The following story appeared in the Summer 2017 issue of Purdue Alumnus

Holocaust survivor found his passion, sense of belonging in Purdue sports

As a Jewish Latvian teenager, Mickey Kor (P’52) obsessed over death. That outlook, not the product of angst or adolescent depression, bore straight out of the reality of life in a Nazi concentration camp, his enslaved reality from the age of 13 to 17. Beatings, forced labor, and murder were commonplace, with little guarantee of seeing next week. He survived, however, and later even thrived as a pharmacist and family man. Thanks to a big assist from a US Army lieutenant colonel and perhaps the escapism provided by Purdue sports.

Kor has told the story of a Nazi guard spewing his disgust for Jews in their meager barracks. Beneath his breath—because anything audible would have led to at least a beating—Kor said, “I’m not too crazy about you either.” Yet the whispered resistance sounded like a full choir in his soul. Or something like the ear-splitting decibels that would accompany a buzzer beater in a packed fieldhouse.

Escaping a “death march” as a 17-year-old, Kor hid out in a building until the 250th Engineer Combat Battalion, Seventh Army, found him. Mickey wore American soldiers’ leather jackets and discovered Coca Cola. Sponsored by Lt. Col. Andrew Nehf, he moved to Terre Haute, Indiana, a home he never strayed too far from over the next 70 years. Before attending Purdue, Kor took a gym class at Indiana State taught by Johnny Wooden (AAE’55), with whom he maintained a longtime letter correspondence.

Kor met his wife Eva on a trip to Israel in the late 1950s. A Holocaust survivor herself, Eva Mozes and her twin sister Miriam had been subjected to the medical experiments of Josef Mengele at Auschwitz. Eva’s parents and two older sisters, all abducted from a Romanian village, were separated from the twins and murdered in the gas chambers. Just 10 years old then, Eva and Miriam relied on each other for survival.

A fiercely independent adult, Eva describes her courtship with Mickey as less romantic and more a matter of negotiation. Not speaking the same language, they had to dip in and out of translation dictionaries to understand each other. Before leaving Israel, Mickey asked Eva to marry him—a take-it-or-leave-it proposal, as he planned to return to Indiana.

Eva’s story is better known than Mickey’s, even though she would have been content to not share it with anyone. In negotiating a strange land, even acts of Halloween trickery by neighborhood kids could trigger awful memories of harassment at the hands of Nazis.

“I had a difficult time in the United States. I was a sergeant major in the Israeli Army and became a sergeant major in diaper changing,” says Eva, who soon had two kids, Alex and Rina. “And the only thing Terre Haute and Tel Aviv have in common is that they start with a T.”

In 1984, Eva founded CANDLES, which stands for Children of Auschwitz Nazi Deadly Lab Experiments Survivors. The mission: to locate as many as possible of the 1,500 sets of the tortured “Mengele twins.” To date, they’ve found 122 individuals from 10 countries. The CANDLES Museum, opened in 1995, was torched to the ground by an arsonist in 2003 and later rebuilt. Today it stands as a testament to remembrance and forgiveness as Indiana’s only Holocaust museum.

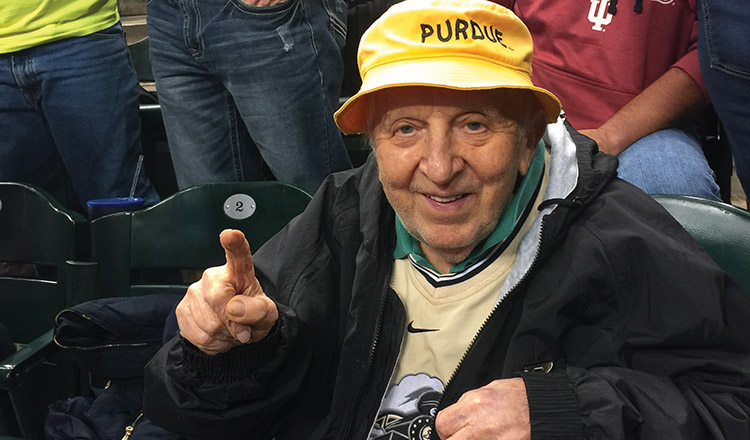

Eva became an international spokesperson, eventually forgiving her Nazi captors, and has earned some of the state’s highest honors from three consecutive Indiana governors, including Purdue University President Mitch Daniels. Mickey, on the other hand, while occasionally holding court as a museum docent, found ways of mitigating old memories. He poured himself into fandom, a Purdue football and basketball season ticketholder since the mid-1990s, often recruiting two friends to drive to West Lafayette.

“Mickey was treated worse than an animal in his formative years,” Eva says. “Focusing on Purdue basketball and football was not only entertaining, but everybody was equal there. He finally belonged to his group.”

Mickey passed his passion for Purdue onto his son. “People who know me and meet my dad know where I got my love of sports,” says Alex Kor (MS HHS’84), who attended Butler University on a tennis scholarship before earning a Purdue graduate degree. “I think he’d admit it’s an escape from his past. But he really seems to live and die with Purdue basketball.”

With Mickey on the brink of death last summer, their daughter, Rina Kor (AAE’86), left her job in San Francisco to help nurse him back to health. In addition to changing medicines that helped to improve his dementia, Rina administered good television doses of Donald Trump and Purdue basketball (he’s a fan of both) through the end of the late fall. “His mental health is now better than it was five years ago,” Eva says. “That’s mostly due to our daughter Rina.”

There’s no “one-size-fits-all strategy” for surviving such a violent ostracism from society, says Kip Williams, professor of psychological sciences. “Where Eva may have found a project to immerse herself in, Mickey found a group to which he felt a close bond. There are many routes to recovery.”

There are many reasons for sharing stories from such unspeakable acts in human history. Sarah Powley (MS EDU’85), an instructional coach for secondary school teachers, knows the importance of lessons learned. The co-chair of the April 2017 Greater Lafayette Holocaust Remembrance Conference, Powley says, “We see remarkable courage and amazing resilience in the Kors’ stories. Eva and Mickey are models for all of us.”