detzner.

Truth That’ll Blow Your Mind, Man

The claim: Purdue’s researchers synthesize LSD and ecstasy in their labs.

The reality: Back in groovier days, Purdue researchers did synthesize the compounds that create the hallucinogenic effect in our brains. Today, the university’s researchers stay on the straight and narrow. Squares.

It’s been a long, strange trip. For more than three decades, David Nichols, emeritus professor of pharmacology at Purdue, was known as one of the world’s top experts in the chemistry of psychedelics.

During the course of his career — he arrived at Purdue in 1974 and moved to emeritus status in 2012 — he studied the Way these compounds affected the brain, and the corresponding changes in behavior.

To study these effects, his lab, with the appropriate permits, did synthesize the chemical compounds found in drugs including LSD and MDMA. The research has plenty of practical implications: Such compounds have been thought to have promise for people suffering from anxiety and terminal illnesses.

And while there might have been plenty of student volunteers for these studies, Nichols’ research subjects were rats. “He certainly was not doing any clinical studies, where the drugs were administered to people,” confirms Eric Barker, associate dean for research in the College of Pharmacy and a professor of medicinal chemistry and molecular pharmacology.

As for Nichols’ personal experience with the compounds? He remained coy. In a 2012 interview with the publication Erowid, he said only: “I suspect I’m much less experienced than people might imagine that I am.”

When Nichols wound down his research program, the university’s work linked to the hallucinogens ended, too. “Every faculty member has their own specific research interests, and when Nichols retired, that area of research went with him,” Barker explains. “But the myth continues to be propagated for a new generation of students.”

Myths Put to the Test

Some myths earn their status from the unconfirmable depths of history; others are superstitions whose truths are put to the test regularly. To learn more about those in the latter categories, we decided to go straight to the students and alums who could share their experiences — and their results.

The myth: If you kiss someone beneath the Bell Tower, you will marry that person.

Field test #1

Cierra Perry graduated in 2015 with a BA in law and society. Joshua Wilson is slated to graduate this spring with a degree in agribusiness management.

Cierra: I come from a long line of Purdue graduates. I am very familiar with, and believe in, Purdue myths and superstitions.

Joshua: The myths never really bothered me, but I knew I was going to ask Cierra to marry me underneath the Bell Tower. It was nerve-wracking not just because I was asking her to marry me, but because I also worried that she wouldn’t walk under the Bell Tower with me because I hadn’t graduated.

Cierra: I was genuinely upset that he had risked the superstition!

Joshua: I had placed roses underneath the center of the Bell Tower. When we approached them I got down on one knee and asked her to marry me. She responded with an astounding yes, and we kissed.

Cierra: The Bell Tower holds such a special place in my heart. We will always remember getting engaged under it, as well as having my sister there to photograph it.

Joshua: Cierra and I are planning on getting married this October! And long as this semester plays out accordingly, I am on track to graduate this May, in four years.

Cierra: And I can’t wait to walk my own children around campus one day and teach them the same myths that were taught to me.

Field test #2

Brad Joyce graduated in 2008 with a degree in building construction management. He married Christine “Petey” (Vidimos) Joyce, who graduated in 2008 with a degree in management.

BRAD: My first kiss under the Bell Tower with my wife, Christine, was the night I proposed. I didn’t feel worried about the myth because I wasn’t aware of it. It was mid-February 2010, and it was zero degrees, so mostly I felt cold. I was ecstatic when she said yes.

We got married on June 4, 2011, and every time we see the Bell Tower, we are reminded of that cold February night.

Field test #3

Julianne (Debald) Reichenbach graduated in 2009, and her husband, Randall Reichenbach, graduated in 2008.

JULIANNE: My husband and I met in class, had many walks together through campus, and yes, shared some kisses beneath the Bell Tower. Am I superstitious? I wouldn’t say so, but that doesn’t mean I’m not willing to do something that might help a situation. We’ve been together for eight years, and have been married for four.

Field test #4

Kayla (Wigginton) Fox graduated in 2013, and her husband, Ian Fox, graduated in 2012.

KAYLA: Ian and I went to my senior formal. While walking to my sorority house to get on the bus, we stopped under the Bell Tower. We said “I love you” for the first time and we kissed. We’ve been married two and a half years, and now have a beautiful and healthy baby girl.

The myth: The seal beneath the Bell Tower is cursed. Step on it as a student, and you don’t have a chance to graduate in four years.

Field test #1

I definitely knew not to walk under the tower if I wanted to graduate on time. I’m not normally superstitious, but didn’t want to test my luck with the storied Bell Tower.

Brad Joyce (T’08)

Building construction management

Field test #2

I walked under the Bell Tower all the time before hearing about the four-year myth. I graduated in 4 1/2 years. I’m sure my having to retake statistics and differential equations had nothing to do with it!

Meredith Sears Kinkle (CE’05)

Civil engineering

Field test #3

I walked under the Bell Tower as a freshman in 2006. I changed my major four different times, but still graduated in four years.

Carolyn (Jones) Banik (LA’10)

Communications

Tour Guide Tall Tales

We asked a couple of tour guides to tell us some of the stories they tell prospective students on tour, then we did the due diligence to find out if the stories are true.

I like to tell people that we have professional scuba divers come and clean the inside of our university water tower. They wear their full gear to do so.

Songa Ruganzgazi

Industrial Engineering

Is it true? Yes! Every other year, a diver in a sanitized dry suit clambers into the 1.5-million-gallon tank to clean and inspect it.

I’ve heard that the clock face on the Bell Tower uses the roman numerals IIII instead of IV for the number four because “IV” looks too much like the initials of our rival, IU. But, I explain that the real reason is that it makes the clock face more symmetrical when IIII is across from the VIII.

Julia Bergmann

Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences

Is it true? Though it’s difficult to say definitively, it is true that a significant percentage of all clock faces with roman numerals swap out IV for IIII. So aesthetics or not, there’s no reason to believe a sports rivalry was the cause.

Setting John Purdue’s Record Straight

As Purdue University’s primary original benefactor, John Purdue wanted nothing more than to help build a strong university in Indiana, and he attached relatively few strings to his at-the-time massive $150,000 gift. But perhaps it’s true that no good deed goes unpunished: the dubious claims about his life, his demands, and his final resting place are so vast they could fill the historical equivalent of the TMZ gossip site. To help get to the bottom of some of these myths, we talked to associate professor of library science David Hovde. Armed with an archive full of data, he gave us the not-so-dirty truth about Purdue’s founder.

Is John Purdue actually buried on campus? Or was his body moved to an alternate location because of student and rival pranksters who tried to dig him up?

No. He was, and still is, buried in front of University Hall.

Did Purdue demand that no foreign languages be taught at the university?

No. In fact, Purdue was in attendance when the Board of Trustees assigned John Hussey as the chair of Latin and modern languages in 1875.

Was Purdue the one who decided the school colors should be old gold and black?

Probably not. That decision was most likely made in 1887 by John Breckenridge Burris, a junior football player at Purdue. The newly created athletic team was scheduled to play Butler, but had no official team colors to wear at the game. At a hastily convened meeting with faculty and students, Burris suggested orange and black as a nod to Princeton, an athletic powerhouse. The committee was eager to be a bit more distinctive, and modified orange to old gold. According to one source, the final decision was made in three minutes.