Life is made up of an infinite number of choices. Many are mundane, but the more difficult decisions have the power to transform us, helping us lean into a bigger life. Platitudes like “choose the road less traveled” make those big decisions — true turning points in our lives — seem simple and exhort us to just go for it. After all, what do we have to lose?

But the decisions that lead us down paths that are potentially life-changing can be overwhelming and sometimes paralyzing. We often want to play it safe — and we rarely make these decisions easily. Ultimately, though, making a choice that may lead to a more fulfilling life allows us to be the creative force in our own experience.

Here, Boilermakers share the moments when they chose a bigger life, including the sacrifices or challenges they faced along the way.

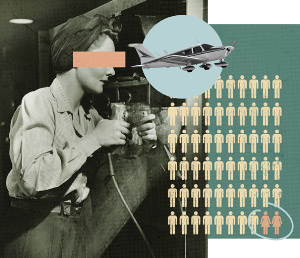

I refused to listen to “girls aren’t allowed to do that.”

Faith (Wayne) Pearson (S’43) is 96 years old and lives in Newington, Connecticut.

Starting out: My dad taught me that I could do anything. I wanted to be an engineer, but that path was frowned upon for women, so I enrolled in a new program at Purdue called “The Special Science Course for College Women,” which included physics and abstract math and allowed us to study engineering on the side. On a dare from my older brother, I applied and got one of two token spots for girls at Purdue’s Civil Aeronautics Association flight training program, which also included 58 male students. My brother was rejected because he didn’t have 20/20 vision.

Persistence pays off: I soloed after seven hours of training and passed my pilot’s license test with 35 hours in the air, a new record at the time. Because I wanted to own a plane and know how to fix it, I cleaned parts and pestered the mechanics with questions.

When impossible isn’t: I wasn’t “allowed” to do a lot of things in my lifetime, but I did them anyway. I bought a house (with a letter from my male boss) after my divorce, and I worked as an engineer designing airplane blades at Hamilton Standard Propellers. I had to leave the job in 1944 before my first son was born because women weren’t allowed to work and be pregnant at the same time.

Because shuffleboard is for suckers: In 1989 after family life and a varied career, including starting my own management information systems company, I returned to Purdue to renew my pilot’s license when I was 67 years old. I bought a Piper Cherokee 235 and starting flying again.

I moved across the country to earn an MBA.

Randall Herrel (AAE’72) is president and CEO of the Catalina Island Co. in southern California.

When your best isn’t enough: My first job after college was as an aeronautical engineer at McDonnell Douglas. We designed a DC-10 that was highly fuel efficient and frankly better than our competitor’s, but Eastern Airlines bought their plane instead of ours. I didn’t understand — why buy an inferior product? My supervisor told me that our competitor gave Eastern a favorable lease agreement even though we had a better-performing plane.

Tunnel vision: I realized my view of how the world works was too narrow. I’d never considered all aspects of a business: finance and marketing. My vision at that point had been about engineering the best airplane.

California, here we come: That eye-opening DC-10/Eastern Airlines moment awakened a desire to broaden my understanding of the big picture. I was accepted to Stanford University’s MBA program, so my wife and I piled everything into our car and moved to Palo Alto, California, leaving behind everyone and everything we knew. It was with mixed emotions — excitement and fear — that we headed west.

A new way to think: The combination of engineering and business degrees trained me to think outside of the box. Looking at the total picture of a company — from design to operations —has become second nature. As a CEO, being responsible for improving an entire company’s performance has been fulfilling and rewarding. In choosing a bigger life, my best chance for success was earning engineering and MBA degrees.

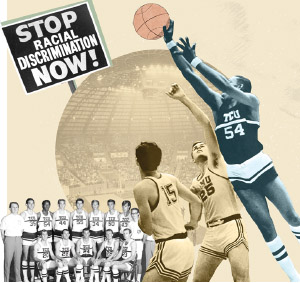

I crossed racial barriers.

James Ireland Cash (MS S’74, PhD M’76) is a professor emeritus and former senior associate dean of the Harvard University Graduate School of Business.

Breaking the color line: I grew up in a segregated community in Fort Worth, Texas. In 1965, I became the first black player to accept a basketball scholarship in the NCAA’s Southwest Conference at Texas Christian University. I was ready to handle the challenges and contribute to the major social revolution of the time — the civil rights movement. I knew the position came with responsibility and the need for thick skin. Occasionally, I needed police escorts to enter and exit arenas. Referees called cheap fouls on me to get me out of the game. I never let racial slurs and discrimination penetrate my psyche — it wasn’t in my makeup to let that affect me.

Life beyond basketball: I had developed a valuable but narrow and shallow perspective growing up in a segregated environment. TCU taught me about other people and places, including religious, ethnic, and racial groups that I previously didn’t know existed. My college education led to a job at historically black Langston University, then to higher degrees at Purdue, then to becoming the first black tenured professor at Harvard Business School.

Belief system: Romans 5:1–5 conveys that we should rejoice in our tribulations, as every path has a purpose that, though we may not understand it in the moment, will be revealed later. “You cannot discover new lands unless you have the courage to lose sight of the shore” is a quote that I’m committed to by self-imposing term limits on how long I’ll live and work in a single place.

I saw opportunity beyond my hometown.

Melody Birmingham-Byrd (T’94) is president of Duke Energy’s Indiana operations, the state’s largest electric utility.

Home is where the heart is: I grew up in Chicago, the youngest of seven children in a Christian and supportive home. I knew that I could be content in that world, but I also knew there was life beyond Chicago, and I wanted to pursue that life. I grew up in a family that had a strong work ethic, and I anticipated that Purdue would be challenging, so I buckled down on academics and the jobs that helped me pay my way through college. My mother was a great example and I wanted to make her proud. I planned on a career in accounting or law.

Called to lead: I soon discovered that my passion was in leadership. My first experience was as freshman board president in my dorm and then later as the manager of a temporary employment agency — all while I was attending Purdue full time. I began appreciating the importance of effective leadership after growing up hearing my mother discuss the shortcomings of management in her manufacturing workplace. Her experience led to me to pursue a degree in organizational leadership and supervision, which provided me tools to become a more effective leader.

Leading by example: Since leaving home for college, my career has required me to move away from family and friends numerous times to pursue my professional goals. Leadership has come with other challenges and responsibility. As a young African American female who has had roles of increasing responsibility, I’ve held myself to a higher standard in hopes that my track record could help build a bridge for others to cross.

I left a great job to start a new business.

Stephen Can (MS M’84) is a Blackstone senior managing director and cohead of Strategic Partners Fund Solutions.

When life is good: I worked at IBM for 16 years. Near the end of my time there, I was comanaging — with a great partner and mentor — a $5 billion private equity portfolio for the company. I loved the job. As I was selecting private equity funds for IBM to invest in, I was learning from people pitching really smart ideas for great returns at low risk. I walked to work from our home in Stamford, Connecticut. I coached soccer. There were golf courses nearby. We had great friends.

Opportunity knocks: When the Wall Street firm of Donaldson, Lufkin, and Jenrette approached me about starting a specialty private markets business in secondary transactions, saying yes was risky. My wife, Pam, said you don’t want to later wonder, “What if?” so we put every dime we had and more into this startup. I commuted to New York. I worked at high stress most of the time; 9/11 happened about a year later, and then the dot-com bubble burst.

The payoff: It’s turned out much better than I ever imagined. Today we’re a Blackstone-affiliated business with 1,100 completed transactions. We’ve raised $31 billion in capital. But more importantly, we’ve built a team of people who are really smart and team oriented. I can focus on giving back by funding scholarships for students at the community college I attended.

I found ways to improve prisoners’ lives after my brother’s incarceration.

Alec McGail (S’14), the founder of CheckIt Publications, is a PhD candidate in sociology at Cornell University.

Behind bars: My brother was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 2014. He has access to information because we have a very nice mother who sends him whatever he wants. But he noticed that other prisoners don’t have people on the outside wondering what they like to read. We started talking about how to give inmates automated, customized content.

The idea that stuck: I was learning about new technologies and big data at a programming job while considering potential startup ideas. Mechanizing my mother’s services for other prisoners made the most sense, so I quit my job and took two years off to develop CheckIt Publications.

Paper products: It’s cheaper to send magazines of unlimited pages to prisons than it is to send letters, which are limited to five sheets of paper. I built algorithms to render and print 40- to 50-page personalized editions of interest to prisoners, including Wikipedia articles, literature, photographs, puzzles, and flashcards. I have about 12 subscribers, and it costs them $10 a month. Getting customers is tough because my target audience is in jail and prisons don’t like to put up a flier. I’m working on attracting benefactors to pay for subscriptions, but I may have to take a break from growing the business to concentrate on school for a while.

Learning curve: My views about incarceration and rehabilitation have evolved. I believe inmates should have access to the internet. I also discovered I can be self-motivated without the need for external approval or stimulation.

I learned to fly.

Capt. Donna (Boyer) Beering (T’86) flies the Airbus 319/320 for United Airlines.

Raised on Star Trek: That show sparked the dream of flying for me. I remember watching a supersonic bomber land at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base from atop my dad’s shoulders in 1973. It looked like a swan flying through the air. It was white, loud, and beautiful. I thought, “I’ve gotta do that.”

The truth hurts: My first job after earning an aviation technology degree was as a flight instructor at the Purdue airport. I’d been happily working there for two years when a good friend pointed out that I was complacent and going nowhere. When I quit crying over his harsh words, I was left with two unavoidable truths: He was right, and I was the only person who could do something about it.

Full steam ahead: The next day, I drove three hours to Dayton, Ohio, and applied for a pilot’s job with a small airline, Jetstream Piedmont Commuter. I was hired on the spot. Ten days later, my career started. All I’d had to do was knock on the door in front of me rather than waiting for an opportunity to find me.

Up in the air: Taking action on my own behalf that day quickly led to becoming a pilot for United Airlines, which hired me only 11 months after I began flying for Piedmont. I’ve flown domestically for United for nearly 30 years now. Prior to my first flight, I’d never been west of the Mississippi River, so flying has opened the world to me. That being said, I made the decision to value seniority and control my schedule for my family’s sake. I chose to be the pilot of a smaller airplane to have holidays off, as well as regular weekends at home. That’s been important to me.