Fifty years after his season of glory, the legendary football star reflects on his impact on and off the field

Leroy Keyes laughs at the question. “Did I know where Purdue was when I was back in high school? I had no idea,” he says.

Keyes (HHS’69) laughs again. It’s a big laugh, the kind that puts you at ease. The irony is thick for the 71-year-old former Boilermaker football star, a happy man who is in the autumn of life. He knows God has been good to him. On this day — like most — Keyes is filled with gratitude as he looks over his shoulder at a Purdue legacy that glows like that of few others who have walked the red-brick campus.

This gangly kid from Newport News, Virginia, who had no earthly idea where Purdue or West Lafayette, Indiana, was back in the early 1960s, grew into a strapping man who would go on to become the greatest football player in school annals and put the program on the national map while also helping shape African American relations at the University. It’s an unlikely journey that began in 1965 for a shy and scared freshman and culminated 50 years ago for a proud and confident senior who enjoyed a glorious 1968 season that still resonates today.

“Has it really been 50 years?” Keyes marvels.

Yep. Fifty years. Half a century. The mid-1960s were a black-and-white world unrecognizable in today’s high-definition era charged by a never-unplugged internet that has made the world a global village. Keyes was shaped by the roiling 1960s, which were filled with tumult and tragedy marked by the assassinations of JFK, MLK, and Bobby Kennedy. The Vietnam War raged, race riots rocked cities such as Detroit and Los Angeles, and student protests jolted leafy campuses. It was against this backdrop that legendary Boilermaker football coach Jack Mollenkopf prepared Keyes and Purdue for a 1968 season that would be one of the most memorable and greatest in school history.

“We knew we were good, but we didn’t understand how good we were,” says Keyes.

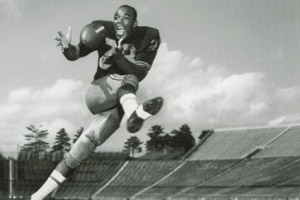

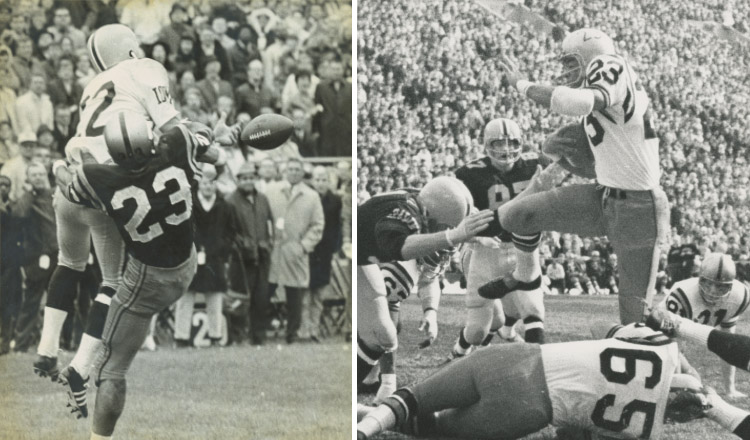

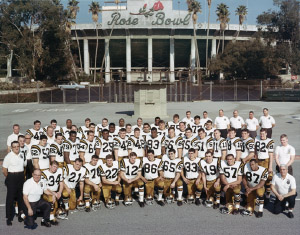

Keyes had reason to think his senior send-off season could be special. The program was in the midst of arguably its greatest run in school history. The 1966 team won the Rose Bowl behind senior quarterback Bob Griese (M’67), the Heisman Trophy runner-up that year, and Keyes, a sophomore sensation in the secondary. The 1967 season was a sweet one, too, as Keyes flipped from defensive back to flanker/halfback for his junior year. Never before has a position switch been so fruitful. When Keyes looked up at the end of the season, he had placed third in Heisman voting for a team that finished 8–2 and won a share of the Big Ten title but failed to reach a bowl when it lost the finale to Indiana.

That set the stage for a glorious 1968, one of the most anticipated seasons in school history thanks to a roster that teemed with the talent of Mike Phipps (M’70), Chuck Kyle (M’69), Tim Foley (M’70), and Perry Williams (LA’69), among others. But it was Keyes, an uncommon blend of power and speed, who was the proverbial straw that stirred the drink in West Lafayette.

“I think 1968 might have been our best team,” says Phipps. “I was a junior that year. We were pretty good in 1966, 1967, and then in 1969, my senior year. But that ’68 team was special and talented.”

Sports Illustrated thought so, too. When the season began, Keyes was plastered on the cover of the September 9 national magazine, which hailed the Boilermakers as the No. 1 team in America. Think of that for a moment: Purdue was the preseason No. 1 team in the country.

“I’m not sure we have a No. 1 team,” Mollenkopf told SI about this 13th Purdue squad.“But I don’t mind that kind of speculation. If you can’t look at a season optimistically with our talent, you can’t look at anything optimistically.”

The season began with promise. Purdue opened 3–0, including an epic 37–22 win at No. 2 Notre Dame in front of a national TV audience. “That game was a cake walk,” says Phipps. “That was a high point. We were No. 1 before we lost at Ohio State. That was a low point, but we had more high points. And Leroy was a big reason why.”

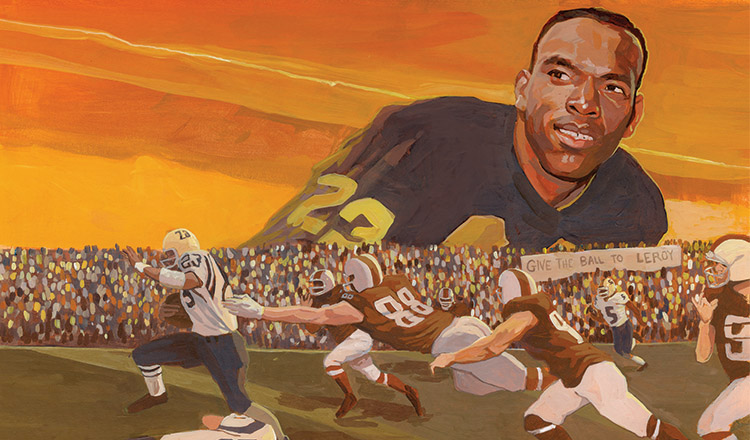

Running, catching, and even passing, Keyes could do it all. It was apparent to all that when No. 23 had the football in his hands, good things usually happened. That led to the most famous mantra in Purdue football history: “Give the ball to Leroy!”

“The one leading the chant was Coach Mollenkopf,” says Phipps. “If there was any uncertainty about the play, it was always, ‘Give the ball to Leroy!’ That was the answer. And it usually worked.”

That strategy helped the Boilermakers finish 8–2, as the angular Keyes finished runner-up in Heisman voting to USC’s O. J. Simpson. Time has done nothing to diminish the glow around Keyes. During Purdue’s centennial football season in 1987, Keyes was voted the school’s all-time greatest player. But if not for the prodding of a high school teacher, Keyes never may have landed in West Lafayette, where he still lives. He returned to campus in the mid-1990s as an assistant football coach under Jim Colletto, and then moved into an administrative role with the athletics department before retiring.

“I had a homeroom teacher in high school who encouraged me to look at Purdue,” says Keyes.

Back then, he says, the thought was if you lived in the South, you had to go north for a quality education if you were an African American.

“You weren’t going to go to the predominantly white schools in the south like UVA and William & Mary,” says Keyes. “It was how the South was set up back then. It was very segregated. We couldn’t go to certain restaurants and places because of our color. The scores and reports from our high school games were on the back page.”

Keyes’s home room teacher at Carver High kept telling him, “With your athletic and academic skills, you can go anywhere in the North.” That opportunity came when Purdue assistant Burnie Miller was tipped off about Keyes by William & Mary coach Marv Levy, who went on to fame for leading the Buffalo Bills to four consecutive Super Bowls in the 1990s. Levy wished he could take Keyes but knew he couldn’t because of the tenor of the times.

“Burnie came to watch me play and was the only white guy in the gym,” says Keyes. “It was a shock to us. Everyone thought, ‘That man must be lost.’ He visited schools I had played and asked if I was good enough to play in the Big Ten. He was told, ‘If Keyes can’t play in the Big Ten, no one in this area can.’”

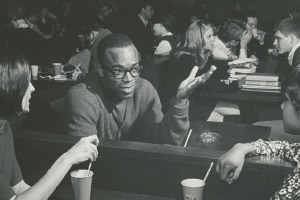

Keyes didn’t disappoint, becoming an iconic figure and part of Purdue lore. But less remembered is his work as an agent for change off the field as a participant in student protests. Purdue didn’t see the level of unrest that enveloped some campuses across the nation in the late 1960s, but there was tumult in West Lafayette tied to race relations and the Vietnam War, among other issues. And Keyes saw an opportunity to help make a difference.

Keyes was a product of his upbringing in segregated Virginia. He arrived in West Lafayette a raw, promising athlete who didn’t lack confidence and knew right from wrong thanks to a strong family.

“There was a lot of unrest in those times,” says Keyes. “There were assassinations of leaders and protests across the country and cities were burning.”

Keyes had lived through his share of discrimination and prejudice growing up in Newport News. He pushed back as a youth. And he wasn’t going to change once he arrived at Purdue.

“I was always up in somebody’s face,” says Keyes. “Coming from the South, you had a different dynamic than the kids who lived in the North. You can’t change the world through athletics. We tried.”

In the spring of 1969, Keyes took part in a peaceful sit-in in the Administration Building (now Hovde Hall) over a tuition increase. An AP photographer snapped a photo of Keyes that went across the wire.

“My uncle called and said: ‘Boy, what are you doing?’” says Keyes. “‘We didn’t send you out to Purdue to be a protester.’ I said, ‘Sometimes, you have to take a stand if something is right or wrong.’”

Keyes took another stand by taking part in a peaceful march of African American students from Lambert Fieldhouse to the Administration Building in the spring of 1968. The goal of the march: point out the lack of minority faculty members and TAs at Purdue. Minority students also wanted a place to meet and gather on campus.

The students marched single file. As they passed the under-construction pharmacy building, students picked up bricks and carried them to the Administration Building. They set the bricks on the steps and displayed a sign that read “The Fire Next Time,” the title of a popular 1963 book by James Baldwin that examined the issues African Americans had to deal with in America in the early 1960s. The march helped play a role in the development of Purdue’s Black Cultural Center which will celebrate its 50th anniversary in 2019.

“We are grateful for the role Leroy played in creating a space where students can express themselves artistically, culturally, and intellectually,” says Renee Thomas, director of the Black Cultural Center. “The BCC provides students with valuable leadership roles, broadens their experiences beyond the classroom, and prepares them to be global citizens.

“Originally established in response to black student demands for a space that reflected their culture and heritage, the BCC now stands as a pillar of inclusive excellence. We are woven into the tapestry of Purdue.”

Keyes is proud of the role he helped play at Purdue — on and off the field.

“I may not have won the Heisman, but life goes on,” says Keyes. “You don’t need a trophy to prove how great you were. How you carry yourself, how people react and respond to you is more important than a trophy in your basement.

“I think my legacy will be that I was a good guy who stood up for my beliefs. I didn’t back down from President Hovde, Jack Mollenkopf … I was gonna voice my opinion one way or another. I was always upbeat and had a smile on my face. I knew who I was and where I came from. I was proud to be Leroy Keyes.”

A Golden Era

No. 1 rankings, big wins, and top talent came to define the Purdue football program from 1966 to 1969, when the Boilermakers posted a 33–8 overall record and went 22–6 in the Big Ten under coach Jack Mollenkopf.

Purdue enhanced its Cradle of Quarterbacks persona back then with guys like Bob Griese and Mike Phipps taking snaps. But Leroy Keyes was the key cog in that era and played a vital role in helping the program to its lone Rose Bowl win after the 1966 season, finishing No. 7 in the AP poll that year.

Purdue often flirted with the Heisman in the late 1960s. Beginning in 1966, eight Boilermakers have finished 11th or better in Heisman balloting. From 1966 to 1969, the program had the Heisman runner-up three times: Griese in 1966, Keyes in 1968, and Phipps in 1969. (Keyes was third in 1967.) Phipps is the Boilermaker who came closest to winning.

“I really thought I was going to win it,” says Phipps, who lost by 154 points to Oklahoma’s Steve Owens. “They called me and Jack Mollenkopf to President Hovde’s office to take a phone call from the Heisman people. That hadn’t happened before. As I was standing there, Mr. Hovde was on the phone and I heard him say, ‘Oh, that’s too bad.’ That’s when I knew I didn’t win.”

Since then, the closest a Purdue player has come to winning college football’s biggest prize was Drew Brees, who finished third in the 2000 race. He finished fourth in 1999. Other Purdue players who have finished 11th or higher in Heisman voting: Mike Alstott was 11th in 1995; Jim Everett was sixth in 1985; Mark Herrmann was eighth in 1979 and fourth in 1980; and Otis Armstrong was eighth in 1972.

“It’s a heck of an award,” says Keyes, who was the No. 3 pick in the 1969 NFL draft. “It would have been fun to have won it. But it just wasn’t meant to be.”