Machine vision’s new niche — sorting baseball cards

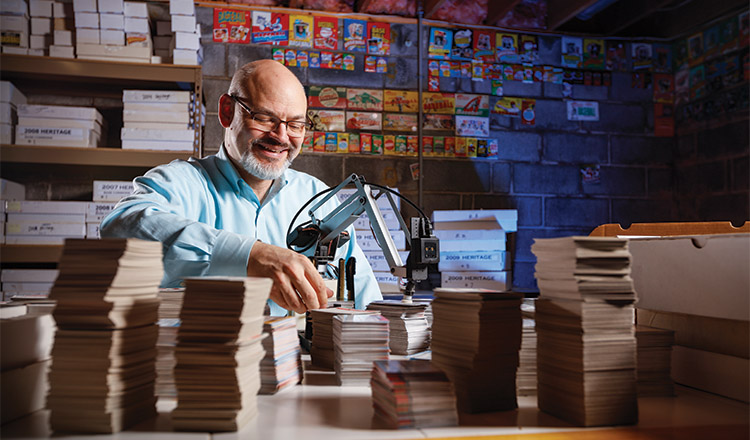

By day, Jim Parker (ECE’90) designs and engineers tiny machine vision cameras embedded in surgical and lab equipment. At night, he uses the same technology in his side business sorting baseball cards.

Yes, baseball cards.

Parker works for Syracuse, New York-based JADAK, a top supplier of data collection technologies to the medical device and life sciences industries. He led the five-person R&D team that created the company’s Clarity 2.0 software, which lets a user customize machine vision algorithms for specific tasks.

“It provides a simple drag-and-drop graphic user interface,” Parker says. “I used it to find the numbers within the circle on the upper right portion of the card back.”

He’s done more than that. Parker modified a mechanical robot arm he bought online with a 3-D-printed fixture to hold a small camera equipped with the Clarity software. The robot’s one-by-one-inch footprint is small enough to clamp to a table for presorting cards that Parker sells direct to repeat customers and on eBay.

The 50-year-old Parker spent his first decade after school at medical products maker Welch Allyn in Syracuse. In 2000, he was just the third employee hired at JADAK, which now has more than 200 employees. The company was acquired by Novanta, based in Bedford, Massachusetts, in 2014.

Parker rediscovered card collecting 15 years ago. He focuses on Topps Heritage cards favored by older collectors with deep pockets. The sub-brand debuted in 2001 mimicking the design of Topps’ first baseball card set from 1952. The twist was the cards pictured then-current Major Leaguers. This year’s Series I issue depicts 500 of today’s players in the 1969 design.

Parker makes money from nostalgia buffs who want to own sets without investing the time and effort to create them. His niche is filling requests from set builders missing certain cards. But his biggest profit comes from flipping serial-numbered rarities inserted in the thousands of packs he opens annually. He uses his proceeds to buy large collections he learns about from others in the hobby. That keeps his 250,000-card inventory fresh and fosters repeat business.

Before he created his unnamed robot, Parker found sorting cards more relaxing than tedious. Sometimes his father, Andrew (T’63), would help. Parker and his wife, Tamra, have three sons. Only the youngest, 10-year-old Jakob, is interested in his father’s business — possibly because he gets to keep 10 percent of the profit from cards he prepares for sale on eBay.

The four-axis parallel-mechanism robot arm is modeled after the ABB industrial PalletPack robot. Its Chinese maker, uArm, pitched it as capable of dealing Black Jack. Parker thinks it gives him an edge in his card game. When 16 cases of 2018 Heritage (about 40,000 cards) arrived this spring, he placed about 300 low-value base cards in the robot’s hopper and flipped a switch. It hummed along, lifting, reading, and placing a card on a preset stack every three seconds. Parker set up a two-step process for the robot to sort by 100s and then by 10s. Then it stopped working.

“One of the servo motors went bad, so I had to sort by hand for about a week, which was rough,” Parker says. “I got new parts and repaired the robot, and now it is up and running smoothly again.” After some mechanical tweaks, he increased its sorting speed. About 60 percent of the sets he’s assembled this year involved some automation.

Parker’s IT expertise could not overcome quirks in the current card design. “One tough part is that the numbers this year are much smaller than in previous years. So, the camera resolution limits the effectiveness and accuracy of the number detection algorithm.”

Programming the camera to look where most identifying numbers appear is easy enough. Some 20 percent, however, have numbers elsewhere on the card. Parker could program for that, but it’s easier to have the robot drop them into a separate pile for hand sorting later.

His current robot arm can sort into 12 stacks, enough to handle each 10-digit group with a discard pile. It is accurate to half an inch and occasionally misses its target. An upgraded robot from uArm touts accuracy within two millimeters but costs more than twice the $300 Parker spent.

His card business consumes about 10 hours a week. But thoughts of what a better robot and software could do come at random times. “Ideally, I could put a stack of cards in, and it would build the piles one by one, and I could build the set.”

When he posted a YouTube video of his robot on hobby sites last year, the reaction blew him away. Along with “I want one!” emails came ideas for improvement. For example, Parker now centers the guides that pick up the card to reduce the chance of damage when it is dropped onto a pile.

No cards have been harmed so far, but the robot “is not really consumer-friendly yet.” That’s OK since Parker doesn’t plan to make them for sale anyway.

He says he could create a process to grab, read, and sort cards from a 3,200-count monster box and automate the set-building process — but not anytime soon.

“I am happy with where it is right now. It is doing the job I want it to do,” Parker says. “I find it funny that Topps does all this work to randomize these cards, and we spend all this time to unrandomize them.”