Black Cultural Center celebrates 50 years of embracing diversity

Folks you’d better stop and think.

Everybody knows we’re on the brink.

What will happen, now that the King of love is dead?

Three days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Nina Simone and her band debuted “Why? (The King of Love Is Dead)” in New York. Written in reaction to King’s death, the lyrics reflect emotions felt across the United States — grief, anger, disbelief, and fear.

Students on Purdue’s campus were no exception. As the campus reeled, students met in a sorority house on Stadium Avenue to decide how to react.

“Everyone on campus came out,” recalls James Bly (M’89). “We had this meeting, and there are the vocal leaders like Eric McCaskill (LA’69, MS M’71) who played football, ran track.”

Their participation was critical.

“The athletes coming off the Rose Bowl, they were the ones who gave our demonstration legitimacy,” Bly says. “They were risking everything. They could’ve been kicked off the team because they were demonstrating.”

While the athletes provided credibility, Bly added foresight. The next day, as a silent march of protest began, he hung back. “I went back to my roommate, who was a white fifth-year senior, and I borrowed his Plymouth Belvedere. Everyone asked me what I was doing. I said, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll be behind you.’” Bly followed the protesters in the Belvedere. His foresight paid off. “A guy drives up behind us and is vociferous. He was angrier than people can believe,” recalls Bly. “We continue, he gets frustrated and turns back.”

Bly’s quick thinking repelled first one, then a second vehicle — the drivers of both were angry and verbally abusive toward the protesters. “Today, I still have people telling me, ‘Thank you for what you did.’”

As part of the protest, students delivered a list of demands to the administration. And while it took time and continued pressure from students and the Purdue Exponent, change came.

The Birth of the BCC

One important step was the arrival of Purdue’s first black faculty member, Helen Bass Williams. Beloved still today, Williams opened her home as a refuge for students.

“She was a trailblazer,” reflects Renee Thomas, director of the Black Cultural Center (BCC). “She provided social and cultural support that they needed. It’s always important to have people who understand your struggles and experiences, someone that you can relate to.”

Shortly after Williams arrived, the BCC opened its doors. It created a dedicated space for black students — at the time, just 1 percent of the student body — to congregate and recuperate during their days.

Although its programming and goals have expanded, the BCC remains committed to ensuring that black students have a home away from home on campus.

“In many of my classes, I was the only black student,” shares Latrice Young (LA’18). “It’s draining and damaging. If I was ever feeling like I needed to see black people or be in the vicinity of black culture, I knew the Black Cultural Center was the place to go.”

As demographics and attitudes evolve — albeit slowly at times — the cultural center has grown, too.

Widening the Circle

The current home of the BCC, the first building on campus designed by an African American architect, dates back to the late ‘90s. One of its most remarkable features is its circular entryway — a portal opening onto Third Street.

“It sends a message that Purdue is an inclusive community, and that portal is representative of leading into the black community here at Purdue University,” says Thomas. “We really pride ourselves on how welcoming we are. The Black Cultural Center is here to serve the entire campus to help educate others on the black experience, history, and culture.”

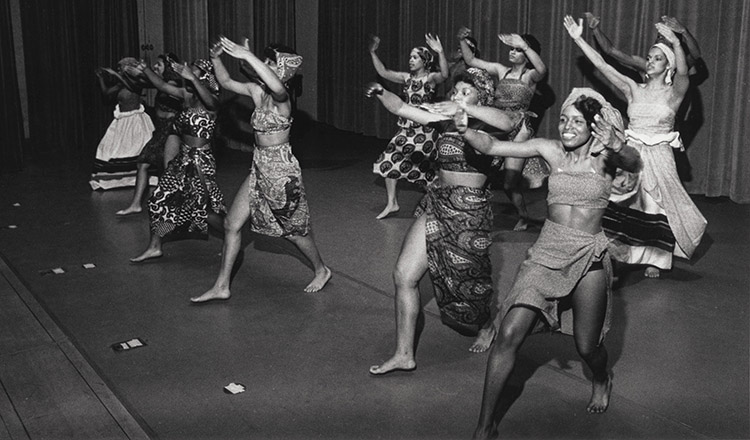

The BCC offers a public library, invites influential public figures and intellectuals to campus, and teams with other departments and organizations to bring a vibrant array of programming to Purdue’s campus.

“As a land-grant university, embracing diversity and being inclusive is vital to our missions,” Thomas says. “We bring value to campus by helping to create a climate where everyone feels welcome and can thrive.”

It’s a safe space for conversations that are difficult or uncomfortable. “I’ve met many nonblack students who had questions that they felt might offend black students,” shares Young. “The Black Cultural Center allows students to ask away. There is a place for everyone, as long as you respect the space, people, events, history, atmosphere, and structure it provides.”

Thomas believes these conversations not only are important to build better relationships and understanding on the campus but also can be a learning experience for students to understand how to interact with the broader world outside campus.

“We are becoming such a global society that Purdue is doing a disservice to our students if we don’t prepare them to become global citizens,” Thomas says. “The Black Cultural Center can play a big role in developing cultural competency, creating a training ground for students to see themselves in a broader global context. We provide space for people to test out interacting with people from backgrounds different than their own.”