When Tamara Markey (IE’94, MS’16) walked down the halls of her Indiana high school, McKenzie Center for Innovation and Technology, one day in October, she thought she was heading to a meeting for one of the many programs she leads.

But then she turned the corner and saw her husband, Maurice (IE’98), and her children, Myles, Hannah, and Gabriel, sitting there amid a huge crowd — all of whom burst into applause when they saw Markey, as she had been named the 2019 Indiana Teacher of the Year.

She had known she was one of three finalists, but to receive the honor at the surprise ceremony “completely caught me off guard,” says Markey, who teaches engineering at the high school. “To see most of the school gathered there, with my colleagues and my family, was so humbling. Months later I continue to question, ‘Why me?’”

But for anyone who knows Markey, the answer is clear: She serves her students not only through teaching but a variety of other projects. She’s a member of the district’s STEM Coalition Task Force; a faculty adviser for the architecture, construction, and engineering mentoring program; creator of the Girls In Technology mentorship initiative; and a member of the Graduation Pathways committee.

In short, Markey is “a member of Team Too Much” — a badge she mentioned proudly in her impromptu acceptance speech at the Teacher of the Year ceremony. “I have a personal rule that I don’t like to complain,” she says. “If I find myself complaining, I have to either do something about it or shut up. Everything I’ve done has been fueled by that rule.”

Those efforts include Markey’s founding last year of the Girls In Technology mentorship program, which was inspired by dispiriting experiences in the gender makeup of her engineering classes. “I have taught classes that included only one girl student,” she says. “Engineering doesn’t look that much different than it did when I was in school decades ago. That’s something I don’t just want to complain about. We can start making change within the classroom.”

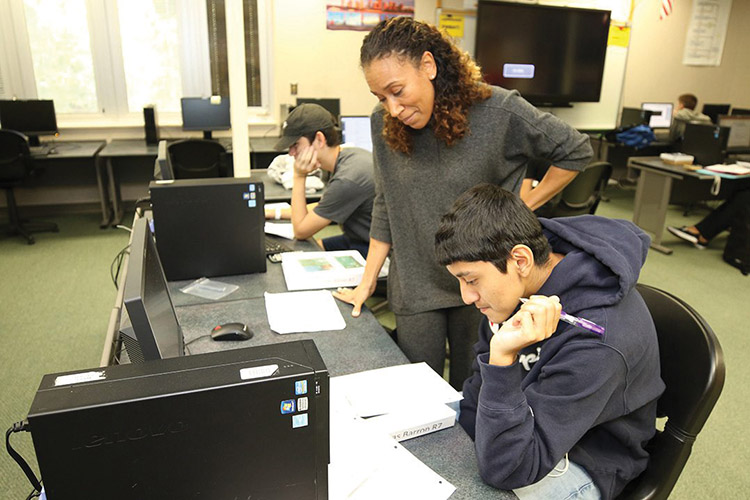

Markey’s engineering courses are part of Project Lead the Way, a nationwide program with a mission to “create a transformative learning environment and empower students to develop in-demand knowledge and skills necessary to thrive in an evolving world.”

Markey says she takes that mission seriously. “As our world grows in terms of technology, it’s clearer and clearer that what I teach is very important. There is no aspect of our lives that technology does not touch.”

As a teacher of an elective course, Markey says she appreciates that she “has some more freedom than teachers of core curriculum. I can have a bit more of a relaxed approach because I’m not pressured to teach to a test.”

But Markey has also learned to shift her approach to teaching engineering since starting her career at McKenzie in 2015. Her courses include students from two high schools, and the combined group comes from widely varied socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds. “I learned very quickly my first year that I have students across the spectrum of academic ability,” Markey says. “I couldn’t just get in front of the classroom and assume that everyone was starting from the same point or that I could grab everyone’s attention in the same way.”

Nor could she necessarily expect the same outcomes for each student, she adds. “When a kid comes to class and I see that he’s not engaged day after day, I can’t just write him off as a slacker and a loser. I need to understand that my students are potentially dealing with important life issues outside the classroom, and as a teacher, it’s my responsibility to help him get the resources he needs.”

Before joining McKenzie, Markey began her teaching career at Fall Creek Valley Middle School in Lawrence Township, Indiana — 12 years after taking a career break to raise her three children. Prior to teaching, Markey worked as an engineer at Amoco Oil and BP Pipelines. But all throughout her time at Purdue and her career as an engineer, Markey suspected deep down that she was destined to teach.

“The job of a teacher is so much more than curriculum; it’s a profession of the heart,” Markey says. “There’s no way you can do it adequately without learning about — and serving — the whole person.”