Reading literature boosts empathy among other health benefits

Quick: name the last book you read! If you’re struggling, you’re not alone. According to a report from the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, Americans are devoting less time to reading for pleasure with every passing year — in 2017, the average amount of time spent was just under 17 minutes per day.

It’s a trend that Manushag (Nush) Powell, director of graduate studies in English, would love to see reversed. Reading in general is a valuable pursuit, she asserts, but reading literature can make you a better person. “In the almost 20 years I’ve been teaching literature at the college level, I’ve seen the difference that reading fiction can make to people — young, old, veterans, nontraditional students — the activity benefits everyone. It increases empathy, enhances social skills, and helps you to understand yourself and others.”

Literature is also beneficial to brain health because it requires deep reading, a slow, careful parsing of the text rather than a cursory skim, Powell continues. “The slow and careful reading that literature demands stimulates blood flow to different areas of the brain,” she explains, “thereby increasing neuroplasticity and improving memory function. It may even help stave off Alzheimer’s and dementia.”

Powell’s observations are hardly anecdotal; neurocognitive research backs her assertions: “In 2012, literary scholar Natalie Phillips partnered with researchers in Stanford’s neuroscience department to perform MRIs on subjects while they read excerpts of a Jane Austen novel,” Powell says. “She discovered that reading for pleasure stimulated some areas of the brain, while close reading activated multiple cognitive functions.” In other words, not all reading is equal.

The benefits of reading fiction are also distinct from reading nonfiction, Powell continues: “Reading fiction encourages one to expand social capacity and enhances theory of mind — the ability to understand and appreciate perspectives different from our own. Reading nonfiction doesn’t expand soft skills such as cognitive empathy in the same way.” Reading fictional narrative also improves one’s ability to recognize patterns and discern meaning from structure, she asserts. “I’ve seen it in my own classroom. People who dwell happily in the world of possibilities that fiction evokes tend to perform better. Some of my strongest students are STEM students who are also avid readers of fiction — they’re fantastic!”

Although many view reading literature as a guilty pleasure, Powell contends it’s more accurate to characterize it as an act of rebellion or social conscience. “To participate in deep reading, you must carve out time to focus on the text, and in today’s busy world, that’s an act of rebellion because it forces you to push back on other demands on your time,” she observes. There’s also a prevailing sentiment that our society is losing is capacity for empathy, Powell notes. “It’s been shown that reading literature increases one’s ability to empathize, so if you’re reading thoughtfully, you’re engaging in a social action that contributes to the greater good.”

Then there are the benefits to one’s own health and well-being. “Reading literature allows one to claw back against the dehumanizing effects of the constant reading we do on the internet,” says Powell, “and if you have books in your home and your kids see you reading, you’re modeling healthy behavior.” Reading a book before bed also promotes better sleep. “When you read, you feel calmer and happier, and that’s conducive to rest,” says Powell.

It’s also preferable to grab an actual book rather than a digital facsimile, Powell notes. “I’m just as guilty as the next person — I use a Kindle from time to time for sheer convenience — but reading on a computer doesn’t convey the same benefits.” Powell says she has witnessed the difference with her students. “I’ve done experiments in which I’ve had students read something online rather than from a book, and their retention just isn’t as good. There’s something about engaging multiple neural pathways — seeing the book, holding the book, even smelling the book — that seems to have an effect on the way that memories get made.”

In the end, however, Powell concedes that the most important thing is to get people reading, no matter what the subject or means of delivery. And in that regard, she is encouraged by what she sees. “Despite cries that literature is dead, there are areas of fiction that are expanding: young adult and crossover fiction (works that appeal to teens and adults alike) spring to mind.” People are discovering that reading fiction helps with emotional stability and health, says Powell, and they are embracing it. “It’s a choice you have to make, but it’s a choice with obvious benefits,” she observes.

Pressed to recommend one or two books that might get a new or lapsed fiction reader into the groove, Powell declines. People should read whatever works for them, she asserts. “The main thing is to read, whether by joining a book club, a library group, or some other community of readers.” For example, Powell points out, the English department leads a Big Read every year in which the University focuses on a specific book — it’s taught in classes; professors do community lectures on related topics; and the school partners with community libraries. This broad-spectrum approach offers people a host of ways to access the material and rediscover the joy of reading, she observes.

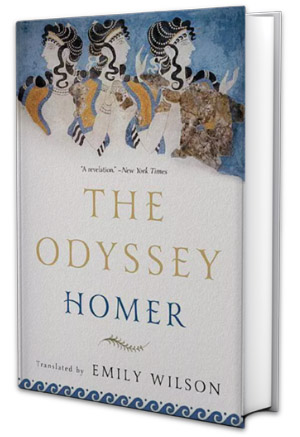

“This year we’re reading Emily Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey,” says Powell. “It’s beautiful and shockingly accessible — if you only have time to read one book this year, I would highly recommend it.” The book offers a powerful demonstration of the way in which reading fiction cultivates empathy, she notes. “Reading this classic text in the 21st century shows people that they can mentally place themselves in a profoundly alien culture and still make connections with the characters.” In the end, however, if people are reading, Powell doesn’t much care what they choose. “Any reading is good reading,” she says.